Odisha’s Journey To The Bottom: Commodity Bust Hastened The Fall

Why has Odisha lagged behind on development in recent years?

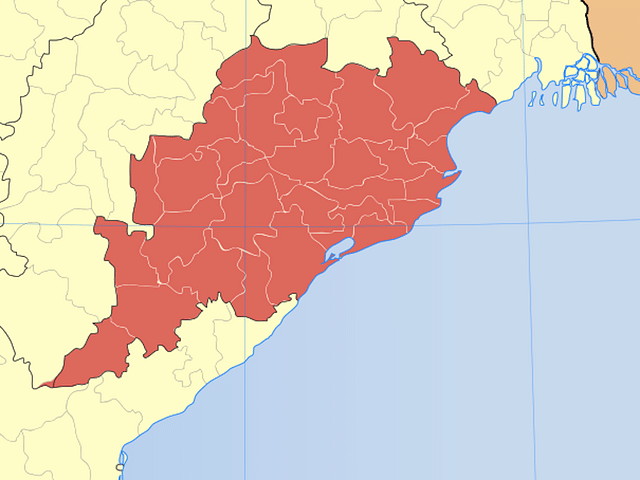

In 2015, Odisha was once again overtaken by Madhya Pradesh with respect to per capita GDP after remaining ahead of the latter for nearly ten years. This was because Odisha has been one of the slowest-growing major states of the last six years, with only Punjab and Chhattisgarh competing for the wooden spoon. Contrast this to the period 2004-09, when Odisha was in the top five, enabling it to move up the ranks on per capita GDP at the national level. The relatively slow growth is compounded by the fact that Odisha has the second highest consumer inflation (amongst major states) in the country over the last three years, with only Chhattisgarh seeing higher consumer inflation. The combined effect of both these factors is the slowdown in the pace at which the state is eliminating poverty.

Odisha’s downward trend coincided with the slowdown in global commodity prices as mining forms a significant proportion of its GDP, and commodity prices have seen a dramatic fall since 2009.

Odisha is dependent on revenues from bauxite and iron ore. Aluminium prices are down by more than half from their peak in 2008 while iron ore prices are down by nearly four times from their peak in 2010. In some ways this is similar to the troubles of oil-producing nations today.

However, a closer inspection suggests that Odisha’s mining problems are only one part of a larger problem of governance. Whether it is agriculture or education or the general levels of corruption, the state is heading towards the bottom.

Agriculture

Odisha’s agricultural domestic product grew by a total of 26 percent between 2005 and 2014. India on an average grew by 41 percent, and MP grew by an astonishing 223 percent. One of the biggest reasons for the agricultural revolution in MP was the rapid expansion of irrigation. Between the two agriculture censuses of 2006 and 2011, MP’s irrigation area expanded by a massive 26 percent while Odisha’s expanded by just 6 percent. Now, Odisha receives nearly twice the amount of rainfall as MP while its irrigation coverage is at about 26 percent (2011 Agriculture census) while MP’s is at 38 percent.

Now here is the problem: if one looks at the capital expenditure allocations in the budget for that period, MP spent less than Rs 1 lakh for every additional hectare of land irrigated, but Odisha spent more than Rs 9 lakh for the same size of additional area irrigated. The reason for this difference is the excessive focus on building canals in Odisha while MP is more dependent on micro-irrigation. Odisha’s allocations and strategies for providing electricity to farmers is also quite abysmal leading to very few farmers benefiting from the so-called power surplus in the state.

There may be a variety of reasons for these differences – small sizes of landholdings, Odisha facing floods and cyclones, large parts of the state being mountainous, food consumption habits, etc.

However, in my view the biggest difference between MP and Odisha is the leadership. Naveen Patnaik, son of the legendary pilot and politician Biju Patnaik, was educated in Doon School and then spent a long time writing and away from politics. Shivraj Chouhan, the BJP Chief Minister of MP, on the other hand was born in rural MP and then worked his way up through the political hierarchy. What is impressive is the amount of time he had spent on rural and agricultural issues while in Parliament between 1996 and 2003. Naveen, on the other hand, depends a lot more on bureaucrats who are somehow not convinced that the state can have an impact on agriculture.

The mindset of the state government is visible in this comment by the Industry Secretary:

“Agriculture has limited potential to add to our Gross State Domestic Product (GDP). So, development has to come from the manufacturing sector”

Education

It isn’t a coincidence that three of the slowest major state economies in the country – Odisha, Chhattisgarh and Punjab – also have large populations of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. If both agriculture and industry of these states get into trouble, the economy would tend to struggle because services typically need higher education levels and across the country education levels amongst SC/STs are quite low.

In Odisha for example, one in three tribals in the 15-24 age group is not even literate (tribals make up a fifth of the population). On mean years in schooling, Odisha is among the bottom five. While only 7 percent of the 20-24 age group are graduates (India is at 12 percent), the situation is worse among SC/STs, where only 3 percent and 1 percent respectively are graduates. Given the SC/STs form nearly 40 percent of the population, most of the manpower is ill-prepared to deal with the requirements of a modern economy.

It is not due to lack of effort through. Odisha spent 14 percent of its revenue expenditure on education in 2005 and this went up to 18 percent in 2014-15. Therefore, while the share of budgetary allocations has increased substantially since 2005, the outcomes are still not satisfactory when compared with the national picture. The only positive is that the state does quite well on ITI-trained workers, the only downside being that with the slowdown in manufacturing, jobs are far and few.

The lack of education and lack of jobs for skilled workers means that Odisha along with Bihar and eastern UP produces large numbers of cheap skilled and unskilled labour for the rest of the country

The Many Scams

There have been two major scams during Naveen Patnaik’s tenure – The mining scam and the chit fund scam. The mining scam was valued at about Rs 59,000 crore and involved numerous politicians, bureaucrats and business people, both from inside and outside the state. While some licences were cancelled, none of the powerful amongst the accused have been prosecuted till date.

The chit fund scam in Odisha is said to have involved top politicians, bureaucrats and business people. Some of Patnaik’s party men were found to be involved in it as well and at least two BJD MLAs have been arrested till date.

One of the reasons Patnaik has been preferred by many voters is that none of the corruption scandals has ever touched him. Also, he sacks least three ministers on an average every year for a variety of reasons, including corruption. The constant shuffling of ministers means that much of the control remains with the CM and a group of loyal bureaucrats, which makes it very similar to the coterie that operated around Rajiv Gandhi.

The high incidence of corruption puts humongous wealth in the hands of a limited few, which is evidenced by the property prices in Bhubaneswar. This had led to the crime rate in the state growing at a much faster pace than rest of the country between 2010 and 2014 (28 percent versus the India average of 22 percent).

Investments

During the peak of the commodity boom, numerous steel and aluminium players had committed to invest in Odisha. The biggest of these was Korean steel maker Posco. Over a 10-year period, owing to numerous issues, whether related to supply of ore or the acquisition of land required for the plant, the company faced numerous hurdles which finally led it to call off the project last year.

While there are attempts to persuade Posco to invest in Odisha, the incident itself has scared off many investors. The Vedanta plant at Niyamgiri was abandoned when the central government cancelled the permit to mine the range on account of serious pressure from tribals, NGOs and courts.

Consequently, state FDI, which was $149 million in 2009-10, has come down to an average of $25 million over the last five years. Odisha, in any case, was almost at the bottom on the measure of credit-deposit ratio (40 percent) – meaning very little money was being used to create wealth beyond the usual bank deposits.

When the commodity sector boomed, Odisha had an outstanding period with record growth between 2004-09. The dramatic fall in commodity prices exposed the state’s lack of a Plan B as both agriculture and education languished behind national averages. The fact that large investments were made in these sectors with limited or poor results indicate severe challenges in execution within the cabinet as well as the bureaucracy. The corruption scandals and poor investment climate have further exacerbated the negative business and social climate in the state.

The biggest risk for Odisha is that it is one of the few states where the Opposition is significantly fragmented, leaderless and with no possibility of coming together (Congress and BJP). This makes it an easy stomping ground for the BJD in 2019. Even if the BJP were to do much better than in 2014, it may have to rely on the BJD to form the next government. It is these calculations that prompted the BJD to dump BJP in the first place in 2009.

Lastly, Naveen Patnaik has had an unblemished record as a leader and enjoys unparalleled leads over other leaders in Odisha. Unless the opposition is able to aggressively diminish this image or put forth a candidate of equal stature, the Naveen regime could last all the way to 2024. In some ways, Odisha is already heading the Bengal way with the unparalleled dominance of one leader and one party and an economy that is struggling at the bottom.