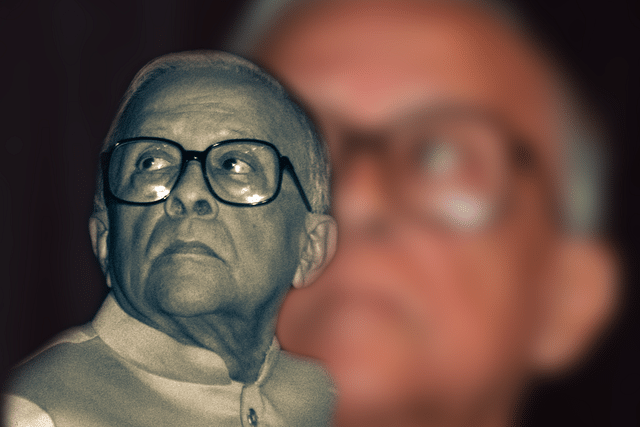

Why Jyoti Basu Does Not Deserve A Memorial

Jyoti Basu, with his poor record as chief minister, does not deserve a memorial, and definitely not something so grand.

Bengal continues to reel under the cumulative effects of his misrule even nearly two decades after he stepped down from power.

A memorial to former West Bengal chief minister Jyoti Basu, who presided over the state for more than 23 years, will come up at Kolkata’s satellite city New Town-Rajarhat. The Mamata Banerjee government has just allotted a sprawling plot of land there to a trust formed by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPI(M) to set up a research centre, which will also serve as a memorial to the Marxist patriarch.

The memorial, which will come up on a prime 5-acre plot that has been awarded to the trust packed with Marxists, will have a museum where articles used by Basu will be displayed. A library for conducting research on Basu and an auditorium will also be a part of the memorial. The proposal for the memorial was mooted by the then Left Front government soon after Basu died in January 2010. What’s more, the land for the memorial has been given away at a throwaway price.

The Initial Proposal

The initial proposal was to convert Indira Bhawan, a two-storey bungalow in Kolkata’s Salt Lake area where Basu used to live, into a museum dedicated to him. The Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee government considered the proposal, but somehow it did not materialise. Indira Bhawan was originally built by the then Congress government of the state to house Indira Gandhi during the 74th All India Congress Committee (AICC) session in December 1972. It then became the state guest house, where visiting dignitaries used to stay.

Basu moved into this upscale bungalow in August 1989 (when he was the chief minister) and made it his official residence. Before that, he used to reside in his ancestral house in south Kolkata. He was allowed by his successor — Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee —to retain the bungalow even after he stepped down from office in November 2000 on the grounds that he (Basu) had Z+ security cover.

Basu continued to enjoy state hospitality — a battery of caretakers, housekeepers, gardeners, cooks and other staff deputed by the state government — until his death. A large contingent of state police was also deployed at and around the bungalow. Half the carriageways running beside the boundaries of the bungalow were cordoned off with barricades to keep away motorists and pedestrians, and this caused many accidents and daily traffic snarls.

Incidentally, after Banerjee swept to power in 2011, she decided to house an academy dedicated to Kazi Nazrul Islam in the bungalow. This sparked immediate protests from both the CPI(M) and the Congress. Both the parties wanted the legacies of their respective icons — Basu and Indira Gandhi — associated with the bungalow to be preserved.

The row even strained Banerjee’s ties with the Congress central leadership when she was a part of the United Progressive Alliance-II government. Ultimately, and in view of the political row that erupted, Banerjee scrapped her decision and shifted the proposed Nazrul academy to a new building.

After the CPI(M)’s proposal to convert Indira Bhawan into a museum dedicated to Basu did not fructify, it hurriedly formed a trust, and a 5-acre plot of land in New Town-Rajarhat’s central business district was allotted to the trust by the Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee government in 2010.

The trust paid Rs 5 crore, a small fraction of the commercial price of the land, for the 5-acre plot allotted to it. But with power changing hands in 2011, the proposal was relegated to cold storage. It was only in end-June, after a CPI(M) delegation met Banerjee, that the state government approved the allotment of the plot to set up the proposed ‘Jyoti Basu Centre for Social Studies and Research’.

But this has revived the controversy over building memorials to communist leaders. Communist theory disapproves of deification, or promoting personality cults, of any communist. Such deification is termed as ‘bourgeois’ and ‘counter-revolutionary’ in communist parlance. That, however, has not stopped communists from all over the world from erecting memorials and deifying their so-called ‘leaders’ like Mao Zedong, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin and Fidel Castro, who stand accused of mass murders and human rights violations.

But apart from the proposal of establishing a memorial and a museum to Basu, what also rankles is the issue of the throwaway price at which such a land has been given to the CPI(M) trust.

According to conservative estimates, the price of one katha of land in the central business district of New Town-Rajarhat is nothing less than Rs 30 lakh. And 60 kathas make an acre. Thus, the cost of one acre of land in that area would be Rs 1,800 lakh, or Rs 18 crore, and the 5-acre plot would cost a minimum of Rs 90 crore. Instead, the CPI(M) trust has got away by paying a miniscule 5.5 per cent of the commercial value of the land.

The satellite city of New Town-Rajarhat is being established on land that has been acquired from thousands of farmers and landowners after paying them compensation. The land has then been developed by the state government and vital infrastructure like roads, flyovers, drains, sewers, street lights, water supply lines and other civic amenities constructed with funds from the public exchequer before the land was plotted, and commercial sale began. Acquisition of this land at such a ridiculously low price causes a huge loss to the state exchequer.

Basu’s Dark Legacy

But much more than ideology and ethics is the issue over the need to have a memorial dedicated to Jyoti Basu. Basu, by all accounts, oversaw the sharp decline of Bengal. It was under his watch — he was the chief minister of Bengal from June 1977 to November 2000 — that Bengal’s slide into poverty and backwardness gained momentum. The ‘militant’ trade unionism that he and his party encouraged resulted in the closure of thousands of industrial units and the conversion of Bengal into an industrial graveyard. That led to large-scale unemployment and the state’s economy hitting its nadir.

The education policies Basu initiated contributed to the decline of some of the finest education institutions in the state. Under Basu, the politicisation of education resulted in the rise of mediocrity and the flight of intellectual capital from the state. Politicisation of the bureaucracy and injection of trade unionism into the state workforce, and even the police constabulary inflicted permanent damage to Bengal’s work-culture and to its public institutions.

Another black spot in Basu tenure is, inarguably, the Marichjhapi massacre in which thousands of poor Bengali Hindu refugees, almost all of them Dalits, from East Pakistan were brutally murdered by police and CPI(M) cadres. The massacre was successfully covered up that time by Basu and his government.

Other similar incidents include the infamous Bantala rapes where three women — two of them senior officers of the state health department and another a UNICEF official — were brutally raped and one of them murdered by CPI(M) cadres. They had reportedly unearthed a racket involving large-scale embezzlement of UNICEF funds by CPI(M)-controlled rural bodies. Basu, infamously, dismissed the brutal rapes and murders with a “these small incidents happen at times” remark.

Another incident during Basu’s tenure, and he was dismissive of this as well, was the Bijon Setu massacre of 18 monks and nuns belonging to the Ananda Marg order in the heart of south Kolkata in broad daylight. The monks and nuns, on their way to attend a conference at their headquarters, were pulled out of vehicles, hacked to death and then set afire by Marxist cadres (read this). The CPI(M) was allegedly eyeing the prime land on which the order had built its headquarters. Hundreds of political rivals were murdered and their bodies disposed of by CPI(M) functionaries during Basu’s tenure.

Bengal, under Basu, became a poor and backward state where the police and the state machinery became adjuncts of the CPI(M).

Basu, with his poor record as chief minister, does not deserve a memorial, and not definitely something so grand. Bengal continues to reel under the cumulative effects of his misrule even nearly two decades after he stepped down from power.

What should, instead, be constructed is a memorial to the tens of thousands killed during his time as chief minister. It should have detailed accounts of his misgovernance and serve as a permanent reminder of what the communists are capable of.