Long Read: Why Amaravati May Not Be The Best Place To Build A Capital City

Building Amaravati was former chief minister Chandrababu Naidu’s dream — a legacy he wanted to leave behind. But had he heeded to sound advice?

An oft-repeated reference is made to the Sivaramakrishnan Committee report, which had found Amaravati “not suitable” for being made into the capital city. Swarajya examined the report and found it path-breaking in terms of analysis and suggestions.

The last few days have witnessed speculations over the fate of Andhra Pradesh’s (AP’s) capital city, Amaravati.

Municipal Administration Minister Botsa Satyanarayana’s statements about the area being flood-prone and requiring almost double the construction costs have raised doubts about the YSRC (YSR Congress) government’s stand on the capital city.

TDP (Telugu Desam Party) has gone so far as to accuse the Jagan government of flooding the city deliberately to make it an issue to relocate the capital.

The YSRC government has maintained that a thorough review is being done on the issue and an announcement would be made soon.

An oft-repeated reference is made to the Sivaramakrishnan Committee report, which had found Amaravati “not suitable” for being made into a capital city. Swarajya examined the report and found it path-breaking in terms of analysis and suggestions.

But first, a little bit of the ‘Blockbuster’ background story.

Amaravati, Amaravati! There’s No City Like Amaravati!

Amaravati had elements of a Bhansali-like period movie: grandeur and grandiosity writ large across all aspects — the scale, the vision, the finances, the name itself. The cast had big names — the world’s leading architect, Norman Foster, the World Bank, AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank), and Singapore-Surbana Jurong.

Reports in the earlier years had it that the then chief minister, Chandrababu Naidu, had set his heart on a capital that “would reflect Telugu culture and history”.

There were several meetings with historians, even film makers and set designers, so that the architects Foster and Partners of United Kingdom (UK) were able to satisfactorily incorporate elements of heritage and history into the design of the buildings.

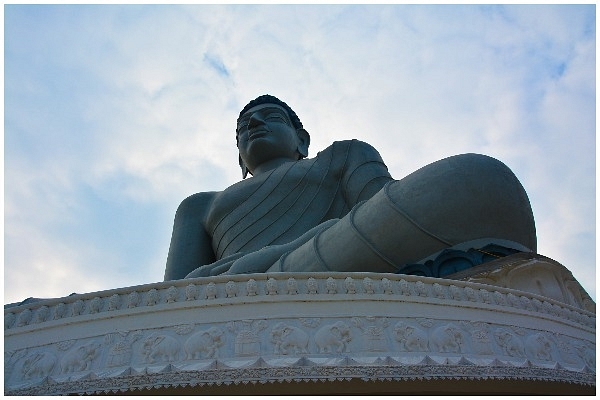

The original Amaravathi — around 35 km away from the planned, new Amaravati — had been the capital of the Satavahana kings from around the 3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE.

Later it was also a Buddhist site. With a strong desire to be “remembered for what he had done”, Naidu wanted a world-class city and also a people’s city. The latter was achieved symbolically by bringing soil and water from all areas in the state, for the consecration ceremony.

At the other end of the spectrum, Amaravati was also set to be dotted with towering structures, glass facades, a central boulevard, wide avenues and footpaths, a metro and riverway transport. Roads and flood mitigation and sewerage systems, a green city, solar energy, electric vehicles, cycle routes were all part of the works.

This world-class city required funds to the tune of Rs 1.08 lakh crore. Hence, funding came from the World Bank, AIIB and others, apart from the central government component of Rs 5000 crore.

The “World-Class”, “Sustainable”, “People’s Capital City”... That Wasn’t.

The World Bank had in fact, termed it as “Amaravati Sustainable City Development Project”. When the World Bank — and close on its heels, AIIB — withdrew from the capital-city story, there were a series of allegations, theories and doomsday prophecies.

But is it really the tragedy that it is being made out to be?

Some people’s dreams of having their very own “Detroit” or Singapore in their state may not have come true, but it has been almost a lifesaving development for the state.

Fact is, Amaravati was being built at considerable risk – ecological, financial and social. Ironically, despite the nomenclature, “sustainable” was the one thing it wasn’t.

Despite claims of the state government and the APCRDA (Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority) of this being the largest “successful land-pooling scheme”, Amaravati’s farmers — save some — were unhappy parting with their lands, and indignant when they were coerced into selling it away.

Their insecurities resulted in their easy galvanization into pressure groups.

Beginning October 2016, World Bank’s Inspection Panel (an independent complaints mechanism for people and communities who believe that they have been, or are likely to be, adversely affected by a World Bank-funded project) had been receiving requests from farmers for inspection into the project, citing harm to their livelihood, environment and resettlement.

People felt that the “People’s City” wouldn’t even run, let alone being a happy place, because it wouldn’t be able to sustain its daily business of living, with an imported lifestyle superimposed on the original lifestyle of a vast numbers of people. Besides lands and livelihood, even community dynamics would go for a toss, they felt.

The social-sustainability factor was amiss, even for government officials, who — despite the lavish residences being built for them — were loathe to move into a new city.

Most cities evolve organically as employment and amenities and facilities are guaranteed. Amaravati was a primarily rural, agricultural area, to be converted into a mega city, where livability was a major concern.

On top of it all, there was ecological unsustainability — being a flood-prone area and falling within a seismic zone.

And finally, financially, it was a daring act. The total estimated cost of the Amaravati capital city project was Rs 1.08 lakh crore. Of this, the World Bank and the AIIB aid amounted to just Rs 3,600 crore. The Centre had chipped in with Rs 2,500 crore, though some more was expected later.

Andhra Pradesh’s finances were already an acknowledged mess. Jaganmohan Reddy’s white paper on state finances estimated an outstanding debt of Rs 2.58 lakh crore.

Contrary to Naidu’s current claims that the World Bank loan was at low interest rates, at that time, the state government officials had said that they were “pursuing it despite the above concerns, and in spite of the high interest rate that the World Bank loan came with, at 8-11 per cent. This was because, as per the agreement on external aid, the Centre would pay 30 per cent of the amount, which would take care of the upfront money.”

Of Jagan Redeeming Himself, And Sustainable Capital Solutions

Jagan’s intentions are being questioned; there’s talk about “public projects being dependent on the whims of politicians” and there’s a serious possibility of discontent among various categories of people.

In this context, it is worthwhile to delve into the report of the Expert Committee that had been appointed in 2014 to, “Study the Alternatives for a New Capital for the State of Andhra Pradesh”

This report, commonly known as the `Sivaramakrishnan Committee report’ was a comprehensive approach to building a World-class Andhra Pradesh, first because it consisted of topmost officials from organizations like the Centre for Policy Research, School of Planning and Architecture, Indian Institute of Human Settlements, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, and National Institute of Urban Affairs.

And second, the terms of reference included, among other things, least possible dislocation to existing agricultural systems, preservation of local ecology, promoting environmentally-sustainable growth, vulnerability assessment from natural disasters, minimizing the cost of construction and acquisition of land, etc.

Given this, adhering to their suggestions may be the most “sustainable” way to go about building a ‘capital city’.

Suggestions In The Sivaramakrishnan Committee Report

The Expert Committee approached options, not just for building a “world-class” capital city, but for the development of the new state of AP. A strategy that would enable development of towns and smaller areas, so that employment opportunities for the 51-million additional workforce by 2051 was created.

Significantly, it went even beyond laying down a roadmap for development — it talked about how AP, by realizing its potential, could be a powerhouse on India’s eastern coastline.

For the capital city, the Committee studied options of a) Greenfield location in which a single super city is created, b) expanding existing cities, and c) distributed development.

Why Not Amaravati?

The Committee had several concerns about concentrating government functions within the Vijayawada-Guntur-Tenali- Mangalagiri (VGTM) urban area — where Amaravati currently is, and which the state government was then most keen on.

It felt that though this area had geographic centrality, that was not an essential requirement: states like Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal do not have this centrality.

There was a major concern about losing the best agricultural lands in the country in the process, as Krishna, Guntur and West Godavari districts form the `rice bowl’ of the country.

Also, it would lead to unemployment because, for instance, 65 per cent people in Guntur and 56 per cent in Krishna district are cultivators and agricultural laborers. They would be displaced if the lands on the proposed ‘Ring Road’ were converted to non-agricultural use. Small holdings would disappear and so would farmers.

Real estate operators would be the only beneficiaries, whose profits would surge from speculation related to land. This warning of the Committee has indeed been witnessed: land prices soared artificially — on only the promise of future development, rather than any real increase in the worth of the land.

“The present development plan for the VGTM area with its Ring Road seeks to bring more land under urbanization… and this would have serious economic consequences (Unlike in Hyderabad where irrigated agricultural land was not an issue)...”

Moreover, locating government offices and institutions within the Vijayawada-Guntur urban area may lead to a construction boom and haphazard development, which may seriously strain the existing infrastructure including water supply, sewerage and roads, which were already showing some stress.

The Committee cited findings of the Geological Survey of India: that a seismic micro-zonation had highlighted the problem of high water table and vulnerable soil types, which together may lead to severe problems of foundations and soil bearing capacities.

Reportedly, this was one of the reasons there weren’t many high-rise buildings in this area.

Yet, what has been witnessed is in total contrast to the cautionary advice of the Expert Committee. APCRDA’s major works began with lavish residences for legislators and gazetted and non-gazetted officers in several high-rise building complexes. This was in total contrast to the caution advised by the Expert Committee.

Having studied the history of new-capital-city development across the world, the Committee had realized that:

a) the average period of development of the capital city ranges from 6 to 20 years; and

b) for a greenfield city, a critical mass of 0.5-1 million population is reached only after 20-30 years of the initial development period.

This meant a period of 40-50 years from conception. The Committee warned that Andhra Pradesh “needed to be very cautious about large-scale greenfield development”, to avoid multi-decade gestation periods, and instead build on existing urban areas.

The Committee also warned about the “completely unrealistic articulation of capital investments”. At 10-30 times the investments made in similar projects in India, these were unthinkable — given the economic status of the state and the fiscal challenges of the central government.

Path-breaking Solution: Several Capital zones

The Committee’s path-breaking suggestion was about having several capital zones, rather than one single capital city, which, it said, was “not a feasible option available to Andhra Pradesh” because of the large-scale land acquisition involved.

Government offices could be spaced across the state in several different centres. Distances need not be a deterrent, given that the erstwhile united AP, under chief minister Naidu, had set an example in overcoming geographical distance by modern, electronic communication.

To facilitate this further, the rail and road connectivity between different cities could be improved and expanded.

Distributed, Decentralized Development

Following the ‘terms of reference’ given by the centre, and the considerations of distributed development for the state, the Committee had built a model of decentralized development.

Within the VGTM area, if the criteria of centrality and access had to be satisfied, “accommodating a limited number of governmental offices” would suffice. Jagan’s rethink regarding restricting capital city to five administrative buildings adheres to this suggestion.

`Distributed development’ would mean that capital functions are spread across three regions, in this manner :

- Vizag in Uttarandhra, already regarded as a centre of Heavy Industry, ports and technical institutions could have government offices dealing with industry, manufacture, ports, shipping, petrochemicals.

- Rayalaseema comprising Kurnool, Anantapur, Tirupathi, Kadapa and Chittoor, being already a part of the golden quadrilateral, would be a part of high-capacity transport corridor — but first, their problems of water and power supply had to be corrected.

- And finally the `Kalahasti spine’ had the potential for greenfield development.

Departments related to Animal Husbandry, Fisheries, Agriculture and Industry, Mines and Minerals and Accounts could, instead of being with the Chief Minister’s office, be located close to areas which they service.

Consequently, all IT and industry-related departments could be in Vizag, agriculture-related departments in Prakasam, animal husbandry in Ongole, education in Anantapur, health in Nellore, irrigation in Nellore and welfare in Kadapa.

Districts and Capital Zone Suitability Index

The Committee scored districts in AP using five criteria — after reviewing the experience of other capital-city development projects in India and abroad (Indian Institute for Human Settlements, 2014) — namely, water, risk, connectivity, land availability, and regional development.

A ‘District Suitability’ index was computed and based on that, three clusters of districts emerged as highly suitable — Krishna and Guntur (main cities — Vijayawada and Guntur); Visakhapatnam and East Godavari (main cities — Visakhapatnam and Kakinada ) and Nellore (main city — Nellore).

Andhra Pradesh As A Significant Economic Entity In The Bay Of Bengal

The Expert Committee pointed out how, if fiscal prudence is combined with carefully chosen investments, along with policy and implementation coordination, Andhra Pradesh could become the primary zone along the eastern coast for international and domestic trade, energy (thermal and renewable) and manufacturing.

It could provide significant competition to neighboring countries.

For instance, developing deep-water ports along with efficient bulk-cargo and container traffic movement can make it a maritime and trans-shipment destination.

If gas and renewable-led energy infrastructure is developed, along with dedicated freight corridors, we can give competition to Thailand and Malaysia as a manufacturing hub for Japanese, Korean, European and US transnational supply chains.

The Andhra Diaspora, the Committee felt, could facilitate this process through skills and investment — especially in the deployment of technology, IT, health and knowledge infrastructure — in various parts of the state.

At the time of publication, the Andhra Chief Minister had not given an official statement on the fate of the proposed capital. This decision may just be the most important one that Chief Minister Jagan Reddy takes in his political career.

Has it come too early for comfort?

(An earlier version of this article had a reference to the total estimated cost of Amaravati capital city project in dollar figures. This has now been changed to Indian rupees.)