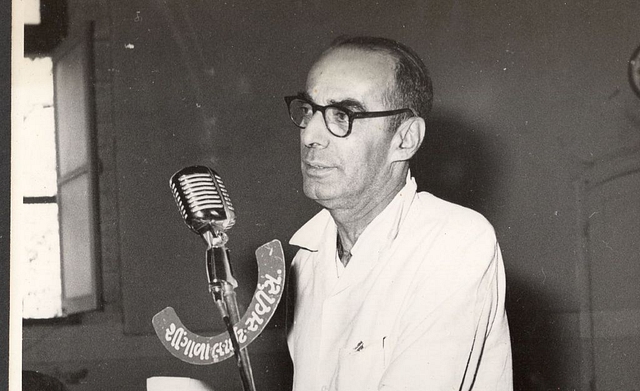

Masani At 110: Perhaps More Relevant Today Than Ever

Is India inherently a secular nation? Here’s an answer from one of India’s leading liberal politicians, a highly-Westernised, not-very-orthodox Parsi gentleman, the late Minocher (Minoo) Rustom Masani:

“In fact, there is no country less secular than India. Supporters of all religions are devotedly so to the extent that some of them are prepared to kill those who adhere to other religions for no other offense. Most of our holidays are not secular.”

This is a quotation carried in the March-June 1993 issue of Freedom First, a magazine he founded in 1952.

And what about the Indian Constitution – is that secular? Here’s what Masani (a member of the Constituent Assembly), wrote in a 1988 article, “India – Time for a Renaissance”:

“. . . the Indian Constitution is pro-religion. It is not secular. The word which was smuggled into the Constitution by Indira Gandhi is wrong.”

It is worthwhile remembering Masani on his 110th birth anniversary today, on two contentious issues – the religion-politics equation and state-markets equation – that roil the nation.

Going by the Oxford Dictionary meaning of secularism – anti-religious – Masani said the Constituent Assembly never wanted India to be anti-religious. “We need more religion or dharma in politics”. But that did not mean pandering to religious groups for the sake of votes – whether it was the Muslim Women’s Bill (he wanted someone to challenge it in court) or the attempt to ban the television serial Tamas, which hardline Hindu groups wanted.

He was also the initiator of the demand, in the Constituent Assembly, for a uniform civil code. Minorities, he wrote in a 1986 article `The Minorities’, have a right to propagate their religion, even convert people, and run their own educational institutions. “But they have no right to demand exemption from any part of the civil and criminal law of the land. That is taking freedom of religion beyond its proper limits.”

What would he have made of what goes in the name of secularism today? Masani was brusquely dismissive of the secular brigade. “There are some silly people who talk of India as a secular state; they talk of secularism when they don’t even know the meaning of the word,” he wrote in the 1988 article. In 1993, he said much the same:

“The use of the word `secular’ by those who do not even understand its meaning is quite nauseating and it is high time we stopped using this term in the present context.”

He believed Jawaharlal Nehru brought the word secular into the lexicon at V. K. Krishna Menon’s suggestion.

But Masani was equally intolerant of majoritarianism. “I do not accept the right of the majority to trample on minorities. . . I don’t believe that Hindus have a right to dominate Muslims because they are in a majority,” he wrote in 1986 and pointed out that he quit as chairman of the Minorities Commission in 1978 because the Morarji Desai government refused to accept that Aligarh Muslim University is a Muslim institution.

The idea of religion as a purely spiritual influence on politics does sound naïve in these times, but perhaps Masani’s preference for the term non-denominational may be more appropriate. He said the government should declare only non-denominational holidays (Republic Day, Independence Day) and make the rest sectional holidays that different faiths could take.

Masani’s active engagement with the secularism debate came much after he retired from active politics in 1971 after resigning as president of the Swatantra Party. His main battle from the 1950s till his death in 1998 was against Nehruvian socialism and the totalitarian version that Indira Gandhi implemented.

Masani was a Marxist in his younger days and his deep revulsion for communism came from his disillusionment after the Stalinist excesses in the Soviet Union. Masani’s answer to socialism was what he called a mixed economy, which would have three sectors – a very small sector of existing industries which could be nationalised (this would extend only to exceptional cases), a public enterprises sector (new industries in areas where the private sector was unable to invest) and free enterprise which would be the largest segment.

But when he found that Nehru – his one-time close friend and ideological companion – was not even travelling this middle path and was pushing for state socialism, he lost no time in raising the banner of revolt. Even before he teamed up with Rajaji to start the Swatantra Party in 1959, he had started the Democratic Research Service with the blessings of Sardar Patel to spread word about subversive communist activities in Telengana, the Indian Committee for Cultural Freedom to combat Soviet propaganda, and Freedom First to propagate liberal values.

Along with Rajaji, Masani was one of the original articulators of the idea of minimum government in India. Government, he said, should be small and strong – concentrating on defence, law and order, justice, infrastructure, education. So, minimum government does not mean the government withdrawing from the social sector, as the anti-reformers insist. And Narendra Modi should bone up on Masani’s writings to know that minimum government isn’t merely about e-governance and scything processes; it is much more.

Masani believed a big state was the inevitable result of people constantly looking to politicians to change things. “Every time the government’s powers are enlarged, more things can be done by `them’ to `us’,” he wrote in a 1969 article in which he also warned against the `we’ versus `they’ phenomenon of people blaming politicians for all the ills of the country. Both in this and the 1988 article, he exhorted people to change themselves and become active citizens. “The daily exercise of vigilance is the price of liberty,” he wrote in the 1969 essay. A year earlier, he had launched the Leslie Sawhny Programme of Training for Democracy, which attempted to inculcate the value of active citizenship in young people.

On this wise Indian’s birth anniversary, as political contests are increasingly revolving around personalities, as people blindly expect a Narendra Modi or an Arvind Kejriwal or a Nitish Kumar to deliver the goods for them, it would be useful to internalise Masani’s words – “I think the country can advance inspite of the government . . . Let us get going. We are a good, clever and intelligent people.”