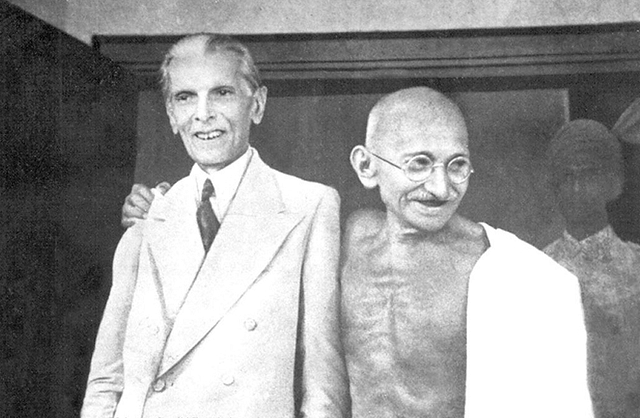

Jinnah And Gandhi Were Human After All

Study some biographies on the Mahatma by writers who have no axe to grind, or his own letters and essays. The halo of greatness around the ‘Father of the Nation’ will disappear.

Why is it that in India questioning an acknowledged political icon is akin to committing a religious blasphemy? Justice Markandey Katju in a recent blog, accused the ‘Father of the Nation’ of acting as a “British agent”. The author alleged that Gandhi, through his actions, often contributed to the weakening of the freedom struggle, leading to a delayed independence as well as the subsequent partitioning of the country. What in any mature democracy would, in all likelihood, have passed off as an aberrant personal opinion, saw a massive furore in the Parliament, with political parties of every hue uniting to condemn it and going so far as to pass a resolution to censure that outspoken gentleman!

Even earlier, when political heavyweights like LK Advani and Jaswant Singh sought to challenge the conventional Indian narrative on MA Jinnah, both were castigated and virtually hounded into political oblivion — not by the Congress, but surprisingly their own party and its affiliates.

It was my incredulity at this that had prompted me to read a biography of Pakistan’s Quaid-e-Azam. For the purpose of neutrality, I searched for one written by someone removed from the subcontinent. I hit upon Jinnah of Pakistan by American historian Stanley Wolpert. I want to share some anecdotes from that book to show how, even though Justice Katju was extreme in his choice of words to describe Gandhi, there was a time through the First World War when Gandhi vociferously espoused the imperial cause and precipitated deliberately the divide with Jinnah.

As per Wolpert’s biography of Jinnah, and some other books, too, by a historic coincidence both Jinnah and Gandhi were in London in 1914 at the start of World War I. The war’s outbreak diverted Gandhi’s ship to London from South Africa and his first message to his countrymen upon arrival was to urge them to volunteer for military service and “Think imperially”. Jinnah himself attended a gala reception for Gandhi at London’s Cecil Hotel but did not participate in the drive of the latter to raise recruits for the army or the Field Ambulance Training Corps.

In November 1914, however, when the Ottoman Caliph opted to link himself with the Central Powers rather than joining the Allies, the Indian Muslim who looked to him as a “deputy of God” saw their loyalties severely challenged. British intelligence agencies feared that the Nizam of Hyderabad might possibly orchestrate a South Asian pan-Islamic revolt. This apprehension never came true and virtually every Muslim soldier in the British Indian Army proved “true to his salt”.

In January 1915, Gandhi, having suffered a slight nervous breakdown and finding himself unfit to accompany his ambulance corps to France, returned to India instead. The Gujarati Society (Gurjar Sabha) led by Jinnah organised a garden party to welcome him. Gandhi’s response to Jinnah’s urbane welcome was to announce to the gathering that he was “glad to find a Mahomedan not only belonging to his region’s Sabha, but chairing it.”

As Wolpert notes, “Gandhi could not have contrived a more cleverly patronising barb, for he was not actually insulting Jinnah, after all, just informing everyone of his minority religious identity.” He goes on to point out the oddity of Gandhi singling out for comment the religious affiliation of a multifaceted man whose dress, behaviour, speech and manner totally belied any resemblance to his co-religionists.

In fact, Jinnah hoped — by his Anglophile appearance, secular wit and wisdom — to convince the Hindu majority of colleagues and countrymen that he was as qualified as Gokhale, Wedderburn or Dadabhai to lead any of their organisations, and yet the very first public utterance that Gandhi made about him in India was to single him out as a “Mahomeden”.

According to Jinnah’s biographer, this very interaction set the tone of Jinnah’s relationship with Gandhi which, in his words, was “always at odds with deep tensions and mistrust underlying its superficially polite manners, never friendly, never cordial… it was as if, subconsciously they recognised one another as natural enemies, rivals for national power, popularity and charismatic control of their audiences.”

The British Government had, as a precautionary measure, put Maulana Mohammed Ali of the Muslim League and his brother Shaukat Ali under house arrest by invoking its martial emergency powers in 1915. The newspapers they edited, Comrade and Hamdard, had argued favourably on behalf of the Caliph of the Ottoman Empire. The Ali brothers became a rallying cry, not just for Muslims but for Hindus as well, and were singled out by Gandhi as his first great national cause in opposition to the British Raj.

While Gandhi courted popular Muslim support by allying himself most outspokenly with the struggle on behalf of the Ali brothers, he sought simultaneously, and won, official confidence by urging all Indians to enlist in the British Army. Both positions, writes the author, appeared paradoxical to disciples who had never considered the Mahatma enamoured with either Muslims or the war and yet, in late 1917 and all of 1918, these very causes proved to be Gandhi’s most important springboards to power. One can contrast Gandhi’s stance at this juncture with that of Jinnah who was most vocal in his criticism of Britain’s intensified recruitment drive insisting that all Indians “should be put on the same footing as the European British subjects” before being asked to fight and thereby earned Chelmsford’s angry rebuke.

The Delhi war conference in April 1918 provided the first battleground on which Jinnah found himself pitted against a half naked man, seated across the Viceroy’s conference table and who was to become his foremost contender for national prominence and power. Gandhi could not conscionably abandon his Muslim cause and participate in a conference that excluded the Ali brothers. He wrote to the Viceroy to explain his hesitation. Lord Chelmsford thereafter invited Gandhi to discuss the issue and the latter, after prolonged discussions with the Viceroy and his Private Secretary, agreed to take part in the conference. The Mahatma’s ‘part’ in that conference, reports Wolpert, was to be confined to seconding the key resolution on recruiting Indians for the army and as regards the Muslim demands; Gandhi was to write a separate letter to the Viceroy.

Having capitulated so completely to the Viceroy, however, the Mahatma was so conscious stricken at what he had agreed to, that he resolved to do it as briefly as possible. In fact, in one short sentence: “With a full sense of my responsibility I beg to support the resolution”! He delivered that sentence first in Hindi and then translated it himself into English. Recounting that event a decade later in his autobiography, Gandhi facetiously chose to focus on the fact that he spoke in Hindi, not on the import of the actual words he spoke or of the meaningful support they rendered to martial violence and the British war machine. Unable to admit how wretched he felt at receiving the congratulations of so many imperialists for having abandoned non-violence to curry favour with a viceroy, Gandhi turned his words around and committed them — in his autobiography written a full decade later — to his own memory and the world.

Gandhi’s sense of outrage on being congratulated on being the first at using the national language, Hindustani, in a Viceregal meeting, when in fact there was no taboo against using it, was surprising. He “felt like shrinking “ into himself!

Jinnah, on the contrary, pursued a nationalist, anti-recruitment agenda insisting that they, the Indian leaders, could not ask their youth to fight for principles, the application of which was denied to their own country. If India was expected to make sacrifices in defence of the Empire, it ought to be as a partner in it and not a dependency, demanding, “… Let full responsible government be established in India within a definite period to be fixed by statute with the Congress-League scheme as the first stage and a Bill to that effect be introduced into Parliament at once.”

Wolpert surmises that if Gandhi had closed ranks behind Jinnah’s leadership in Delhi in 1918, the latter might have mistrusted him less and, while together they might not have persuaded the British to grant India freedom overnight, they could have certainly accelerated the transfer of power timetable and might even have avoided partition.

While leaders like Tilak and Annie Besant marched shoulder to shoulder with Jinnah in opposing the British, Gandhi’s loyalist stance proved devastating to the nationalist cause. He persisted in trying to get Jinnah to join his drive, writing to him “Seek ye first the recruiting office and everything will be added unto you” — a strange missive from Gandhi that left Jinnah too shocked to even respond.

It was only shortly thereafter that Gandhi was forced to acknowledge the wisdom of Jinnah’s stand on recruiting as soon he started going from village to village in Gujarat accompanied by a soldier with a tin drum. The Mahatma wrote,

“As soon as I set about my task, my eyes were opened. My optimism received a rude shock. We had meetings wherever we went. People did attend, but hardly one or two would offer themselves as recruits. ‘You are a votary of Ahimsa, how can you ask us to take up arms?’ ‘What good has Government done for India to deserve our cooperation?’ These and similar questions used to be put to us.”

By August that year, Gandhi started to withdraw from the recruitment campaign and, before September was over, his health broke down completely. In his words,

“I very nearly ruined my constitution during the recruiting campaign. I felt that the illness was bound to be prolonged and possibly fatal…Whilst I was thus tossing on a bed of pain… Vallabhbhai brought the news that Germany had been completely defeated and that the Commissioner had sent word that recruiting was no longer necessary. The news that I had no longer to worry myself about recruiting came as a great relief……I passed the night without sleep. The morning broke without death coming. But I could not get rid of the feeling that the end was near.”

My intention in bringing into the public domain these accounts of the early years of Gandhi’s political career in India is neither to disparage the Mahatma, nor to eulogise the much reviled Jinnah. I have seen the fate of those in this country who have attempted either of those foolhardy tasks. My limited brief is to show that both the ‘saint’ and the ‘demon’ were very human — with the same ambitions, jealousies and frailties that make and mar the rest of us.

At a time when Gandhi needed to establish himself politically in India, his prime contender for the centre-stage was Jinnah. He chose to counter Jinnah’s anti-government stance by positioning himself as a loyalist of the crown, even though recruiting troops for the British was working at cross purposes with his own ideal of ahimsa. He waded into the Khilafat Movement (movement for the Caliphate) solely to counter Jinnah and the Muslim League’s primacy in espousing the Muslim cause, and yet when it came to dealing with the ‘secular’ Jinnah, the astute Gandhi wasted no time as pointing him out as an outsider, a “Mahomedan”, to a largely Hindu gathering.

Jinnah responded in kind with thinly a disguised hatred, and over the years both leaders sparred till they settled into their own intractable corners, delaying independence by, God knows, how many years and leading finally to the horrific Partition of the country. Had these two individuals not been guided by their narrow self-interests and developed such deep mistrust and personal animosity at the very start, the history of the subcontinent could well have been something different.