Coronavirus: What Is Kerala Government Up To — Flattening The Curve Or The Numbers?

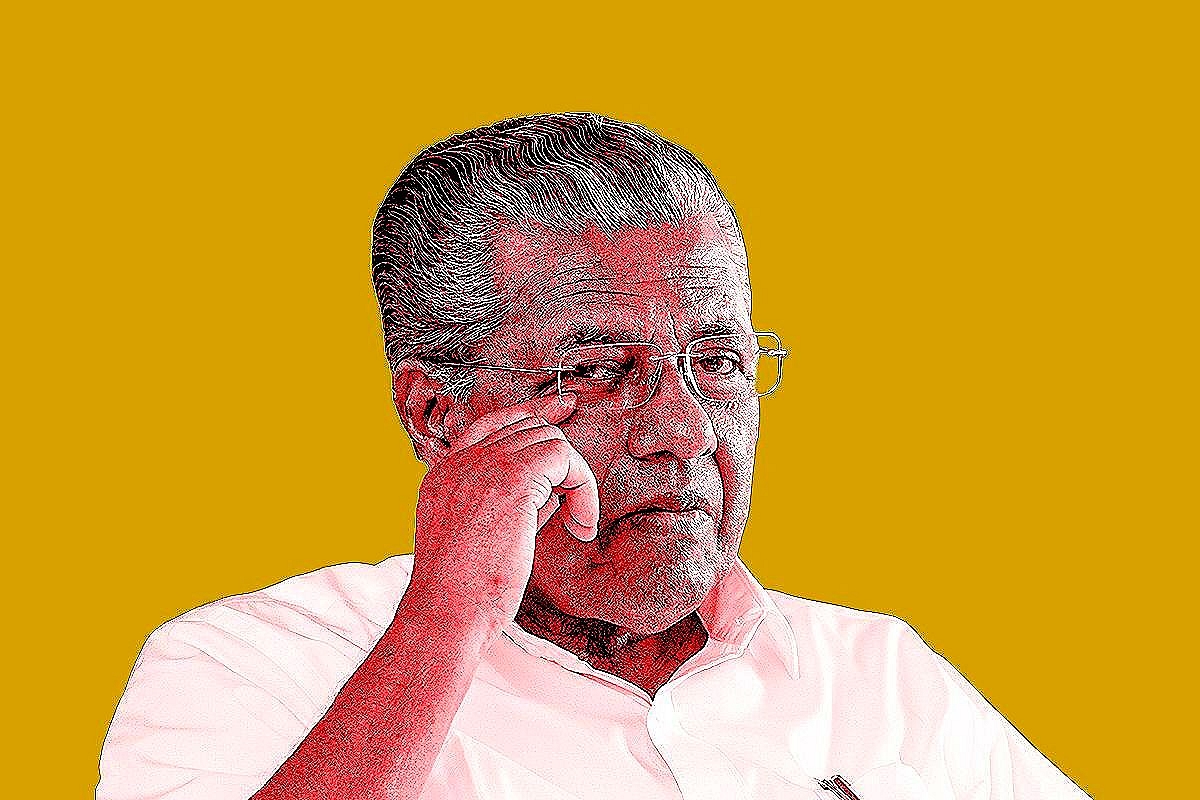

Kerala has not flattened the coronavirus curve, and yet the Pinarayi Vijayan government seems to be keen on starting a staggered return to normalcy.

Here are some hard questions that he will have to answer including how credible the state’s epidemic data is.

Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan’s recent move to curb lockdown restrictions in parts of the state raised quite a few eyebrows. Vijayan appeared to be unilaterally sending out a message, that the Wuhan coronavirus epidemic was abating, by which, Kerala could now commence a staggered return to normalcy.

The rash move was toned down only after his office received a sharp rap on the knuckles, when the Union Home Ministry warned such states against violating instructions.

Vijayan’s haste has thus forced a review of the situation in Kerala, and hard questions must now be asked of him:

- How valid are the Vijayan government’s epidemic statistics?

- Do they stand up to scrutiny?

- Why are they not being questioned?

The answers, far from being reassuring, raise concerns in the manner in which Vijayan and his Marxist government have both tackled the epidemic, and reported it.

- First, Kerala has not ‘flattened the curve’, whatever the Marxists’ global PR brigade may say. On the contrary, an abrupt, intriguing trend shift is seen to have taken place, coinciding with revelations of the Nizamuddin Markaz cluster in Delhi.

- Second, the state’s mortality rates, while thankfully low, test both credulity and global averages.

- Third, there has been an inexplicable drying-up of patient information.

- Fourth, serious omissions persist with regard to the intensity and extent of the Tablighi Jamaat cluster’s impact upon Kerala.

- Fifth, the Congress-led opposition (The United Democratic Front, or UDF) has curiously refrained from asking probing questions regarding management of the epidemic, and concentrated instead on trying to link Vijayan to an alleged corruption scandal.

Let us look at each of these issues in sequence:

1. Wuhan Virus Cases In Kerala

As the chart below shows, Kerala and Maharashtra were consistently reporting the most number of daily cases in India. Then, for reasons unknown, the rate of case reportings in Kerala began to dip around end March.

This coincided with revelations of the Tablighi Jamaat super-cluster in Nizamuddin, Delhi.

From that point on, the growth rate reduced considerably, with cases sometimes not being reported for over 24 hours. Readers can check this on the lower, brown line.

This shift from the pre-Tablighi trend was quite distinct, and can be clearly seen on the blue, cumulative cases curve.

A green, dashed line, representing projections of the pre-Tablighi trend up to end March, is added to highlight the divergence. It means that if the rate of cases being reported by Vijayan had continued as before, Kerala would have reached a thousand by 20 April, instead of the 407 cases it has.

Oddly, a number of commentators have eagerly interpreted this marked trend shift as a flattening of the curve. This is incorrect.

Kerala has not flattened the curve – only its growth exponent has gone down. Readers must appreciate this distinction fully: There is a difference between hitting a peak and reducing growth rates. The term ‘flatten the curve’ means reaching a brief plateau, after which the number of cases reported daily start declining.

On the contrary, in Kerala, what we have seen is no plateau, but a reduced growth rate, resulting in a slow but steady rise in cases for over three weeks.

One is not the other, and calling a low growth exponent a plateau is a fallacy; especially since there is no such thing as a month-long plateau. Instead, it points to something else – a something, which Vijayan needs to describe and explain.

2. Mortality

As on 20 April, the state government’s official mortality rate is 0.5 per cent (2/407). This is the lowest in the world. Unbelievable as it may seem, and discounting miniscule, isolated populaces like Qatar, Djibouti, Bahrain and Lichtenstein, no comparable region has yet reported such low mortality rates.

For proof, look at this cross-plot of percentage deaths versus percentage cases (of national totals), for the most-affected states of our country:

Kerala clearly stands apart, as an outlier. The closest (by a fair bit) is Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). This is understandable; representative data would be scanty in J&K, because of no-go areas due to the Pakistan-backed proxy war there.

But in Kerala, while such a low mortality rate is surely a blessing, it would attract attention because no war-like conditions persist there.

Look at it another way:

Once more, Kerala is a distinct outlier. How is this possible?

Are we to infer that mortality rates are unbelievably low because the medical facilities provided were better than world-class? If that is so, then the Kerala data deserves to be scrutinised in the minutest of details, so that vital insights may be gleaned; inferences, which would literally be of life and death value to the rest of the world.

Of course, if that were true, it would also create a contradiction: why then was there so much brouhaha over opening the border with Karnataka, so that patients in north Kerala might travel to Mangalore, to avail of medical treatment there? Remember that people even approached the Supreme Court for this?

Again, only Vijayan can clarify this point.

3. Drying Up Of Information

Until late March, Vijayan took great pride in making epidemic data details public. He made it a point to highlight the diligent work done by his staff. There was a surfeit of copious patient travel histories, colourful contact tracing charts, and information, on how and where the patients and their contacts were being quarantined.

There was both commendable glasnost and perestroika until a super-spreader returnee from the Middle East brazenly broke protocols to socialise widely – including attending functions of the Indian Union Muslim League. That’s when the first info-stutter took place.

This was followed soon thereafter by the now-infamous Tablighi benevolence. That was when the stutter braked to a stop. So must we ask Vijayan:

Why did the details dry up? What happened to the colorful contact tracing charts? What about the travel details? Why has none of this information been made public since the Nizamuddin cluster came to light?

One might not have asked, but for the fact that up to the end of March, Kerala was actually offering more information than analysts could handle. So, who turned off the tap? Why? Only Vijayan and his government can answer – and they must.

4. The Tablighi Jamaat Cluster

The chart below shows that the Kerala numbers have behaved wholly contrary to the other states affected by the Jamaat:

It’s a simple question: How did the rate of cases in Kerala decline after 29/30 March, even though it was reported that a large number of Malayalees had returned to the state after attending the Nizamuddin Markaz?

How come fresh clusters sprang up, and proliferated swiftly in all other states hit by the Jamaat tornado, but the exact opposite happened in Kerala?

Are we to believe that this is a rare coincidence? Hard as that may seem, and laudable while Vijayan’s efforts at containing the epidemic might be, such a coincidence appears, at least prima facie, as a statistical improbability.

The problem is, this serious discrepancy might actually have passed our scrutiny, but for Vijayan’s statement of 2 April. He said that all the attendees had been identified (read here, here and here). How could he say that so early on, when even today, the list of attendees is incomplete, and hundreds are reported to have switched off their phones and gone missing?

Why did he issue such an authoritative statement so quickly? What was the basis of his confidence? He can’t say ‘intelligence sources’ because his sources don’t operate outside the state, and also because, as on date, central agencies are still trying to finalise that list. We will know the truth only when Vijayan discloses all pertinent information.

Until then, the queries will only mount:

- What is the full and final tally of Markaz attendees from Kerala?

- How were they identified?

- Where were they quarantined?

- How many people did they come in contact with?

- When, where and how were those contacts identified and quarantined?

- What about the contacts of contacts? How many of them were tested?

- How many of those tested were virus-positive?

- Where are the contact-tracing details?

- How do the contact tracing and sample testing data match up?

- Why have they not been released to the public?

It would be uncharitable to dwell further on this point, save to say that if information is being withheld, it would not be a service to society. Surely, Vijayan understands the meaning of that, and will do the needful, swiftly.

5. The Congress-Led Opposition’s Intriguing Silence

Why has the opposition not asked the right questions yet? What happened to their usual caterwauling about all things irrelevant and inconsequential? Very strange indeed.

Is the Congress-led UDF opposition in Kerala silent because they anticipate deeply inconvenient answers? Does it have anything to do with the demographics of their coalition partners? Do they know something we don’t, a priori? Or are they just woefully ignorant of facts? We won’t know until they answer.

The Congress-led UDF certainly can’t say that their reticence stems from decency amidst a crisis, because then they will be asked where that same decency was, when they shamelessly asked for proof in the wake of Uri and Balakot.

And they certainly also can’t invoke as defence, a fig leaf of an attempt, to try and hang a corruption scandal on Vijayan (involving a Malayalee-run, US-based IT/PR firm; read here). That is because only an outfit of suspect competence would try to pull such a stunt, in the midst of a pandemic.

With their wealth of experience, the UDF should have known that corruption cases rarely sprout wings in the midst of a calamity. This one didn’t even get out of the egg!

Consequently, until the UDF constituent heads break their silence, and start to question the Marxists properly, they will have to live with the ignominy that their role was taken over temporarily by Swarajya.

So it must be asked: What is going on in Kerala under Vijayan?

Unfortunately, there are few answers. On the contrary, Vijayan has stopped releasing requisite patient details ever since the Tablighi Jamaat cluster came to light. He has not been adequately forthcoming either, on patient information, or on clusters. And he is yet to be asked probing questions on glaring, self-evident inconsistencies in case reporting, mortality, and epidemic spread.

Instead, his haste has been to try and lift lockdown restrictions in spite of persistent discrepancies. Therefore, his data management and reporting do not pass muster, especially following the Tablighi Jamaat virus dispersal event.

Be that as it may, it is Vijayan who heads the state of Kerala for now, so it is he who will have to answer the questions raised. If he doesn’t, and if the omissions noted are not satisfactorily resolved by Vijayan, his political future could adopt a new trend.

The people of Kerala would see to that. They have cures for everything.