As Pakistan Threatens Nuclear Crisis Over Citizenship Law, A Look At Its Betrayal Of Bihari Loyalists After 1971 War

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan said on Tuesday (18 December) that the abrogation of the special status of Kashmir and forging a new citizenship law could lead to millions of Muslims fleeing India, creating "a refugee crisis that would dwarf other crises".

Khan was addressing the Global Forum on Refugees in Geneva, Switzerland.

"We are worried there not only could be a refugee crisis, we are worried it could lead to a conflict between two nuclear-armed countries", said Khan. Khan also categorically stated that Pakistan wouldn’t accept any Muslims from India.

The above statement of Imran Khan is controversial for many reasons.

First, the Citizenship Amendment Bill is not about Indian Muslims, or any Indian community, but only immigrants. There is no question of ‘accepting Muslims from India’.

Secondly, Pakistan movement was itself the cause of the biggest refugee crisis in the post-World War II world and was spearheaded by the Muslims from north Indian heartland - now these have become unacceptable for Pakistan.

Even after Muslim League exhorted Muslims to leave India for the promised land of Pakistan “embodying the essential principles of Islam”, more Muslims stayed in India than leave for Pakistan. And those who did leave - the ‘Mohajirs’ - faced discrimination from locals.

In a letter published in Dawn on 18th January, 1948, a newly arrived Indian Mohajir wrote:

"I feel it is the struggle and sacrifices of people like us that went a long way towards the realization of Pakistan. Or is it that we were cleverly duped and Pakistan was meant for the people of Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan, Bengal and Frontier, and not for every Musalman of India?"

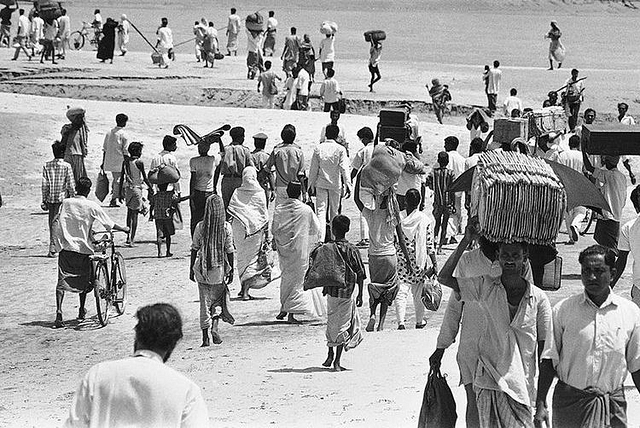

Despite being a country formed on the promise of Muslim homeland in the Indian subcontinent, Pakistan didn’t accept stranded Pakistanis in Bangladesh - mostly Urdu-speaking Muslims of Bihari-origin - who had sided with West Pakistan during the Bangladesh liberation war.

The genocide committed by the Pakistan in East Bengal (now Bangladesh) engulfed Bengali nationalists as well as minority groups like Hindus. A fatwa was issued in Pakistan that Bengali nationalists were ‘Hindus’ and therefore, it was justified under Islamic law, to capture their women as the “booty of the war”.

Bangladeshi nationalism was termed as an ‘Indo-Zionist conspiracy’, and Hindus were especially targeted. Their houses were burnt down, temples destroyed, women were raped, tortured and they were killed en masse. The intelligentsia was targeted and systematically wiped out.

The massacres were carried out by Al-Shams and Al-Badr forces on the instruction of the Pakistani Army. These forces contained significant numbers of Urdu speaking Bihari Muslim population (called Mohajirs in Pakistan). The latter was largely composed of Biharis.

The Bihari Muslims also claim that they were targeted by the Bengali Muslims and lost lives in significant numbers in the violence.

The Bihari population in Bangladesh was predominantly pro-Pakistan, and after the formation of independent Bangladesh, wished to be repatriated to Pakistan. According to Partha Ghosh, around 70 per cent of the Bihari Muslims in Bangladesh opted to go to Pakistan, despite Supreme Court of Bangladesh offering them citizenship in 1972.

Several Pakistanis, especially the Muhajir community, demanded the Pakistani government bring back the Bihari Muslims - the Mohajir Quami Movement (MQM) being the most enthusiastic supporter of Bihari settlement in Pakistan. The issue also created strife between Mohajirs and other communities in Pakistan.

Initially, Pakistan accepted around 1,70,000 Biharis, but latter stopped, despite monetary support from the Organisation of Islamic Countries, World Muslim League and others international organisations, making these Bihari Muslims "stranded Pakistanis" with no citizenship.

In 2002, Pakistan president Pervez Musharraf said he sympathised with the plight of the Biharis but could not allow them to emigrate to Pakistan.

Interestingly, while the stranded Pakistani awaited in crowded and undeveloped refugee camps-cum-slums in Bangladesh to be sent to Pakistan where their loyalty lay, the repatriated ones faced similar poverty and discrimination from the local Pakistani population, an example being the 1980s Karachi riots.

Hindu persecution and oppression of Muslim minorities

In Pakistan, the legacy of Hindu-hatred runs so deep that also any group - even those that come under the Muslim fold - that seems to be straying away from the path of authentic Islam is labelled as ‘Hindu’ or ‘Hindu-friendly’ so as to justify their killings as they are kaffirs.

The relations between different Islamic sects, Sunnis, Shias, Ahmedis, Sufis etc, with different interpretations and observance of Islamic texts, practices etc are an internal matters of Islam, with India or any other country having no authority to preside over.

The nations which have declared themselves as Islamic also consider it unwarranted for other ‘secular’ countries to interfere in the internal matters of Islam - especially those with majority non-Muslim population like India.

This is where the difference between Hindu persecution and atrocities against Muslim minority groups in Islamic countries becomes important. Hindus are persecuted in the name of religious injunctions that they have absolutely no participation in or association with, and therefore, can do nothing about.

The crimes against Hindus are a part of the historical hatred against polytheists, with the aggression being largely one-sided. Here’s where one needs to distinguish religious persecution from communalism or majoritarianism.

Most of the post-colonial nations suffer from the challenges of inter-communal strife. Communalism is based on various factors, including non-religious ones, like the distribution of scarce resources, political power etc. The crimes against Ahmadis, Shias, and other Muslim minorities in Pakistan is more an example of communalism or sectarianism within Islam, rather than religious persecution.

On the other hand, the Indic minorities like Hindus, Sikhs, etc don’t have a seat at all on the table on which different Muslims groups sit, interact and negotiate their space, sometimes violently, other times not.

This dynamic is manifested in the unity of different Muslim communities in Hindu-hatred. If Hindus and minority Muslim groups had a shared experience of persecution at the hands of the majority Sunni community, one would expect solidarity and shared expression of resistance, which is not the case at all.

In fact, quite the opposite, the different Islamic groups try to prove their superiority by claiming to be the farthest from their ‘idol-worshipping’ Hindu past and closest to the pure Islam of the Middle East, and glorify historical figures of their community for their significant contribution to ‘Ghazwa-e-Hind’.

One shouldn’t commit the fallacy of hyphenating the hatred against Indic communities and crime against Muslim minorities in Pakistan, because the latter is irrelevant to the former.

The relation between different Muslim sects are irrelevant to the Hindu persecution, which would happen either way, whether under the influence of a Sunni ruler Aurangzeb in Delhi, or a Shia missionary Shams-ud-Din Iraqi in Kashmir.

India or any modern nation state cannot resolve the issue whether Ali was the rightful successor of Muhammad or Abu-Bakr, whether Ahmedis can still be Muslims even after accepting another prophet after Muhammad (rejecting latter’s finality), and whether praying to the Sufi saints constitutes shirk. India cannot decide for the Pakistanis whether they want to live in an Islamic nation or not.

What India can do is provide shelter to the people who have nothing to do with Islam yet have been persecuted in its name for centuries.