Worshippers Of Annabrahma: Dalit Movements In Bengal During The British Raj

A record of the Dalit movements in colonial Bengal and why they were too complex to be boxed into simplistic categories

The Dalit movement in Bengal emerged during the British period under the gale of colonial modernity, which at one end threw open endless possibilities for the subalterns and on the other, made the realisation of those possibilities a distant dream. In fact, the arrival of colonial rule was a rupture which pulled Indian society in various directions. It is not surprising that Dalit movements emerged in all points of contacts with colonialism, be it Bengal, Madras or the Bombay Presidency.

In Bengal, the institution of the zamindari system strengthened the upper-castes’ stranglehold over the society by causing mass dispossession of land by extinguishing the traditional rights over it. But one the other hand, the same colonial rule offered the subalterns nominal equality under the eyes of law and state for the first time and one could find the anomaly of a rich peasant among Dalits. But the interaction of the market economy was limited to the landlords and rich peasantry only and did little to disrupt the traditional agrarian relation, unlike what was seen in present day western Uttar Pradesh. In this region, the growth of capitalist mode of relations in agriculture replaced the traditional labour with wage-labour, a most significant shift which led to far reaching changes in social relations in the region and laid the foundations of the strong and persistent Dalit assertion in the territory.

The pre-20th century Dalit movements primarily took the form of socio-religious assertions, which sought to create a public sphere separate from the Savarna Hindu’s religious structures. One such movement was the Kartabhaj movement, which emerged in the late 18th century. The Kartabhaj movement carried forward the legacy of the Tantric Buddhist sects, which once upon a time were prominent in the region. The term karta was used in the Hevajra Tantra, which means prime mover and scholars claim that it was transformed under the influence of the Chaitanya movement and later under the capitalist modernity to mean infinite master/lord himself. It also had links with the Sahijiya movement of Bengal. It drew people from all castes and creeds and propagated a vision which was resolutely anti-caste. They rejected the Vedas and all rituals and instead focused their faith on love and devotion. A song of the Kartabhaj is indicative of their worldview:

There is no division between human beings;

so why, brother, is there sorrow in this land?

In their Sahaja own Self nature,

Does the infinite take form in every land.

In one way, it can also be seen as the last vestige of the mediaeval Bhakti movement but on the other hand, the language deployed by it was draped in modern imagery. They proclaimed a ‘new secret market place’ different from the ‘old market place’ of Chaitanya which had been corrupted by caste discrimination and other ills. This new market place was open to all of the ‘gorib company’, the company of the poor, and had no king, no master. There was no punishment, no fear. The punishment of theft was the grant of infinite wealth by the company! The celebration of ecstasy and eroticism and breaking of social norms was perhaps the legacy of the old tantra traditions, although Kartabhaj wasn’t a tantra tradition in itself. It was an imagination of a utopian future of abundance informed by the new capitalistic modernity now visible on the horizons, ‘a secret marketplace’ where those suffering under the feudal caste order could escape.

Later, with the development of the modern polity and political consciousness, the Dalit movements took the form of political mobilisation on the issues related to economy and representation. Two communities - Namasudras and Rajbansis led this new Dalit assertion in Bengal.

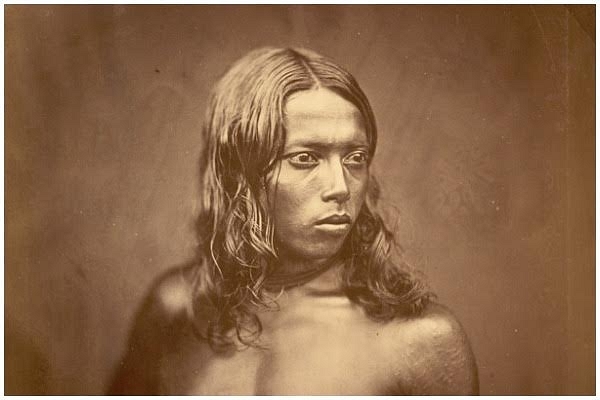

The Namasudras, earlier known as Chandals, lived in the eastern districts of Bakarganj, Faridpur, Dacca, Mymehsingh, Jessore and Khulna while the Rajbansis, earlier known as Kochs, were heavily concentrated in the districts of Rangpur, Dinajpur Jalpaiguri and the state of Cooch Behar. The geographical concentration of both the communities points to the possible tribal origins of both.

The majority of Namasudras were either rent-paying cultivators or agrarian labourers although the colonial rule had induced some economic mobility and some of them took to various professions as well. This also led to aspirations for the higher social status and wider acceptance. In 1873, Choron Sapah from the community decided to throw a feast and invited members of all castes of his village in the Faridpur district. The mere invitation infuriated the upper-castes of the region who threw taunts at the Namasudra women saying how could they share meal with men who are employed in lowly works and whose women roam around the marketplace? This sparked a major protest followed by strike by the Namasudras, which took the form of complete social and economic boycott of higher castes in the Faridpur-Bakarganj region. It also led to the Namasudras forming various committees and organisations aimed at educational and social advancement of the community especially after the The All-Bengal Namasudra Conference was held at Dattadanga in Khulna district in 1881.

The stiff resistance by the higher castes to the opening of schools for the Namasudras led them to turn towards the British officials for assistance. In 1908, an English-medium high school was established in the Orakandi village of Faridpur. The entrenched caste discrimination and denial of accommodation to the Dalit students in Kolkata finally led to University of Kolkata renting out a separate building in the city in 1917. The Proportional Representation of Communities in Public Employment Act gave the much needed avenue of socio-economic mobility to the Namasudra.

The social movement also led to development of a new religious reform movement - the Matua Mahasangh under the leadership of Harichand Thakur. The Matua movement totally rejected the caste and varna system and even the Guru parampara of the Bhakti movement. It instead emphasised on the ecstatic kirtans and glory of the ‘name of lord’. The kirtans themselves became the songs of protests and self-respect. An example from ‘Caste, Protest and Identity in Colonial India: The Namasudras of Bengal’ by Sekhar Bandyopadhyay is as follows:

The devotees of Matua, with bare chests and unbridled hair,

Stand and say victory to Harichand.

Beat your drums, get rid of all your fears

And hoist your flag up into the sky.

What are you thinking of,

do you want to behave live dead while you are still alive?

Though you are great, you have been denied honour.

So awake, O Brave men.

Hold your heads high, do not give up self-respect,

even though you have to sacrifice your life.

Unlike the Vedantic religious movements creating ripples in the Bhadralok, Matua movement celebrated materialism. For Harichand, Vedanta and its message of renunciation of world was an ideology of despair and prevented people from resisting their subordinate conditions. For the Matua Mahasangh, worshiping goddess of wealth was more logical. It argued for the worship of Annabrahma rather than Parbrahma because for the hungry, food was god. Here, we already see the divergent path from the Savarna socio-religious movements being charted by the Dalits in Bengal, which would ultimately also manifest themselves in divergent political paths.

Similarly, several social movements began among the Rajbansis demanding higher social status. In 1891, the Rangpur Bratya Kshatriya Jatir Unnati Bidhayani Sabha was established. Due to relatively better conditions of the Rajbansis, these movements were mostly under the leadership of zamindars among them like Mahriram Chaudhuri, Rai Sahib Panchanan Barman, Haramohan Khajanchi. They were more focused on claiming higher social status and at the same pleading for government intervention for the upliftment of the economic and educational conditions of the community and recruitment in the government jobs, including the army. With the beginning of the elections to the public offices, political representation became a central point of the Dalit politics. But despite some political representation, mostly at the local level, the share in the political power eluded Dalits, causing a growing distrust towards the Congress-led nationalist movement. For Dalits, nationalist movement largely remained a movement of Savarna Bhadraloks and the gulf was never bridged, despite attempts by various luminaries from the either side of the divide. The coercion used by the higher-caste Hindus to include Dalits in the Swadeshi movement created a revulsion which persisted in all subsequent movements like Non-Cooperation and Civil Disobedience.

In their ideological worldview, Dalits were conflicted between supporting the British rule, under which old disabilities has lessened and opposing the British rule which upheld the Zamindari system and hence, daily caste oppression by decisively intervening in the favour of the mostly upper-caste Zamindars in the case any conflict. There are many instance of Dalits taking up arms against the colonial state machinery but they all remained outside the ambit of the larger nationalist movement. Similarly, the relations with the Muslims also remained complicated. Sometimes there was common cause to be made with the Muslim peasantry especially after the emergence of the class-based Praja movement. At other times, there were pitched battles fought with the Muslims like in 1911, 1923-25, 1938. In fact, ‘Dangdhari Mao’ or the club wielding mother of the Rajbansis became a movement in itself against the Muslims over the issue of kidnapping and dishonour of Dalit women.

Overall, the Dalits of Bengal found themselves sandwiched between hostile Muslims and Savarna Hindus who dominated the public sphere and continued to deny them political space and mobility. Although, after the Poona Pact, which compelled Gandhi and the Congress to finally do something about the caste issue, there was some accommodation of Dalits in the nationalist movement. In the 1937 elections, the class politics of the Krishak Praja Party collapsed under the weight of the Muslim communalism and frequent anti-Hindu riots became a regular occurrence with the support of the government. Dalits were the prime victims of increasing Muslim aggression, which also led many to shift towards the Hindu Mahasabha due to their distrust of Congress and also due to the general Congress policy of surrendering to the Islamic belligerence. But, as the larger apathy and distrust between Dalits and Savarna Hindus had permanently weakened the nationalist movement in Bengal, Dalit politics pulled in different directions even as India hurtled towards Independence and Partition. The story of historical blunder of Jogendra Nath Mandal of supporting Pakistan and leading the Dalits of east Bengal towards the largest genocide after the Second World War is too well known to be repeated.