A Date Bengal Should Not Have Forgotten

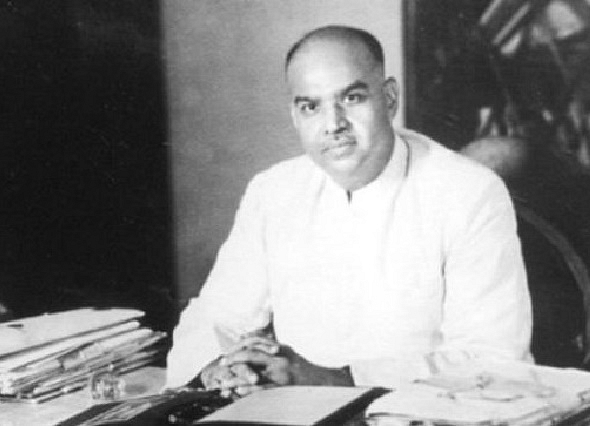

On 6 July, 115 years ago, one of Bengal’s greatest sons was born to an illustrious family. Had it not been for him, there would have been no West Bengal today.

It is a matter of great shame, therefore, that West Bengal’s Bengali Hindus have largely chosen to forget Mookerjee’s stellar role in ensuring a safe homeland for them.

Last Wednesday (6 July) passed by unnoticed, and uncelebrated, in an ungrateful West Bengal. On this day 115 years ago, one of Bengal’s greatest sons was born to an illustrious family. Hadn’t it been for him, there would have been no West Bengal today. Hadn’t it been for him, this then-eastern state of India would have been part of East Pakistan, and subsequently, Bangladesh, where Hindus are forcibly converted to Islam, hacked to death, driven out and relegated to living as worse than second-class citizens.

If Bengali Hindus have a homeland today in the form of West Bengal, it is all due to Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee, the founder of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh. Though Mookerjee was vehemently opposed to the partition of India as demanded by Muhammad Ali Jinnah and his All India Muslim League, when he realised that partition was inevitable, he prevented the whole of Bengal province (East and West Bengal) from going to Pakistan. It was due to his efforts that the ‘Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement’ could successfully lobby for the partition of Bengal and ensure a safe homeland for Bengali Hindus.

It is necessary here to go back to pre-Independence history. After the arrival of the British, Bengali Hindus took advantage of Western education and moved ahead of the Muslims in the province. But education and enlightenment, which the British encouraged, had a negative fallout: revolutionary fervour started rising in Bengal, and many young men, almost all of them Bengali Hindus, started revolting against British. The British felt they had to create a divide between Bengali Hindus and Muslims and, with active encouragement from some privileged Muslims, partitioned Bengal in 1905 to create a Muslim-majority East Bengal (including Assam) and a Hindu-majority West Bengal (comprising Bihar and Orissa as well).

But here, too, the British played a diabolical game. Bengali Hindu-majority districts of West Bengal like Manbhum, Singhbhum, Santhal Parganas and Purnea were awarded to Bihar sub-province and Hindu-majority Cachar in East Bengal was awarded to Assam sub-province. Thus, Bengali Hindus became a minority even in West Bengal. The partition triggered massive protests spearheaded by the Indian National Congress, which launched the Swadeshi movement. The British were forced to annul the partition in 1911. But more games were being played by the British to subdue the Bengali Hindus: the Indian Councils Act, 1909, was passed and formed the basis of the Government of India Act, 1919, through which proportional representation along communal lines was introduced, and Bengali Muslims were awarded more seats in the Bengal Legislative Council than Bengali Hindus. Of the 144 seats in the Council, 46 seats were kept reserved for Bengali Muslims while Bengali Hindus were awarded 39 seats. The rest were for institutions, Europeans, Anglo-Indians and others.

The Communal Award of 1932 then allotted 119 seats for Muslims in the 250-member Bengal Legislative Assembly, and only 80 seats were kept in the general category, of which 10 were reserved for ‘lower caste’ Hindus.

Thus, the British ensured that the united province of Bengal, or the Bengal Presidency, would be ruled by Muslims. That is what happened. In the first provincial elections held in India in the winter of 1936-1937, though the Congress emerged as the largest single party with 54 seats, it declined to form the government or ally with the Krishak Praja Party (which won 35 seats) founded by Abul Kasem Fazlul Huq, even though the two parties fought the polls as informal allies. Haq then secured the support of Jinnah’s Muslim League (which won 40 seats) to form a coalition government along with the support of 25 Europeans, 23 Independent Scheduled Castes and 14 Independent caste Hindus. Huq became the Prime Minister of Bengal.

But Huq’s tenure was marred by many controversies and rising communal tensions. The Krishak Praja Party also broke up, and the 23 Independent Scheduled Castes withdrew support to the Huq government. His relations with the Muslim League also soured after Jinnah asked him to resign from the Viceroy’s Executive Council to which he was appointed by the then Viceroy Victor Alexander John Hope.

Earlier, however, Huq had moved the Lahore Resolution at the Lahore session of the All India Muslim League in March 1940 calling for the establishment of ‘independent states’ for Muslims in the northwestern and eastern parts of British India. This became the basis for the creation of Pakistan.

When his ministry fell in 1941, he sought the support of the Akhil Bharatiya Hindu Mahasabha headed then by Syama Prasad Mookherjee and a breakaway faction of the Congress led by Sarat Chandra Bose, elder brother of Subhas Chandra Bose. Sarat Bose and many other Bengali Hindus had broken away from the Congress after Subhas Bose was forced to resign as President of the Indian National Congress by Gandhiji and his coterie in 1939.

The Progressive Coalition Ministry headed by Huq, with Mookerjee as finance minister, assumed office in December 1941 and functioned till March 1943. Huq was succeeded by Muslim League’s Khawaja Nazimuddin, a scion of the Dhaka royal family, who reigned till March 1945. It was during his tenure that the infamous Bengal famine of 1943, which took the lives of more than 3 million people, occurred. The provincial government acted in a highly partisan manner, providing relief to Muslims and ignoring Hindus. Mookerjee and other Hindu Mahasabha leaders protested vigorously against this. After World War II, elections were held in 1946, and the Muslim League won 113 seats in the 250-member Assembly and formed the government with HS Suhrawardy as the Prime Minister in April 1946.

Communal tensions in Bengal were at their peak by the time Suhrawardy took over. And he accentuated those tensions through his blatantly and shamelessly communal actions. Suhrawardy’s recruitment of 600 Punjabi Muslims into the Calcutta Police, the way his government allowed them to loot Hindu households and rape and molest Hindu women, and the anti-Hindu policies he pursued (all of which have been extensively documented and is beyond refutation) ultimately convinced many Bengali Hindus that a separate province for themselves was a necessity to escape harassment, torture and even annihilation at the hands of the majority Muslims of Bengal.

Amalendu Prasad Mukhopadhyay, a close disciple of Mookerjee and former head of department of political science at Raja Rammohan Roy Mahavidyalaya at Hooghly district of West Bengal, documents here how, during his visits to the eastern part of Bengal, Shariat rules were being enforced by the ruling Muslim League. He writes: “Customary ritual practices of Hindus (like) blowing of conch-shells, use of vermilion, worship of basil sapling (tulsi) in domestic courtyard was banned”. Tarun Vijay, Member of Parliament in Rajya Sabha and Director of the Delhi-based Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, quotes Mookerjee as writing in 1945:

“In provinces where constitutional powers have passed to the hands of Moslem ministers, reports of oppression and injustices (on Hindus) daily pour in. I myself can bear testimony to a systemic policy being pursued by the (Suhrawardy) Ministry now in power in Bengal which is aimed at crippling the Hindus in every sphere of life--economic, political and cultural”.

But Mookerjee, an ardent nationalist, remained opposed to the idea of partition of India as proposed in the 1940 Lahore declaration. In a speech on 12 November 1944 at Ludhiana, he declared:

“There can be no compromise with any fantastic claim for cutting India to pieces, either on communal or on provincial considerations. India has been and is one country and must remain so, whatever self-constituted exponents of so-called Hindu-Moslem unity may declare. It is a most dangerous pastime to try to placate that section of Moslems who think it beneath their dignity to love in India as such and therefore demand a territory of their own, sovereign and independent, carved out of our motherland, a territory where crores of Hindus will continue to live, bereft of their Indian nationality. It is nothing short of stabbing Indian liberty and nationalism in the back...I sincerely hope that in the period of struggle that lies ahead of us, Hindus, Moslems, Christians, Buddhists and all others will merge themselves wholeheartedly in the cause of Indian emancipation and thereby baffle the machinations of those reactionary elements that create disunity or dissension among ourselves or seek to thrive on them”.

But the Calcutta riots of August 1946 and the subsequent Noakhali riots in October-November 1946 in which thousands of Hindus were butchered, their homes looted and properties confiscated, Hindu women raped and molested and an unspecified number forcibly converted to Islam convinced Mookerjee and other Hindu Bengali leaders like Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy (who later became chief minister of West Bengal), Nirmal Chandra Chatterjee (father of former Lok Sabha speaker Somnath Chatterjee), economist Nalini Ranjan Sarkar (who became West Bengal finance minister) and many others that division of Bengal in order to provide a safe homeland for Bengali Hindus was inevitable.

Led by Mookerjee, the Bengal Provincial Hindu Mahasabha launched an intensive campaign for partition of Bengal in February 1947. In the first week of April 1947, a three-day Bengali Hindu conference at tarakeshwar that was attended by 400 delegates from all over Bengal and 50,000 others passed a formal resolution demanding a separate homeland for Bengali Hindus. Simultaneously, the Bengal unit of the Indian National Conference also passed a similar resolution.

Mookerjee also delinked the movement for partition of Bengal from the demand for partition of India. At a public rally in Delhi on 22 April 22 1947, he declared that even if the Muslim League accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan that recommended a united India, a separate province needed to be constituted in the Hindu-majority areas of Bengal.

Mookerjee roped in the media, including leading newspapers of those times like Dainik Basumati, The Statesman, Amrita Bazar Patrika, and others to campaign for partition of Bengal. He was instrumental in securing support from leading intellectuals like Meghnad Saha, Jadunath Sarkar Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Suniti Kumar Chatterji and others to lend their weight to the partition demand. Mookerjee convinced the Congress to hold a joint public rally with the Hindu Mahasabha to demand the partition of Bengal. The rally held on 7 May in Calcutta and presided over by Jadunath Sarkar, delivered a major boost to the partition movement.

Mookerjee successfully turned Jinnah’s argument for partition of India on its head for the partition of Bengal. If 35 percent of Muslims cannot live in India with 62 percent Hindus, there was no way that 42 percent Hindus can stay in a Bengal with 54 percent Muslims, asserted Mookherjee. It is said that when Jinnah lamented the loss of West Bengal to Mountbatten, the latter pointed out that Mookerjee had paid Jinnah back in his own coin. Jinnah’s arguments for partition of India to create a separate homeland for Muslims was used by Mookerjee to make a strong case for a separate homeland for Bengali Muslims.

Mookerjee also won over jurists of the Calcutta High Court to support the movement, and nearly all the Bengali Hindu lawyers signed a petition demanding the partition of Bengal. Hindu businesspeople and chambers of commerce, including the legendary Ghanshyam Das Birla, also rooted for the demand. Mookerjee’s efforts gave results, and on June 3, Lord Mountbatten declared that Bengal would be partitioned. On 20 June 1947, all legislators of the Bengal Legislative Assembly from Hindu-majority areas of the province voted for the partition of Bengal and creation of a separate homeland for Bengali Hindus. Thus, West Bengal was formed.

Mookerjee and leaders of the Hindu Mahasabha and Bengal Congress lobbied successfully for retaining Calcutta within India. They also successfully defeated a diabolical plan hatched by Suhrawardy for an independent and united Bengal. Suhrawardy and other Muslim leaders were alarmed that Hindu-majority Calcutta, with all its academic and financial institutions, as well as the Hindu-majority western part of Bengal province that had almost all industrial units and factories, the Calcutta port and other infrastructure, would go into the hands of Hindus, and Muslims would be left with the poorer and lesser developed eastern part of Bengal.

Hence, they mooted the idea of a united and independent Bengal and obtained support from a handful of Hindu leaders like Sarat Chandra Bose. The same Suhrawardy who facilitated the Calcutta and Noakhali riots, had the blood of tens of thousands of Hindus on his hands, and formulated anti-Hindu policies and allowed Muslims to kill, rape, loot and forcibly convert Hindus, suddenly turned a votary of Hindu-Muslim unity and advocated the idea of a united and sovereign Bengal. Mookerjee saw through this game and opposed it vehemently. Suhrawardy, he rightly argued, would ultimately merge such a united Bengal with Pakistan.

Had the partition of Bengal not happened and a united Bengal been part of Pakistan or a sovereign country, there is no doubt that Bengali Hindus would have been persecuted and made to live like second-class citizens. In 1947, Muslims formed 53.4 percent of Bengal’s population and Hindus 41.7 percent. A Muslim-majority Bengal would have been a living hell for Hindus.

It would be pertinent here to cite the example of Jogendra Nath Mandal, an ardent advocate of Dalit-Muslim unity who opposed the partition of Bengal, supported the Muslim League and became Pakistan’s first law and labour minister. Mandal had said and written that he chose “secular Pakistan” over “communal India”. It took but just a year for his illusions to shatter. Systematic targeting of Hindus, including lower caste Hindus, in Pakistan and then the killings of Hindus in East Pakistan in 1950 led Mandal to flee that country and seek refuge in West Bengal. His anguished resignation letter to Pakistani Premier Liaquat Ali Khan provides a sickening account of the plight of the Hindus in East and West Pakistan.

And that would have been the fate of all Bengali Hindus had Mookerjee not led the movement for partition of Bengal. The number of Bengali Hindus in East Pakistan, and now Bangladesh, has fallen drastically from 22.5 percent in 1947 to a little over 5% today. Hindus are a persecuted lot in Bangladesh and live like second-class citizens there. Bengali Hindus safely ensconced in West Bengal should be eternally thankful to Syama Prasad Mukherjee that they don’t share the same fate as their counterparts across the international border.

It is a matter of great shame that West Bengal’s Bengali Hindus have largely chosen to forget Mookerjee’s stellar role in ensuring a safe homeland for them.