With Rustom Racing Beyond The Finish Line, Are Biopics Re-Emerging As A Bollywood Favourite?

Why is Commander Nanavati the new hero that every star wants to play?

On the face of it, two films on the same topic might seem like a coincidence but at times there are more things at play.

Although it’s the trickiest of genres in Hindi cinema, the biopic is fast becoming the go-to variety for mainstream stars.

The recent success of Rustom, a film based on the landmark Nanavati trial, ought to have quelled the ambition of anyone else considering making a film on the same subject but the opposite has happened. As Rustom raced past the 100 crore mark, news of two more films on the same subject— one an Aamir Khan production and the other, tentatively titled “Love Affair”, to be directed by Pooja Bhatt— became public.

Later this year, Aamir Khan’s Dangal— directed by Nitesh Tiwari— would become the second film within a year on wrestling after Salman Khan’s Sultan (2016) and this phenomenon of “twin films”— two or more films with the same or very similar plots, produced or released at the same time by two different studios or producers— is more common than one would like to believe.

Dangal, Sultan, Rustom, Love Affair or the untitled Aamir Khan project are not the first handful of films on the same topic that would release around the same time. The most common example of twin films in Hindi cinema is the phase where a single year, 2002, witnessed three films on Bhagat Singh— 23rd March 1931: Shaheed (2002), The Legend of Bhagat Singh (2002) and Shaheed-E-Azam (2002).

If that wasn’t enough, a few years later, Rang De Basanti (2006) also had a sub-plot of the revolutionary’s life where the actor Siddharth played Shaheed-e-Azam Bhagat Singh. Amongst all the films that tried to capture Bhagat Singh’s life and heroism, the one directed by Raj Kumar Santoshi— The Legend of Bhagat Singh— has stood the test of time. Even though it doesn’t fully explore aspects of the martyr’s brilliant defense in court or his opposition to the caste system, it’s better recalled than the other two.

On the face of it, two films on the same topic might seem like a coincidence but at times there are more things at play. Usually, a topic becomes popular and ends up inspiring more than one script that leads to a race between two parties to get their film out earlier but some have attributed the concept of twin films to a kind of industrial espionage.

While both the Bhagat Singh films and the wrestling films seem to be a result of a zeitgeist of their times, the interest in the Nanavati case, as a subject, appears to be far deeper. The last case of jury trial in India, the Nanavati trail shook the foundation of the Indian judiciary when the judge in the case refused to accept the jury’s verdict.

In 1959, Commander Kawas Manekshaw Nanavati, a highly decorated Naval Commander, was tried for the murder of Prem Ahuja— his wife Sylvia’s lover— and even though he had surrendered to the nearest police station after confronting Ahuja in a closed room, the jury declared him “not guilty.

Following the dismissal of the jury’s verdict by the Bombay High Court, the case was retried as a bench trial but by then there was enough media buzz. The crime of passion evoked extreme reactions in people and even the press— mainly the tabloid Blitz run by R. K. Karanjia, a Parsi himself. He ran exclusive cover stories, openly supporting Nanavati by portraying him as a wronged husband and an upright officer, betrayed by a close friend, Ahuja. The deceased’s playboy image was compared to the Commander’s ideals. The fact that there were “Ahuja towels” and “Nanavati Revolvers” being sold on the streets or that a single copy of Blitz, which was priced at 25 paise, was selling for two rupees, gives the idea of just how pumped the environment might have been.

The manner in which the events of the whole case unfolded is the kind of story films are made of. Add to that the abolishment of jury trials in India and the Commander being pardoned after he spent three years in prison, too, is the stuff of great cinema. The case has been cinematically adapted twice before Rustom namely Yeh Raaste Hai Pyar Ke (1963) and Gulzar’s Achanak (1973) that featured Sunil Dutt and Vinod Khanna as the Nanavati inspired characters, respectively.

Interestingly enough, in her autobiography, Leela Naidu— who played the character of Sylvia in Yeh Rastey Hai Pyar Ke— mentioned that the script was written before the Nanavati case and it’s just a happenstance that the “reel” and “real” ended up resembling each other. But, even with three cinematic adaptions, the intricacies of the case have not made it to the screen in a manner that would do justice to them.

Nanavati was said to move around in the same circles as the then Prime Minister Nehru and he was someone that Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, had personally recommended on many occasions. But to say that Nanavati’s influence won him a pardon would not be totally correct. The massive public sympathy for him as well as the jury’s decision, that was aided by Blitz, reveals that there was enough for the then Governor of Maharashtra, Ms Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, to officially pardon Nanavati. Moreover, by the time the entire case ultimately came to a pass, it had also become a kind of a standoff between the Parsi and Sindhi communities. The Parsis held rallies across Bombay and the Sindhi community supported Mamie Ahuja, Prem’s sister. Even the lawyers Ram Jethmalani, who led the prosecution, and Karl Khandavala who represented Nanavati, were clearly divided.

In a newspaper report following the release of Rustom, Aamir Khan’s production team is quoted to have said that their version was aiming to focus more on the details of the trial rather than what led to it. Rustom briefly hints at the Parsi-Sindhi divide during the trial but critics believe that the film’s narrative squandered a great opportunity to transcend beyond the usual. Khan’s version was supposed to have been helmed by Ram Madhvani, who brought to life the real-life story of air-hostess Neerja Bhanot in this year’s Neerja (2016). Apparently, it also had Nanavati’s widow, Sylvia, as a consultant.

While not much is known about the Pooja Bhatt version but if the title “Love Affair” is anything to go by, then it would be more about the betrayal of trust between the husband and wife.

So, what is it about the Nanavati case that evokes such passion across decades?Moreover, how is it that a real-life incident that took place in the late 1950s seems more relevant today than ever before?

The answer lies in the way television news holds trials every single evening and beams it into the homes of millions of ordinary people.

A Rustom/Nanavati becomes appropriate in this day and age because of the manner in which every news show creates a two-way communication between those being tried and the viewer. The channel invites viewers to participate, allows them to have a say, urges them to express an opinion and empowers them to pass a verdict of sorts by the click of a button. In the same manner, the jury aspect of the Nanavati case is what makes it a fascinating tale that no writer could have conjured up. It is for this very reason that the element of the jury and the opportunity to explore human fallacy across a spectrum makes it the most enticing feature when one thinks of a film on the Nanavati trial.

Does the jury’s decision to not find Nanavati guilty also suggest that it was a better system than the one that we have now? And, considering that our legal system is reformative and not punitive, does the not guilty verdict somewhere fulfill the dictum of “culpae poenae par esto” or “let the punishment fit the crime”?

One of the biggest challenges for any film to interpret would be to overcome an acute sense of presentism in the manner in which the jury along with the common man on the streets responded to the Nanavati trial. The tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values burdens deciphering Nanavati’s motivation or, for that matter, Sylvia or Prem Ahuja’s.

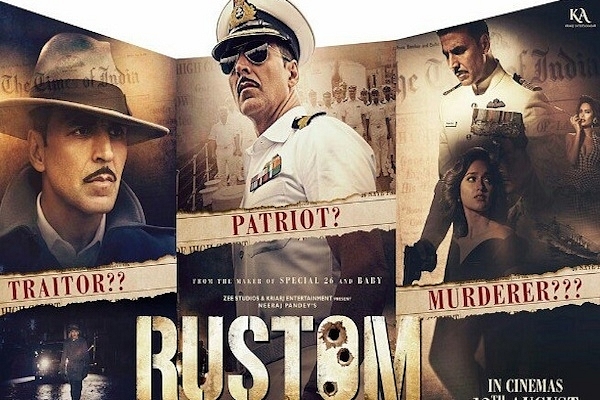

A tagline on Rustom’s poster— “Patriot? Traitor?? Murderer???”— raises the question that the murder committed by Rustom Parvi (Akshay Kumar) could be linked to his patriotism as he was a Naval officer. Can Rustom’s ingrained patriotism momentarily leave his body when he supposedly kills his wife Cynthia’s (Ileana D’Cruz) lover Vikram Makhija (Arjan Bajwa)? Or is it that Rustom’s patriotism might have played on the jury’s mind while pronouncing the not- guilty verdict? Is it completely impossible to assume that Rustom feels let down by his wife Cynthia’s transgression? Unfortunately, in Rustom’s case, an inescapable presentism works on both sides. The filmmaker and the critics both seem compelled to attach what we feel today to a story based on an event that took place six decades ago.

The further intricacies of Nanavati’s pardon such as how it was supposedly delayed for the fear of an angry response from the Sindhi community; or the day Nanavati was pardoned, Bhai Pratap— a Sindhi trader serving a sentence— was exonerated too or how Mamie Ahuja gave her consent in writing to pardon Nanavati would also add to a compelling screenplay. Perhaps this is why there could be more to a film based on the Nanavati trial even after Rustom has long crossed the finishing line.