Warts And All, The Modi Government’s Electoral Funding Reforms Are A Move Forward

The only real criticism of these reforms could be this: clean money does not guarantee clean politics, or clean candidates.

This means we need one more reform: state funding of elections.

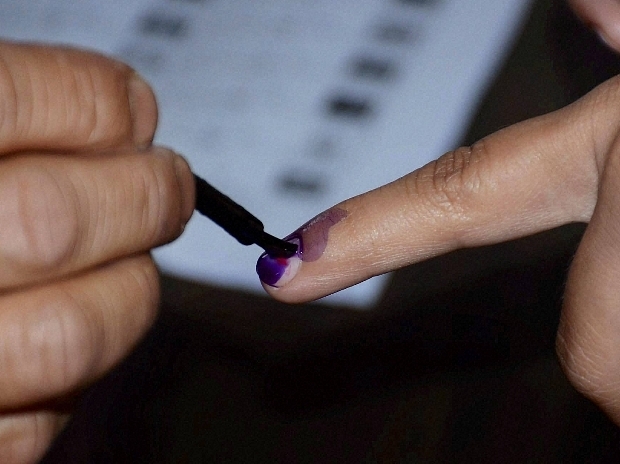

The Finance Bill linked to Budget 2017-18, which the Lok Sabha passed this week, marks a big shift in the journey towards cleaner politics and political funding.

When Narendra Modi demonetised high-value notes last November, one criticism was that the real war on black money should have focused on making political funding transparent. Dirty political money is the Gangothri of black flows. But while the changes proposed in the Finance Bill may not be all that the doctor ordered, it takes a big stab at the problem.

The three changes to clean up political funding are: 1) a ban on cash contributions beyond Rs 2,000; 2) a proposal to issue electoral bonds that can be bought anonymously by cheque by donors and gifted to political parties; and 3) lifting the limit on corporate donations to political parties, but without disclosing which party the money was paid to.

Prima facie, all these ideas can be rubbished. For example, it would still be possible for parties to claim smaller donations in cash; all they need to do is to claim 10 times more smaller donors than before.

Secondly, raising the limits on corporate donations (and the gifting of electoral bonds) while retaining anonymity can hardly be seen as more transparent than the current cash-driven regime. The ordinary voter, for example, would not know if a company paid a political party to get a specific policy changed, thus allowing cronyism and policy influence without fear of being unmasked.

These are valid objections, but it is never a good idea to make the good the enemy of the best. Progress is progress, even if it is not the ultimate in transparency.

It can be no one’s claim that political parties don’t need funding. Why then is it such a bad idea to allow companies to fund them from genuine profits instead of being forced to generate this illegally, which will surely involve even greater policy skulduggery? At the very least, we will know a company paid big money to political parties. It will not be difficult to figure out if it gained unfairly from changes in policies subsequent to the donation. Anonymity does not guarantee absence of critical scrutiny. In any case, even if a company has benefited from favourable policy changes, it does not follow that the policy itself was bad. That needs to be proven on its own merit. Policy changes will thus need greater clarity and must pass the test of not being narrowly focused.

The anonymity point is also overstressed. When donations by companies have to be disclosed, it does not take rocket science to figure out who may have got the money, since parties also have to disclose their accounts at some point. If you are one of India’s major parties, and you know Rs 50 crore was paid by the Tatas and you got none of it, you can surmise where it went. In a charmed circle of politicians, this anonymity will not be easy to protect. Which is another way of saying there will be no real anonymity in the end, especially for large donations. There will only be public deniability.

The only real criticism of these reforms could be this: clean money does not guarantee clean politics, or clean candidates. The same thugs and bandits who enter elections as nominees of political parties will continue to now get clean money for fighting elections through these reforms. It is not difficult to envision jailbird politicians getting white money for their election campaigns.

This means we need one more reform: state funding of elections. It is the lack of resources that ensures that good people don’t enter the electoral arena. And bad people may swipe the clean money. If we can ensure state funding of elections – an average budget of Rs 5 crore per Lok Sabha constituency is not unreasonably expensive for a government which spends Rs 5 crore for every MP under the MPLADS scheme every year – good candidates will emerge.

If bad money and criminalisation of politics drives good candidates out of the arena, good money should embolden some of them to try their luck. We need state funding of elections.

But this quibble apart, the government needs to be complimented for moving the agenda forward on electoral funding reforms.