Torture Chambers, Comrade-Teacher Nexus: Shocking Details Of Communist Students Politics In Justice Shamsudeen Report

Mainstream media has long been accused of being unfair in its coverage of violence perpetrated by the Left-wing - even by leading left-leaning scholars.

J Shamsudeen committee report released in September 2019 which gave harrowing details of Left’s reign of terror in Kerala colleges, got close to zero coverage.

A 2007 article critiquing the coverage of Nandigram violence in Left-ruled Bengal gives insight into the reasons behind people losing trust in the media.

The incident of violence in Jawaharlal Nehru university on 5 January has had the whole nation polarised.

This wasn’t the first such incident in the JNU, a university notorious for violence and politics of intimidation. Both sides - ABVP, and the Left-led JNUSU claimed being victimised at the hands of the other side.

On top of it, many took to social media over Left leaders forcibly holding the university in a lock-down, and intimidating students, teachers as well as other university workers. The protesters reportedly also beat up the staff and the students who were a part of the registration process.

Later, in Naxal-style, posters with the photographs of some students and JNU alumni, who didn’t support the Left narrative, were pasted, labelling them as the collaborators of the attackers, along with a threatening message.

The names of three JNU professors were pasted publicly with the message that CHS (Centre for Historical Society) has declared them “out of bounds”.

A Dalit student of the same university, took to social media, and posted screenshots of him being removed from the university course group, and his photograph pasted, declaring him to be banished from his hostel, for not following Left’s commands.

“The JNU Left is a political upper caste which treats ABVP as politically untouchable. Within ABVP there is no socio- political untouchability. In the Left however, there exist undercurrents of caste hierarchy,” he wrote.

In the aftermath of the incident, the role of the media also came under the question-mark. The media was accused of presenting an incomplete picture. However, this wouldn’t be the first time that mainstream media channels who claim to be unbiased have been accused of underplaying or justifying Left-wing violence.

Justice Shamsudeen Committee Report

Kerala has been a hotbed of violence perpetrated by Left student groups in colleges. Different groups within the Left umbrella also fight among themselves.

After one such incident in a long series, when a University College girl tried to kill herself in May 2019. A ‘people’s independent judicial inquiry commission’, led by Justice (retd) PK Shamsudeen was constituted by social and educational activists to probe the matter.

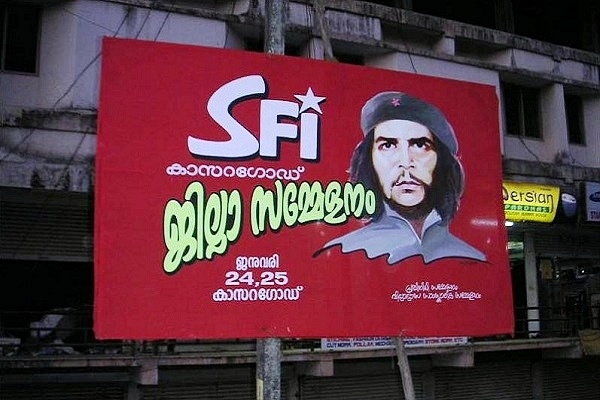

The report of the committee was released last September, and contained harrowing details of the ‘reign of terror’ unleashed by the SFI - the student-wing affiliated to the Communist Party of India, in the colleges across the state.

“The students narrated how the SFI activists physically assaulted and verbally abused them for not being a part of the outfit’s activities. They also complained about exam irregularities by SFI workers with the tacit support of college authorities,” Shamsudeen said.

Complaints also emerged against Left-affiliated teachers who turn a blind eye to the illegal activities of SFI leaders. Unlawful practices such as attendance waiver for SFI leaders and facilitating their re-admission were also raised during the hearing by students, teachers, rights activists and other stakeholders.

The report also pointed out that “torture chambers” existed in the colleges where SFI members would take the students who fail to toe the line.

Students are not allowed to file complaint in most of the colleges where SFI is in power. The commission reported that students are restricted from contesting students’ union elections on such campuses.

Despite the spate of violence - including a stabbing incident, and details of the accused in the case joining the state civil services by cheating in the exam - several mainstream media channels failed to give any coverage to the Justice Shamsudeen committee report. Example 1, example 2.

How media covered Nandigram

In 2007, Professor Vinay Lal of UCLA, wrote Reading Nandigram through ‘The Hindu’, criticising the coverage of the violence perpetrated by the Left government in West Bengal.

The article, though written for a specific publication, offers insights into different reasons behind people’s low-trust in the media in general - keeping ideology over the truth, use of ornamental English language to avoid questioning from the common people, borrowing ‘trends’ and arguments from the foreign ideological channels instead of original thinking, opportunism etc.

The article, published on Manas portal on 12 November 2007, is being reproduced in its original form here for the readers, only emphasis is added.

“Today’s The Hindu carries an editorial on the continuing carnage in Nandigram that would appear to confirm the impression that the newspaper occupies a distinct and indeed I should say distinctly odd place in English-language journalism in India. I have often wondered why the newspaper clearly seems unable to find Indian voices to fill its op-ed pages, which are dominated by reprints from the Guardian (and, occasionally, Le Monde).

Apparently we must hold to the view that the Guardian sets the gold standard for journalism, or at least somewhat meaningful commentary. Not for The Hindu the incisive pieces of Cairo’s Al-Ahram Weekly, since for the Indian intellectual, London, New York, or Paris are still the only places from where ideas emanate.

Or is it the case that The Hindu is run somewhat like a despotic state, where the writ of one man runs supreme, and that very few Indians meet the exacting ideological standards demanded of its contributors?

The Hindu must, after all, be among the few places where unabashed apologies for Stalin’s atrocities can still appear with the justification that all true revolutions are subject to some aberrations.

If The Hindu’s stifling left orthodoxies were not enough, it is now out to claim, judging from the editorial called ‘The Challenge of Nandigram’ (12 November), its place as the stern custodian of English constitutionalism and its alleged glories.

Not surprisingly, the paper has rushed to the defence of the Left Front, and the parties opposed to the government’s policy of transforming Nandigram into another hub for capitalist expansion are described as having brought ‘administration and development work to a halt’.

All the sustained critiques of ‘development’ cannot detract from what The Hindu perceives to be its magical qualities, and the newspaper dutifully trots out impressive sounding figures. Thus, readers are told, owing to the actions of the opponents of development, ‘15,000 children could not be given pulse polio doses; Rs. 2 crore worth of expenditure on health infrastructure has had to be abandoned . . . and Rs. 2 crore worth of investment on electrification could not be made.’

Though at least three people were killed in the firing initiated by CPM cadres or goons working at the party’s behest, a denunciation of West Bengal Governor Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s constitutional improprieties takes up the greater part of The Hindu’s lengthy editorial.

In a statement released last Friday by the Governor’s office, Gandhi had expressed anguish at the events in Nandigram and stated unequivocally that ‘the manner in which the recapture of Nandigram villages is being attempted is totally unlawful and unacceptable.’

Gandhi critiqued the CPM for turning Nandigram into a ‘war zone’ and called for the removal of barriers placed by the CPM that had prevented activists and journalists from going to Nandigram. Though the CPM did not press for Gandhi’s recall, it lashed out at him for having ‘out-stepped the Constitutional limit of the highest office of the State’.

Accusing him of violating the neutrality which the occupant of the Governor’s chair is bound to preserve, CPM’s West Bengal Committee feared that Gandhi’s rash pronouncements ‘will only embolden the forces determined to destabilise peace and democracy in the State in a most undemocratic manner.’

It is amusing, to say the least, to hear of CPM’s avowed dedication to ‘peace and democracy’ apropos the events in Nandigram. But it is The Hindu’s pompous invocation of the great lessons of English constitutionalism that beggars the imagination.

The newspaper reports that the Governor’s office, like that of the British monarch or the Indian President, is bound by restraints that must be observed if the ‘greater democratic legitimacy’ of representative government is not to be undermined.

According to this esteemed newspaper, the ‘classic 1867 exposition of the role of the British monarch by Walter Bagehot’ set the standards by which the Governor of an Indian state should abide. Thus, as The Hindu’s editorialist quotes Bagehot, ‘the Sovereign has . . . three rights – the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, the right to warn. And a king of great sense and sagacity would want no others. He would find that his having no others would enable him to use these with singular effect.’

Gopalkrishna Gandhi, the newspaper alleges, vastly overstepped these limits and stepped into the fray by issuing nakedly partisan statements that gave comfort to the government’s enemies.

Let us leave aside for the moment the question of the Hindu’s own blind advocacy of CPM’s politics. Gopalkrishna Gandhi’s partisanship is described as having consisted in challenging ‘the wisdom of the government’s approach’ and ‘[coming] down on the side of the critics of its action’; moreover, ‘Mr. Gandhi laid himself open to the charge of remaining silent when the supporters of the Left Front were at the receiving end.’

This is rather akin to the rants of middle-class Hindus who complain that Muslims condemn Hindu extremism but do not sufficiently condemn Islamic extremism. The Hindu’s editorialist sounds like a petulant child convinced that the sibling is allowed more liberties.

One might have thought that the newspaper would have reflected with some pride on the presence of a Governor who, cognisant of the great moral issues thrown up by developments at Nandigram, Singur, and elsewhere, has sought to indicate that violence cannot be allowed to overwhelm those most affected by these developments into subjugation and abject surrender. Gandhi has adopted a position that most others similarly placed would not have had the courage to embrace.

There is, in equal parts, something comical and pathetic about The Hindu’s trumpeting of Walter Bagehot. The last Englishmen, it has been said, are to be found in India; now, it appears, English constitutionalism will find its most ardent defenders in the pages of an Indian newspaper otherwise known for its fervent advocacy of Marxist pieties”.