By Saying No To CJI Impeachment, Naidu Has Stymied Congress-Fuelled Plan For Judicial Chaos

The only logical way forward is for both the Congress and the BJP – and some of the other major parties – to agree on creating a judicial accountability bill whereby there is an institutionalised process for dealing with judicial misdemeanours, with the impeachment process itself being a move of the last resort.

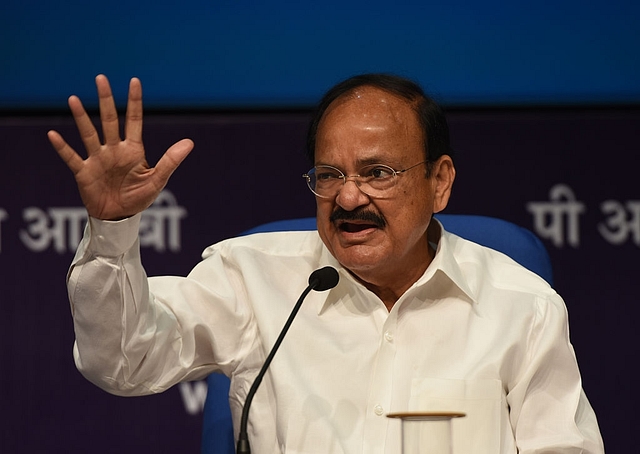

It is good that the Rajya Sabha Chairman, Venkaiah Naidu, has nipped the Congress conspiracy to immobilise the Chief Justice of India, Dipak Misra, by rejecting the impeachment move as unwarranted. The charges, said Naidu, are based on mere suspicion, and not proof. (Read the full text here)

Under article 124(4) of the Constitution, “A judge of the Supreme Court shall not be removed from his office except by an order of the President passed after an address by each House of Parliament supported by a majority of the total membership of that House and by a majority of not less than two-thirds of the members of that House present and voting has been presented to the President in the same session for such removal on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity.”

Naidu’s order points out – fairly – that no case of misbehaviour or incapacity has been demonstrated by the current CJI Dipak Misra.

The Congress-led motion mentioned five reasons for seeking his impeachment: these included allegations that he refused permission to prosecute an Allahabad High Court judge allegedly involved in a bribery scandal; that he returned a land allotment based on a false affidavit only when he was being elevated to the Supreme Court; and that he abused his control of the roster by arbitrarily allotting cases to various benches.

Naidu says he has studied all the five charges, and the documents produced to support the claim for impeachment, and had come to the conclusion that no case under article 124(4) had been made out. He emphasised that the facts were not sufficient for “any reasonable mind to conclude that the Chief Justice of India…can be ever held guilty of ‘misbehaviour’.”

Naidu pointed out that the phrases used in the opposition notice on impeachment were uncertain and inconclusive to suggest misconduct. To say that the CJI “may have been” involved in a conspiracy of paying illegal gratification”, or that “he too (the CJI) was likely to fall within the scope of investigation”, or that he (the CJI) “appears to have ante-dated an administrative order” means the opposition was acting on the basis of mere suspicion rather than hard facts.

Naidu also emphasised that some matters had to be resolved within the Supreme Court in order for the institution to retain its independence. Given these objections, he was of the “firm opinion that the notice of motion does not deserve to be admitted.”

The decision will, of course, be criticised by the opposition, which will see this as a political bailout for the beleaguered CJI, but when the impeachment move itself was political, it is logical that its rejection was also political. The fact that the Congress party was already calling for the CJI to recuse himself from hearing cases while the impeachment motion was pending shows that the underlying motive was to prevent him from hearing any cases.

In a sense, by giving his decision quickly, Naidu has prevented the Supreme Court from going into limbo and an extended phase of leadership uncertainty.

Consider the real danger the country would have been in if the CJI was immobilised, and the next four judges of the collegium, Justice Chelameswar, Justice Ranjan Gogoi (the next CJI), Justice Kurian Joseph, and Justice Madan Lokur – who raised a banner or revolt against the CJI in January – were also subject to a similar political assault by the ruling party. If the Congress can seek to render the CJI impotent, it would have been equally possible for another group of MPs to seek to impeach the four rebel judges. These judges broke rules of propriety by coming out and addressing a press conference in January, alleging that certain things were not in order, including the allocation of cases by the CJI. In fact, former judge RS Sodhi had, at that time, called for the impeachment of the four judges, but wisely the government decided that the rift in the upper judiciary must be addressed from within.

It is also worth recalling that several senior legal luminaries have been unhappy with the move to impeach the CJI. Among the critics of this Congress attempt to politicise the fight against the CJI were former Law Minister Salman Khurshid, former Attorney General Soli Sorabjee, senior counsel Fali Nariman, and former Lok Sabha Secretary General Subhash Kashyap.

Justice Chelameswar himself has pointed out the impeachment cannot be a solution to all problems in the judiciary.

The only logical way forward is for both the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party – and some of the other major parties – to agree on creating a judicial accountability bill whereby there is an institutionalised process for dealing with judicial misdemeanours, with the impeachment process itself being a move of the last resort.

The Congress is guilty of making impeachment a political tool to get its way, and for this it is doubly guilty. It should thank Venkaiah Naidu for saving it from this suicidal decision to go after the CJI on the basis of mere suspicion.