Vinod Mehta, The CIA mole, And I

The author wishes he could meet the departed journalist who mentioned him, albeit through a typo, in his famous book, to figure out who America’s spy in the Indira Gandhi government was if it wasn’t Morarji Desai or YB Chavan.

The closest I came to meeting the late Vinod Mehta was at a McDonald’s outlet at Connaught Place. A colleague and I walked in to find him munching a burger. “Shall we go and say, ‘Hi’?” My colleague observed him for a while and said it did not appear to him from his withdrawn and pensive look that he would appreciate his privacy getting intruded at that moment. So, the only chance I ever got was gone.

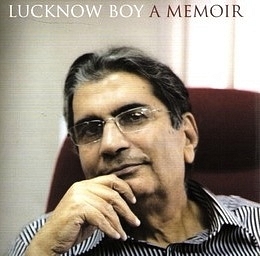

Years later, a typo somewhat spoiled the reference Mehta would make to me in his best known book, the 2010 bestseller Lucknow boy: A memoir. It was with reference to the India’s biggest spy scandal, in which destiny has placed me as a footnote alongside him and a political heavyweight.

The background is quite complex, so a summary would be in order. In the run up to the 1971 India-Pakistan War over what was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), The New York Times first hinted at the presence of a CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) operative within the Indian government. By December, The Washington Post had reported that US President Richard Nixon’s south Asia policy was being guided by “reports from a source close to Mrs Gandhi”.

In subsequent years, as the issue heated up in India, some names were taken. In 1983, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Seymour Hersh alleged in his book Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House that Morarji Desai was the “most important” informer of the CIA, who was paid $ 20,000 yearly by the agency to pass on information during the Indo-Pak war of 1971. Outraged, Desai filed a case in a US court to save his honour. Unfortunately for him, his suit was dismissed on legal technicalities in 1989.

It was a sad chapter in the 87-year-old Gandhian’s remarkable life. The only man who openly came to his defence was his confidant, the inimitable Subramanian Swamy. He called a press conference in Mumbai and said that the “real spy” was a former “deputy prime minister of India and former chief minister of Maharashtra”. When he was asked if he was referring to the late YB Chavan, the Defence Minister in 1971, Dr Swamy gave out his trademark mischievous smile.

Media ignored Swamy’s charge, but they tickled the instincts of a young Vinod Mehta, then an editor with now defunct daily The Independent.

The newspaper’s Delhi bureau was asked check up the facts, and it came back with a copy of an R&AW (Research and Analysis Wing) communication to Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, suggesting that Swamy’s claim was credible. “I mistook the RAW letter as the gospel truth,” rued Mehta in Lucknow boy.

The Independent went on to publish a big story headlined “YB Chavan, not Morarji, spied for the US”. And the furore that followed caused Mehta “much grief and my job”. He even left Mumbai.

I am sure Mehta had forgotten all about this closed chapter of his life, until I reopened it.

In my 2009 book CIA’s Eye on South Asia — a compilation of declassified agency records — I wrote a commentary on the 1971 war on the basis of recently declassified US government records and spotlighted the mole case.

Until this moment, all the charges about the mole, including one peddled by Mehta, lacked any substantiation because there was no confirmation whether or not such an operative ever existed. As such, no constructive discussion on the issue ever took off. I sought to initiate it by giving unassailable evidence in the form of US records, making it clear that the CIA indeed had a “reliable” agent operating out of the Indian cabinet in 1971.

A dramatic turnaround came on 6 December when the mole leaked out India’s “war objectives” to the agency. Prime Minister Gandhi told Union Cabinet that apart from liberating Bangladesh, India intended to take over a strategically important part of the Pakistan occupied Kashmir and go for the total annihilation of Pakistan’s armed forces so that Pakistan “never attempts to challenge India in the future”.

I followed this matter up with two RTI applications with the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) and the Prime Minister’s Office. The outcome made it to the headlines, but they did not lead to any major controversy or constructive discussion.

Unknown to me, and most likely following a favourable review of my book by AG Noorani, Mehta’s interest was rekindled. “There are two important footnotes to this story,” he wrote in Lucknow boy. “As late as 2009, Anju Dhar [sic], author of the book CIA’s Eye on South Asia, wrote to the Central Information Commission via RTI demanding that the government disclose the name of the CIA mole in Indira Gandhi’s cabinet. Anju Dhar [sic] is still waiting for a reply.” It was gratifying to see Mehta make use of some of the dots I had connected in this context.

The second and “historically more significant” footnote according to Mehta was that in 2010 Hersh had personally told him that the mole was indeed Desai, and said that the money was paid to his son Kanti. Mentioning this in his book, Mehta wrote, “I find it hard to believe that Desai would betray his country, and that too for the paltry sum of $20,000 a year.”

I agree. The plain truth is, as was affirmed by a declassified MEA record in 2011, that “Morarji Desai was not even in the Cabinet” at that time. So the very question of his being the mole does not even arise.

My RTI quest, as Mehta noted, remained stuck on account of the government’s refusal to share information.

To elaborate it a little, I put eight questions to the MEA. The most important one sought the names and other details about the people who were in touch with the CIA and leaked details of the proceedings of the Congress Working Committee. This had been claimed by Minister of External Affairs Swaran Singh to his US counterpart William Rogers in 1972 and had made it to a US State Department record, which I got to see after it was declassified.

After initially denying me any information, the MEA — following a direction from the Central Information Commission — accepted that the Indian record of the discussion between Minister Singh and Secretary Rogers was available, but refused to disclose it citing a confidentiality clause. It was, however, claimed that there was no mention of the CIA in it. I don’t think anyone is going to pay much attention to an Indian record when an American one is at hand.

The ministry forwarded the rest of my queries to the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Prime Minister’s Office, both of which said they had no information to share.

My separate application to the PMO was transferred to the Cabinet Secretariat for a response. The questions put related to information and records about Cabinet or Cabinet committees from 3 December 1971 to 7 December 1971 on the subject of the ongoing war, the names of people who attended it and records concerning the claim that there was R&AW communication to Prime Minister Gandhi somehow bringing YB Chavan into the picture.

The Cabinet Secretariat told me that “disclosure of information sought would prejudicially affect sovereignty and integrity of India”.

I took the matter to the Central Information Commission. The then Appellate Authority in the Cabinet Secretariat informed the commission in early 2009 that “after carefully considering grounds of appeal” by me and an “examination of papers places before me, I uphold the decision”.

As my own government stonewalled my requests, I received some further information from America. The Richard Nixon Presidential Library informed me on 14 June 2010 that my request for declassification of certain documents identified by me was approved in part.

Some CIA records declassified as a result of my request by the agency were duly sent to me. They all related to the free flow of information from someone in the Indira Gandhi Cabinet in 1971.

The next year, then Chief Information Commissioner Satyananda Mishra reopened the case and, after a hearing, directed the Cabinet Secretariat “to produce in a sealed envelope the relevant records for our perusal”. Thereafter, he directed the Secretariat to send me a portion from it.

The portion I received contained records, most of which were about the “meeting of the Emergency Committee of the Cabinet held on 10 pm on 3 December 1971” and the meeting of the Council of Ministers held thereafter. My focus was on getting details about the meetings on 6 December — the day according to the CIA record the mole betrayed India’s war objectives — but this was precluded from this disclosure.

At that point, having failed to generate any worthwhile interest in public about the issue, I ended my search for the mole. What I was told off the record by retired top government officials, including from the Intelligence Bureau, was of no consequence unless I had obtained an official confirmation of some sort.

I wish I had the opportunity to share all these details with the late Vinod Mehta.