In The Name Of Honour: Killing Of A Jat By Dalits Worsens Caste Complexities In Haryana’s Jind

In Jind, a group of Dalits killed a Jat allegedly because his family brought shame to them by marrying one of their women.

Jats are called “upper caste” and Dalits “lower caste”. Then, one wonders, why would the latter feel slighted when their women get a chance at upper social mobility?

Because caste-realities are more complex than we think.

Dr B R Ambedkar famously called the Indian village “a den of ignorance”. However, the epitaph used by the good doctor can very well be slapped on the nation’s urban chattering classes, public intellectuals, media persons and other assorted elites, when it comes to their understanding of social reality in the countryside.

Blame it on ignorance or poor education, but one encounters sweeping generalisations in their understanding of caste complexities in rural India. Such a stereotypical and generally poor understanding fail to explain atrocities and crimes where the conventional victim-and-perpetrator equation changes.

Such is a recent case in Haryana where a group of Dalits killed a Jat man allegedly because his family brought shame to them by marrying one of their women.

We are told that Jats are "upper caste" and Dalits are "lower caste". Given the traditional reading of caste relations, one wonders why would the latter feel slighted when their women get a chance at upper social mobility.

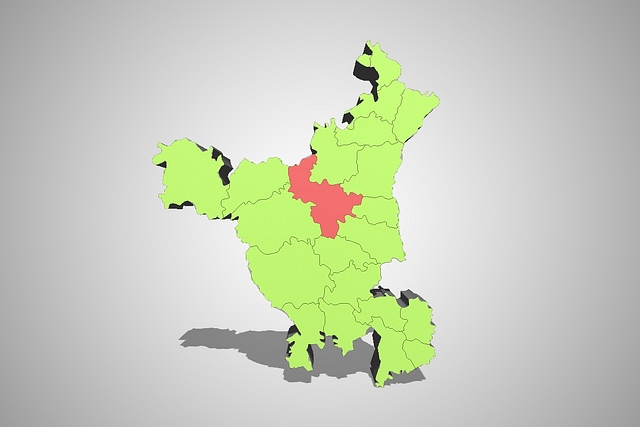

To unravel these complexities, Swarajya travelled to Haryana's Jind district to reach Chandralok Colony, the site of the incident.

The quiet here is unsettling, so is the sight of locks hanging outside the door of every other house. It is after several minutes of wandering that we see a resident. Turns out the families have gone to the police station for a round of questioning.

The resident points to a house at the end of the street, and another in the centre. The one in the corner is a one-storey structure with brick floor that looks desperately in need of attention. It belongs to the “upper caste” family who lost a 23-year-old son. The one in the centre, only a shade better, belongs to the “lower caste” family whose seven members are accused of murdering their young neighbour.

"The man (victim) was a gem. He should not have died," the resident tells us.

The deceased, Sompal, paid the price for his elder brother's "crime". The elder brother, Satyawan, married his neighbour - a woman from the Dhanak community - four years ago. The woman was already married with two daughters, but left her husband and family behind to live with Satyawan. They registered their union in a court.

The colony residents disapproved of the relation on moral grounds. "She (the woman) did grave injustice to her family. She wronged her husband. When he was shifting out of this colony with his daughters after the shameful episode, he stood in front of us with folded hands, and asked for forgiveness, if he had done anything wrong," a resident, who is also from the Dhanak community, tells us. Other accounts say the couple did not get along well, but that's another story.

Curiously, the residents are mum on the events of the fateful night when the murder happened. "It was midnight. We were fast asleep. We do not know. We didn’t even hear anything,” the resident, now joined by two more women, says.

But just we are chatting, a tractor full of women arrives. The man driving the vehicle is Ramjeet, the eldest of the three Jat brothers. He has also married outside the community - a ‘Nayak' from Punjab, a "lower caste". But his marriage happened with the consent of both the families.

Ramjeet hands over the keys of the tractor to its owner - a man leisurely playing cards - from whom he had borrowed it for a day.

Ramjeet narrates the incident: “I was sitting near the railway crossing, talking to my wife, who is currently in Punjab. It was around around 11 pm when Satish (the key accused) came in an inebriated state. He threatened me, saying that my younger brother had made a mistake by marrying a Dhanak girl for which he will have to pay. We had a heated argument over this. I got hit by a brick. In the ensuing scuffle, he was also hit."

“Within minutes of reaching home, Satish came to our house, this time with his wife, brother, brother’s wife, two cousins and wife of one of them. They started screaming, and demanded we come out of the house. My youngest brother opened the door when he heard the commotion. The mob hit him with a gandasi (sharp agriculture tool used for harvesting crop) and huge wooden sticks. When Satyawan, his wife and I came out, they attacked us too. We also sustained injuries. But as people in the colony started to come out, Satish and everyone else left."

The panic-stricken family took a badly injured Sompal to a hospital. "We arranged an auto to take our brother to hospital. But when we were passing in front of their (accused's) house, they started even beating the auto with sticks,” Ramjeet recounted.

The police, however, refutes Ramjeet’s claim about the weapon used. An official in Jind police station told Swarajya, "The medical reports of Sompal do not indicate use of any gandasi. It seems he died from the blows of a wooden stick below his ear. Sompal was handicapped. The family was also quite poor and he probably didn’t even have the strength to survive such heavy blows."

The burning question in the tale, however, is - how is that something that happened four years ago became a matter of honour all of a sudden, that too violent enough to claim a life? And how come a "lower caste" family feels "insulted" with association with an "upper caste" family?

Well, while the media seldom looks beyond fixed narratives, the reality is more nuanced.

Neighbours say the trigger could have been the better financial status of the Dhanak family, or even the fact that a person moving out of his caste, doesn’t matter if it’s upper or lower, attracts the ire of his community.

"Ye sab paise ka nasha hai (the accused are drunk on money). The accused have become well-off in recent times. The victim’s family lives in penury. This seems more like a case of bravado than honour killing,” says a man who is playing cards in a group outside a grocery shop at the beginning of Chandralok Colony. To supplement his argument, he says that the colony had never witnessed any incident of caste bitterness in the past. "Dhanaks, Nayaks, Jats, Brahmins, everyone lives here peacefully," he says. There are more Dhanak families than other groups, he adds.

A woman making haari (a mud stove) in the area, also a Dhanak, says inter-caste marriages are simply unacceptable.

There are others who share her view. "Ye sab dhaayi laakh ka khel hai (it's all a matter of Rs 2.5 lakh),” says a man from Nayak community. "Inter-caste marriages are on the rise because the government is encouraging this by giving Rs 2.5 lakh to such couples. This is highly condemnable. Everyone should just marry into one's own caste. It's good for everyone," he says.

But why would a “lower-caste” person support entrenchment of caste-system instead of calling for its annihilation? Shouldn’t he cheer the upward social mobility achieved by the Dhanak woman by marrying a Jat? The man says the community doesn't benefit by members moving out of the caste. "After marriage, she became a Jat. Her children will be Jats. So it doesn't change anything for us," the man replies.

Surprisingly, there are takers for inter-caste marriages. "This is the new normal. Because of a lack of brides, people go and purchase them from Bihar, Nepal, Kerala, etc. So what’s wrong in marrying into other castes? Isn’t it better than purchasing?” asks an old-timer as he smokes his hookah.

Meanwhile, the police has arrested the accused men in the case, but not the three women yet. The investigation is on, an official, who shared with us the copy of the first information report (FIR) in the case, said.

What if the caste equation was different in this case?

Member of the only other Jat family in Sompal's lane, told Swarajya bitterly that if it were a Jat man killing a Dhanak, there would have been a massive backlash. "If a Jat had killed a Dalit in a case of honour killing, the news would be all over the place and netas (leaders) would be making a beeline. Now, no one cares," he said, a view that others in the area agree with.

But again, the reality is more nuanced. Jind itself looks like a bundle of contradictions as just outside its mini-secretariat, two groups of Dalits protesting against caste atrocities are sharing space with a Jat group demanding reservation. Sitting and raising slogans in makeshift tents, both claim marginalisation and oppression.

“We have been sitting here since February. The political parties, be it in the government or the opposition, cannot care less for our demands,” says a Dalit protestor.

As such, Haryana fares better compared to most other big states as far as atrocities against Dalits are concerned. Jind, though, is different and is often in news for caste-related violence. Perhaps, for this reason, Dalit activism is quite noticeable in the city and the surrounding areas.

Rajat Kalsan, a lawyer and Dalit activist, tells Swarajya that the government has formally accepted all the demands made by them, but delivered on none of them. "The politicians make all kinds of promises when atrocity happens. But forget all about it later," he says.

Among others, their demands include a government job for the son of a policeman who was killed in the line of duty 33 years ago; monetary help by the government to Ram Kishan Grewal, ex-serviceman who committed suicide in Delhi during ‘one rank, one pension’ protest; and a government job for a family member of Satish Kumar, an Army officer martyred in Jammu three years ago.

The protestors also want a memorial or a bust erected in their honour because "officers from upper castes have it".

The Dalits are also agitating against alleged police inaction in cases of rape of Dalit girls by upper caste men. “A Dalit girl was raped by upper caste youths, who threatened her family to not file the case. The government had approved demand to give the victim's family two arms licences, one job and compensation. But they haven’t got the job, though the other two promises have been fulfilled," the activist said. He also alleged that in a case where a Dalit girl and a Dalit boy were found dead, the police are taking no interest in solving it.

“We have been sitting here for 150 days now. Not a single politician, of the current government or opposition has cared to pay us a visit. Ashok Tanwar (state Congress president) once came and promised support, but forgot all about it now.”

Adjacent to the Dalit protesters, Jats are camping for reservations. They say they are tired of government apathy.

In such a backdrop, the Chandralok colony case just adds one more element of complexity to an already simmering caste cauldron that is Jind. The animosity between groups, it seems, keeps growing.