Article 370 Legal Challenge: Not Just Modi Government, But Supreme Court Itself Will Be On Test

The SC has a wonderful opportunity to deliver a path-breaking judgement that will end separatism and discrimination based on gender and region in the Article 370 case.

It can end an article that undercuts the Indian Constitution and fans the fires of separatism, or gives it a new lease of life.

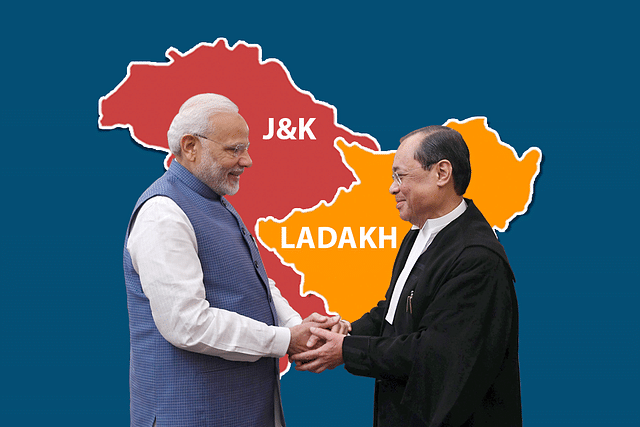

When the Supreme Court begins to hear the various petitions on Article 370 from Kashmiri and some others, it should remember one thing: it is not the Narendra Modi government’s decisions alone that are on test, but its own commitment to national unity and constitutionalism.

The grey area is the method used by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government under Modi to achieve the effective abolition of Article 370; it used provisions of the same article to junk the Jammu and Kashmir Constitution of 1956 and replace it with the Indian Constitution.

The Presidential Order and the legislations passed in Parliament earlier this week also replaced the words “constituent assembly” with “state assembly” as the organ that needs consulting on Article 370. The Centre can thus claim that since the state assembly does not exist currently, Parliament is empowered to decide on its behalf in the meanwhile.

The Supreme Court will essentially have to decide whether Parliament can substitute this vital process of consultation with elected state representatives with the opinion of the Governor of the state — and opinion in the legal fraternity is divided on this.

In the end, if the Supreme Court is going to rule against the changes made, it will be deciding the case on a technicality, and not larger principles. The questions it needs to ask itself are simple.

One, as the supreme arbiter of the Indian Constitution, is it not the Supreme Court’s job to ensure the Constitution is supreme, and valid across the length and breadth of the country? Can any legalistic interpretation in favour or restoring Article 370 absolve it of the responsibility of again shrinking the ambit of the Indian Constitution?

Two, when needed, the Supreme Court has read all kinds of meanings into the provisions of the Constitution. For example, it reinterpreted Article 124, which empowers the government to appoint judges to the higher judiciary in consultation with the Chief Justice, to mean that the collegium alone will decide how judges are appointed. The Supreme Court has also used Article 142 to make laws instead of merely interpreting them.

Three, it has often used the concept of “basic feature of the Constitution” to deliver judgements without clearly delineating what listing all basic features are. In a judgement last year, a constitutional bench read the right to privacy as part of the fundamental right to life and liberty even though the Constitution makes no mention of it. But the right to property, once a fundamental right clearly mentioned in the Constitution, and presumably a basic feature, saw the Supreme Court looking the other way when it was erased from the statute book in the late 1970s.

Four, full-scale constitutional amendments to set up the National Judicial Appointments Commission, which were backed by near total unanimity in Parliament and legislatures, were junked by a constitution bench — a bench which could easily be said to have sat in judgement in a case in which it was itself an interested party.

Five, equality of treatment should surely be a basic feature, but the Supreme Court did nothing about Article 35A, which came in via a presidential order and without Parliament legislating it, in order to deny Kashmiri women land ownership rights if they married non-residents. Restoration of Article 370 will mean reversing this reform too.

Six, in the age of globalisation and cross-border movements of people, technology and ownership, is the Supreme Court going to make J&K alone an island that can keep businessmen and migrants out on a whim and fancy? Why then blame a Raj Thackeray for beating up Bihari migrants?

The Supreme Court has a wonderful opportunity to deliver a path-breaking judgement that will end separatism and discrimination based on gender and region in the Article 370 case. It can end an article that undercuts the Indian Constitution and fans the fires of separatism, or gives it a new lease of life.