After Shiv Sena, TDP And Manjhi, Who’s Next On NDA’s Exit List? Well, The Rush May Be Over

The question: Who’s next to walk out of the NDA?

The answer: Almost no one of consequence.

With two National Democratic Alliance (NDA) partners, Shiv Sena and Telegu Desam, already headed for the exits, the question to ask is who’s next. The answer, surprisingly, is this: almost no one of consequence. The ones who found themselves losing out, including Jitan Ram Manjhi in Bihar, have already done so. The others who are unhappy with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) will not benefit from an exit, especially when it is far from clear that the Narendra Modi charisma is diminishing.

Consider the options before some of the major allies: the Akali Dal, which brought defeat upon itself, will need the BJP if it is to hold on to its seats in Punjab in 2019. Smaller allies like Ram Vilas Paswan’s Lok Janshakti Party (LJP), and Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal United JD(U), have no particular future outside the NDA, especially since the latter has burnt his bridges with Lalu Prasad Yadav’s Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), and Paswan rival Manjhi has already moved to the Lalu camp. Finding space for another Dalit party in the anti-Modi alliance will be tough.

As for smaller parties like Apna Dal in Uttar Pradesh, or the Rashtriya Lok Samata Party in Bihar, they could theoretically choose to exit the NDA, but this will be more about bargaining to retain their existing seats in the Lok Sabha (two in the case of the former and three in the case of the latter). But their bargaining power is low, as the BJP can well supplant them by offering seats to members of the communities they represent. In national elections, small regional parties cannot set the agenda, unless they have a big vote base in a state.

Now, let’s look at why the two parties exiting the NDA are doing so.

The Telegu Desam Party’s (TDP) decision to pull out its two ministers from the Union cabinet is said to be in protest against the Modi government’s refusal to accord special category status to Andhra Pradesh. But the real reason is political necessity.

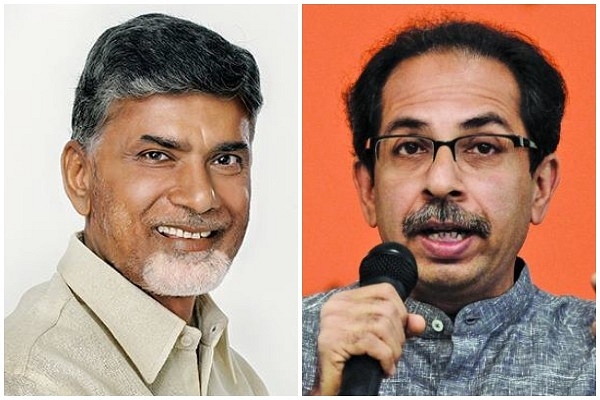

Chief Minister N Chandrababu Naidu faces a tough election in 2019, where his main opponent will be YSR Congress’ Jagan Mohan Reddy, who may benefit from any anti-incumbency mood. With Reddy’s party threatening to get all its MPs to resign shortly on the special category status issue, Naidu had no other option but to pre-empt him. If he was seen to be ineffective in wangling more out of the BJP despite being in the central ministry, Naidu would have lost face with his voters.

Naidu’s move towards the exit can only be understood in the context of the competition he faces in Andhra Pradesh from YSR Congress. In the 2014 elections, Naidu won by receiving 32.5 per cent of the vote, just 4.6 per cent ahead of YSR Congress. (Vote share figures are for whole of undivided Andhra Pradesh, not the bifurcated state). In the assembly, he got 103 seats to YSR’s 66. In the Lok Sabha, Naidu has 15 MPs to YSR’s eight. The point to underline is this: if, at the height of the Modi wave, Reddy could do as well, Naidu clearly has reasons to worry when the tide may be against him in 2019. The last thing he needs is a double anti-incumbency, one against him, and another against his ally BJP.

It needs no genius to figure out that YSR Congress could possibly dethrone Naidu, especially if Reddy kisses and makes up with the Congress.

Naidu’s future thus depends on distancing himself from the BJP so that he does not lose the minority vote. He has to generate issues out of thin air (special status, etc) so that he can pose as an inveterate fighter for the state’s interests.

The problem with the demand for special category status is that it is impossible for any central government to concede. Andhra Pradesh cannot, by any stretch of imagination, be deemed to be a special category state when Bihar, a far poorer state, does not get it. The 11 states currently in the special category are either hill states with a difficult terrain, or located in the north-east: Himachal, Uttarakhand, Jammu and Kashmir, Assam, Arunachal, Tripura, Sikkim, Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland and Mizoram. By which logic can Andhra be fitted into this category? At best, the Centre can offer special packages to build infrastructure in the capital city and elsewhere, so that the Andhra economy benefits from it. Naidu knows this is the best the Centre can do for him, but politically it is best to demand the impossible and claim victimhood status.

Naidu badly needs to win in 2019 to fulfil all his promises to his own support groups, especially those who allowed their lands to be pooled to create Andhra’s new capital, Amaravati. Among those most willing to pool land were Naidu’s Khammas, with Kapus and Reddys unwilling to trust Naidu’s promise of delivering high returns on the developed land that they will get in return.

In fact, if YSR Congress wins in 2019, the whole land pooling idea may get reimagined, leaving those who pooled land in limbo and uncertainty.

As for the Shiv Sena, the other ally that is miffed with the BJP, its predicament in Maharashtra is simple: its Hindutva political constituency overlaps with that of the BJP, and since the BJP is the stronger party, over time it can take over the Sena’s vote bank. Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis is doing just that by appropriating Shivaji for the BJP. The Sena needs to fight the BJP purely for survival as a separate entity.

For the BJP, it makes sense to make concessions to the Shiv Sena to keep the alliance intact in Maharashtra (where it may face a united opposition), but in Andhra Pradesh it will be better off letting Naidu fight the elections alone. It can benefit from whoever wins, especially if it needs allies after 2019. It can then choose between TDP, YSR Congress and Telangana Rashtra Samiti, which is sure to retain Telangana.

BJP still holds some high cards despite the exit of some allies.