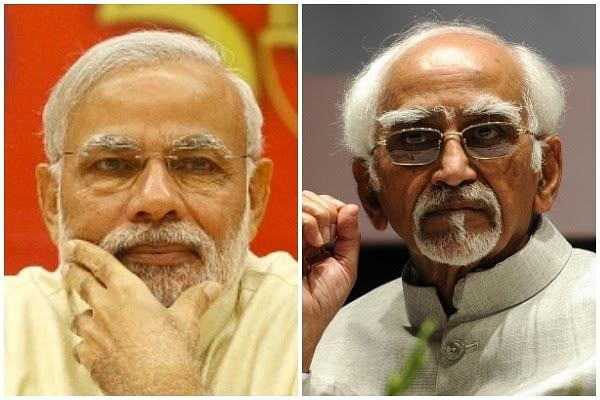

Prime Minister Modi Did Well To Indirectly Call Out Hamid Ansari’s Views As Minoritarian

The Ansari line of thinking does not lead to “civic nationalism” but straight towards subtle minoritarianism.

The Prime Minister did well to indirectly point out this proclivity.

Narendra Modi’s double-edged statement during the farewell to Vice-President Hamid Ansari is perhaps the best way to call out the latter’s inherent hypocrisies. After pointing out that as a constitutional functionary he had to “remain confined” in expressing his personal views, Modi observed that Ansari now won’t have to live with this constraint. “There may have been some struggle within you (all these years) but from now onwards, you won't have to face this dilemma. You will have a feeling of freedom and you will get an opportunity to work, think and talk according to your basic ideology.”

The cheeky side-swipe, reported by The Times of India, is the reference to Ansari’s “basic ideology”, which can be presumed to refer to some form of minoritarian thinking.

Ansari recently spoke his mind on two occasions: one was an address to the National Law School of India in Bengaluru (read the text here) earlier this week (7 August); another came in an exclusive interview to Rajya Sabha TV by Karan Thapar (read the text published in the wire.in) . Both were parting kicks delivered to a government Ansari does not obviously like, but can’t say so openly.

Many of Ansari’s broad points – made not just before his exit, but even earlier – are well-taken. No government should ignore these issues. To point out that Muslims should not have to prove their patriotism day-in-and-day-out is unexceptionable. Nor can anyone take umbrage at his views on the actions of cow vigilante groups, which, given media amplifications, may have spread insecurity among Muslims. And, certainly, his call for better enforcement of the rule of law is hardly controversial.

But the problem is that many of Ansari’s comments seem to espouse minority-centric views, and could even stoke further communalisation of the situation in India.

For example, Ansari, after claiming to stand for civic-nationalism as against religion-based nationalism, suddenly turns around and says that the courts should not interfere with triple talaq.

Here’s what he said when asked by Karan Thapar about his stand on the issue. “Firstly, it is a social aberration, it is not a religious requirement. The religious requirement is crystal clear, emphatic, there are no two views about it, but patriarchy, social customs have all crept into it to create a situation which is highly undesirable.”

Asked specifically if the court should step in, he replied: “You don’t have to; the reform has to come from within the community.”

Where is civic nationalism and the rule of law in all this if the courts are to be kept out of discussing the rights of Muslim women?

Then he talked about religious tolerance, and quoted Swami Vivekananda on it. “We must not only tolerate other religions, but positively embrace them, as truth is the basis of all religions. Moving from tolerance to acceptance is a journey that starts within ourselves, within our own understanding and compassion for people who are different to us and from our recognition and acceptance of the ‘other’ that is the raison d’etre of democracy.”

But this isn’t what is happening all over the Islamic world, where the “other” is being discriminated against, where demands for Sharia rise whenever a Muslim majority government is formed – as we have seen even in Jammu & Kashmir? While it is no one’s case that India should reduce itself to a Hindu version of Islamism, is Swami Vivekananda’s idea of tolerance applicable only to India or even its two Muslim neighbours, both of whom have steadily sent their minorities packing?

Or is tolerance meant to be a one-way street?

There are other contradictions in how Ansari made his points. He says that the “majority” and “minority” are contextual, and asks: “The question then is whether in regard to ‘citizenship’ under our Constitution with its explicit injunctions on rights and duties, any value judgments should emerge from expressions like ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ and the associated adjectives like ‘majoritarian’ and ‘majorityism’ and ‘minoritarian’and ‘minorityism’? Record shows that these have divisive implications and detract from the Preamble’s quest for ‘Fraternity’.”

But at another point he supports “affirmative action” for Muslims, when he could have merely said that anyone identified as socio-economically backward should be entitled to the benefits of affirmative action.

Then he goes around denying that there is any radicalisation among Muslims in India, and if some are joining ISIS, at best it is some individuals going “off track.” If this is true for Muslims, why is it not equally true that “violent gau rakshaks” may also be individuals going “off track?”

One can’t, on the one hand, assert that the actions of a few gau rakshaks have made the entire minority community “insecure” when the actions of a handful of Muslims resorting to terrorism and pouting radical rhetoric may be causing equal insecurities among Hindus. Ansari seems unwilling to acknowledge that there are concerted efforts to Wahhabise Indian Islam, and syncretic practices among Muslims are being sought to be erased by organisations like the Tablighi Jamaat. Practices like worship at dargahs and veneration of pirs are now being labelled as “shirk” – that is, equivalent to the practice of idolatry.

Asked about the situation in Kashmir, Ansari says that “the political immobility in relation to J&K is disconcerting.” He adds: “The problem is and has always been primarily a political problem. And it has to be addressed politically.”

This is, at best, a half-truth. Ultimately, there is no military solution, but when violence has the upper hand, the military must step in and restore law and order. Ansari has also neatly evaded two issues through his formulation that Kashmir is a “political problem”. The ethnic cleansing of nearly half a million Pandits from the valley can hardly be the result of a political problem not being resolved; it also does not take into account the rise of jihadi groups from across the border who believe their job is to Islamise J&K.

This is not the first time Ansari has spoken like a representative of the minorities, rather than for all Indians. Last year, at a convocation of Jammu University, he called on the Supreme Court to figure out how minorities can be protected from majoritarianism and clarify “the contours within which the principles of secularism and composite culture should operate with a view to strengthen their functional modality and remove ambiguities.”

He said in Jammu that “any public discourse on India being a ‘secular’ republic with a ‘composite culture’ cannot overlook India’s heterogeneity…A population of 1.3 billion comprising over 4,635 communities…(and where) religious minorities constitute 19.4 per cent of the total…”

The counter is simple: if we are a country with 4,635 communities, how did several of these communities get aggregated into 19.4 per cent “minorities”, when the logic should lead to the opposite conclusion - that all communities should be seen as minorities with equal rights? Where does majority and minority come in when no community is a monolith? Also, his diatribe against “composite culture” is actually a riposte against the Left and the Congress, which used this term to oppose Jinnah’s Muslim separatist policies.

Clearly, the attempt is to treat Hindus as homogenous when it comes to demanding rights for minorities, but to indirectly deny the same to the majority when it comes to equal treatment even though the “majority” community may exist in thousands of smaller groups.

Ansari’s thoughts do not even pretend to see if Hindus may have been discriminated against, with the state running thousands of temples, but leaving the minorities to manage their churches and mosques without government interference.

The Ansari line of thinking does not lead to “civic nationalism” but straight towards subtle minoritarianism.

The Prime Minister did well to indirectly point out this proclivity.