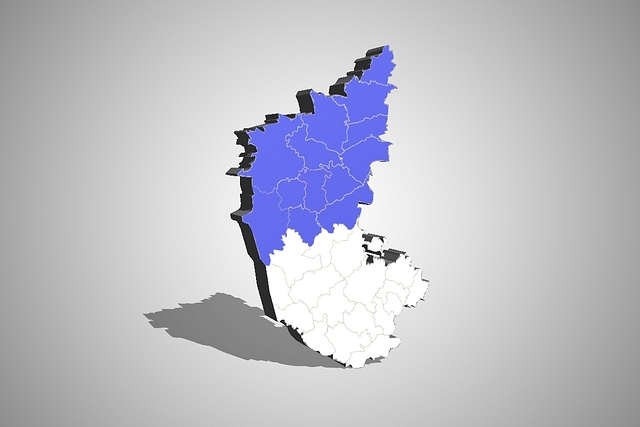

North Karnataka: The Tyranny Of Distance And Discrimination

North Karnataka trails other regions in important areas such as health, education and industrial and social development.

It’s time for the centre to step in and set things right.

I was born in Bidar, the crown tip of Karnataka, and which is called the Punjab of Karnataka – the reasons being this city has five rivers flowing through it; it is home to Nanak Jhira, the birth place of Bhai Sahib Singh one of the Panj Pyare (one of the five beloved ones), and has a significantly higher Sikh population compared to the rest of Karnataka. There ends the similarity.

Bidar, even today, is amongst the most backward districts of the state and none of the development indices (human, social, economic, educational and industrial) are comparable to the developed districts of the Old Mysore Region (OMR).

Growing up here, the only constant in our lives and that of the majority of people in North Karnataka was migration – in search of a better future. I was lucky as in one such village my family migrated to (my extended family lives there to this day), and where I went to school, the schoolmaster noticed that I was good at maths and had a good memory. He pushed my father to migrate to Bengaluru for my education and everything changed after that.

Bengaluru was manna to us. It gave us (and all those who migrated) opportunities that we did not have in our region due to the discrimination practised against North Karnataka by the powers that be in Bangalore probably due to the ‘tyranny of distance’.

The question, however, is: has the ‘tyranny of discrimination’ against North Karnataka decreased and evanesced in the last 30 plus years?

To eschew my own native bias arising out of past experience, I have tried to factor in development attributes such as health care delivery, education facilities, employability after education, jobs availability, industry and infrastructure investment, to analyse the tyranny of discrimination. I have steered clear of human development indices as they take time to change albeit any improvement made to the quality of life.

For proper assessment of the typology of development, it is important to study not just the quantitative change in the last three decades in North Karnataka but also the qualitative aspects of development. This is reflected in the level of technology use in the everyday life of the common man in addition to health and nutrition, individual sanitation, ease of living parameters like access to uninterrupted electricity, access to good roads and means of safe transportation in comparison to their OMR compatriots.

Healthcare

Some interesting factors sampled were: The number of people who are sick and need health care support: In OMR it was 95 to 98 per 1,000 while in North Karnataka it was 95 to 102 per 1,000. The problem area was Yadgir, which did not have even a decent secondary health centre and people had to go all the way to Kalburgi or Raichur for something as common as assisted delivery in complicated obstetric cases, but which is a facility taken for granted in OMR. Doctors said more nutritional and geriatric issues were prevalent in the districts of North Karnataka than the OMR. Almost 90 per cent of people of North Karnataka have to travel more than 100 kilometres when in need of tertiary care, resulting in loss of income, while the comparative figure for the OMR region stood at 57 per cent.

Out of pocket expenditure: OMR being relatively developed, the penetration of insurance, Employees’ State Insurance and public-funded insurance programmes and others are significantly higher. Bidar, Gulbarga, Raichur, Yadgir, Chitradurga, Bellary, Koppal , Karwar, Chikkamagalur, Bijapur have a woefully low penetration in the areas of individual/family insurance. The comparative per capita reach of public-funded insurance is poor as people are not aware of such programmes. Upon sampling in both North Karnataka and OMR, it was found that nearly 40 per cent to 60 per cent of patients are on the verge of catastrophic poverty due to out of pocket healthcare expenses in the districts of North Karnataka verses OMR. Individual/family private insurance penetration was nearly 25 per cent in OMR and nearly 40 per cent in the urban areas of Bengaluru, Mysore and Mangalore compared to 0.6 per cent in Yadgir, 1 per cent in Koppal to 3 per cent in Bellary. Need I say more?

State expenditure in health care: The Karnataka government at 3.8 per cent of its aggregate expenditure spends the least for healthcare among all southern states of India. Even among this, the amount spent for healthcare facilities in the three districts of Bengaluru, Mysore and Mangalore exceeds the combined expenditure of the rest of the districts. All the state-owned tertiary health centres are concentrated in these three districts. The recent addition of Jayadeva Hospital branches in Raichur is just an ornamental measure as doctors and specialist staff visit such centres just once in a month. Karnataka needs to take responsibility and open centres of excellence in healthcare in the districts lacking in such an important service.

Percentage Of Girls Married Before 18

This aspect was found to be a credible indicator of overall quality of life index. Families with access to remunerative employment, education and insurance invariably got their daughters married after they received some education while poor families looked at girl children as a burden and got them married early. Girls who married early gave birth to unhealthy babies with the family remaining less educated and poor with hardly any access to health services and government programmes compared to girls married at a suitable age.

It would be surprising to know that nearly 35 per cent of girls were married before they reach the age of 18 in all districts of North Karnataka. In OMR, the figure was between 6 per cent (Mangalore and Bangalore urban) and 21 per cent in different districts except Chamarajanagar, which was 35 per cent. This index alone is a conclusive evidence of the tyranny of discrimination and continuous neglect which North Karnataka has faced till now.

Education

Both the quality and number of educational institutions in North Karnataka are poor as compared to that in OMR. Bengaluru with its IIM, IISc and various centres of excellence attracts talent and retains them as compared to, say, a Bijapur or Gulbarga. The government on its part has never made any attempt to bridge the gap in education resources for the people of North Karnataka, again proving the existence of the “tyranny of discrimination”.

Employment After Education

In a survey among private industries in Bengaluru, it was evident that a student who has studied in OMR has higher chances of landing a job as compared to someone who has studied in, say, a districts like Koppal, Bidar etc, with an equivalent degree. Employment in semiskilled and unskilled blue collar jobs does not subscribe to this discrimination.

Employment Opportunities In North Karnataka

In a survey conducted among family members, extended family members and their friends and families, which included 316 youth, it was found that 276 youngsters had moved to Bengaluru in search of jobs, six to Mysore, two to Belgavi; seven went abroad for further education; eight to Mumbai, 13 to Chennai, four to Delhi to prepare for the Indian Administrative Service examination. None of the youngsters stayed back in their native districts. This is the stark truth about the state of affairs as far as employment opportunities are concerned. That places like Hubli, Belgavi themselves are victims of this situation should serve as a wake-up call for the powers at Bangalore.

Industry And Investment

Since this area alone requires an expansive treatment and is beyond the scope of this article, I will try to summarise it in terms of industrial output. All the districts of North Karnataka contribute less than 1 per cent to the industrial output compared to OMR. Bengaluru alone generates nearly 90 times the output of all north districts combined. This includes state and national public sector undertakings (PSUs) and private enterprises. Information Technology and Biotechnology which have ministries to run their affairs have near zero output outside of OMR. All the districts of North Karnataka can be classified as industrially backward. Some like Koppal, Yadgir and Bidar do not have any industry at all. The state government appears least concerned about industrialisation of these areas.

Asset Index

As a proxy for wealth, an asset index was constructed using information about household characteristics including source of lighting, source of energy for cooking, source of drinking water and type of toilets. This index was used as a common control variable. Applying asset index to households across Karnataka, it was found that OMR households are nearly three times asset rich compared to households of North Karnataka.

Some very broad socio-demographic and economic statistics of importance were considered too. There is a significant 12 per cent increase in monthly per capita consumption expenditures of the households over the last 10 years even in the districts of North Karnataka. There is also a big improvement in the literacy rates with a massive decline in the percentage of illiteracy from 42 per cent to 31.5 per cent over the last 10 years. Directly, from a health viewpoint, it is also important to note that significantly more number of households gained access to toilets over this decade in India. This number has risen sharply after 2014 when the Swachch Bharat Abhiyaan (Clean India Mission) was launched across the country. The other major development in this timeframe has been the rapid expansion of health insurance cover in the country; hopefully Ayushman Bharat changes the dire state of healthcare in North Karnataka. One common issue is lack of information. Many people are not aware of the coverage they are entitled to and how they can benefit from insurance.

As said earlier, good quantitative changes did take place in the last few decades in North Karnataka. The typological assessment of development, however, revealed that the OMR region is far ahead of districts of North Karnataka in areas like use of technology in everyday life by common man, health and nutrition, individual sanitation, ease of living parameters like access to uninterrupted electricity, access to good roads and safe transportation. These factors are evident to the common citizens too, and which has led to a feeling of resentment against the state government.

The other important issue was the concentration of government departments, central and state PSUs in OMR. Starting from agriculture to industry to water and sanitation, all are situated in Bengaluru or OMR. The bureaucrats have to be posted in areas where they are needed the most. For instance, what is the use of the Karnataka Water Development Board working out of Bengaluru when the requirement for water is acute in arid areas of North Karnataka? Why should Karnataka Industry Development Board sit in Bengaluru and why shouldn’t it be relocated to, say, Koppal where industry needs to be developed? About 99.9 per cent of government offices, boards and PSUs are in OMR.

From this analysis, it can be concluded that North Karnataka continues to face severe discrimination. The situation needs to be addressed immediately to stop further deterioration and stop an acrimonious battle for separate statehood.

I hope the central state government takes some serious initiatives in improving the quality of life of the people of North Karnataka.