As Sedition Charges Are Dropped Against 49 ‘Eminent Intellectuals’, Here Is All About The British Raj Law

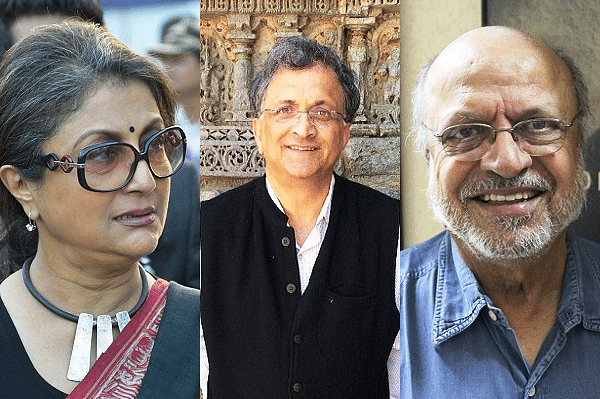

In July this year, forty-nine celebrities, including actor and film-maker Aparna Sen, author Ramachandra Guha and film-maker Shyam Benegal wrote an open letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi raising concerns about mob lynching and other issues.

The letter generated criticism for being biased, ideologically motivated and one-sided.

A Muzaffarpur-based advocate Sudhir Kumar Ojha filed a PIL against the 49 celebrities for the letter. On 3 October (Thursday), a sedition case was registered against the celebrities on the local CJM (chief Judicial Magistrate) court's order.

The move was criticised by scholars and activists.

"I heard about this in total disbelief because I cannot imagine any court admitting a case of sedition against that letter," eminent film-make Adoor Gopalakrishnan was quoted as saying by NDTV.

"When someone criticises the government it is not sedition. We are living in a democracy," he added.

Today (10 October), the Bihar police decided to drop the sedition case describing it as ‘maliciously false’, and also stated that a case will be filed against the petitioner for filing frivolous complaints.

What is sedition?

‘Sedition’ is included as a punishable offence in Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code. The section defines sedition as the attempts to bring into “hatred or contempt”, or attempts to “excite disaffection towards, the Government established by law”.

The section was included in the Indian Penal Code by the British in 1870 who were concerned with the Wahhabi activities of Muslim preachers against the Raj.

The section incorporates a broad area of activities- “by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise” that can be seditious. Also, there is no need to demonstrate actual harm caused by the speaker but an “attempt” is enough.

The section clarifies that “disaffection” includes disloyalty and all feelings of enmity. It further states that “disapprobation”of any government policy or action, and seeking its alteration by lawful means “without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection” are not an offence under the section.

History of usage in British Raj

Section 124A has been notorious for its usage against the nationalist voices in the Raj. Since its incorporation in 1870 in the IPC, the sectioned was broadened in interpretation to include all hues of nationalist activities.

The first known case was against Jogendra Chunder Bose, who in his article, published in his own Bengali magazine Bangobasi, criticised the government’s Age of Consent Act, calling it ‘forced Europeanisation’ of the Indians. However, the article disavowed rebellion saying that Hindus were incapable of it.

The Chief Justice presiding over the case argued that though Bose didn’t call openly for rebellion, his words were calculated to create in the minds of reader a disposition not to obey the government.

In 1897, Bal Gangadhar Tilak was tried on sedition charges for his lectures and patriotic songs at the Shivaji Coronation Ceremony. Tilak’s speeches also didn’t make any direct reference to overthrowing of the government.

This time, the sedition clause was interpreted broadly to include “any writing that was found to be attributing every sort of evil and misfortune suffered by people, or dwelling on its foreign origin and character, or accusing it of hostility or indifference to the welfare of the people.”

Few months after this in Prathod case, the sedition was expanded to include basically any speech or action that attempted to persuade Indians not to love the British rulers.

The above two cases led to an amendment in the Section 124A by the Raj to specifically counter the defence’s arguments in those cases and incorporating the broadened provisions. The words ‘hatred’ and ‘contempt’ were added alongside ‘disaffection’. Section 153A was also added to the code to curb nationalist newspapers.

Tilak was brought back to court on sedition charges in the aftermath of anti-partition agitation, and brutal British repression in Bengal in 1908. The scope of the section was further broadened and the semblance of difference between ‘disaffection’ and ‘disapprobation’ was removed.

Under this framework, Satyaranjan Bakshi was arrested in 1927 for saying that the British government was following a policy of ‘divide and rule’, deposit of a press was confiscated because the paper published an article criticising local government for misusing and abusing its powers.

In 1910, Ganesh Damodar Savarkar was booked under sedition for publishing a series of allegorical poems. The court noted that Savarkar had used words with ‘double meanings’, and reference to Shivaji, and Hindu gods and goddesses was meant to preach war against the government.

The usage of sedition, therefore, was not limited to political domain, but included cultural domain as well. People were even prosecuted for kirtanas and reading Puranas under the sedition act.

Sedition in independent India

Given the challenges faced by newly independent India, the Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee of the Constituent Assembly chaired by Sardar Patel expressly included sedition as a ground for restricting free-speech.

However, when the draft came up for discussion, the provision was vehemently criticised and not included in Article 19(2) in the final copy of the constitution.

Under Article 13, the constituent assembly dictated that all colonial laws repugnant to the constitution would be void. However, the Section 124A wasn’t repealed by the Parliament and the battle reached the courts.

Ultimately, in 1962, in Kedarnath Singh case, the Supreme Court said that speeches or protests against parties or governments was no offence, but the attempts to break up India by force or persuasion would be under the Section 124A.

The apex court refused to strike down the provision in light of the separatist and anti-national forces, but made it cleat that he provision cannot be used against the strongly-worded criticism or opposition of the government.

The court limited the sedition charge to those attempting to incite people to use violence against the government established by law, and pernicious tendency to create public disorder or disturbance of law and order.