India needs her Swatantra

Book Review: Gurcharan Das, India Grows at Night: A Liberal Case for a Strong State (2012)

One of the distinguishing features of modern India is the dichotomy between private success and public failure. This is especially, though by no means exclusively, evident in the economic sphere. Private businesses tend to be run efficiently, providing quality goods and services comparable with the best in the world. From airlines to automobiles; from consumer goods to information technology, examples of well-run companies and satisfied customers abound. Government services, on the other hand, are more or less a shambles. They are poorly managed and badly run, providing sundry apparatchiks with ample opportunities for self-aggrandizement.

The quality of services provided is often appalling. Witness the proliferation of fee-charging private schools across the length and breadth of the country. Despite being free, no parent who can afford it would even consider sending their child to a government school. The same is true for hospitals, the public distribution system and nearly every other area where the state is active. All stories of interactions of the citizen with the state- in matters as diverse as life, death and taxes- are invariably a mix disappointments and frustrations.

The same dichotomy is evident in the socio-cultural sphere. Indians who go to great lengths to keep themselves and their homes clean seem to be strangely oblivious to any notion of public hygiene. People who may be scrupulously moral in their personal lives think nothing of bribing the government to get favours or looting the exchequer with impunity.

Gurcharan Das, an acclaimed, avuncular public intellectual, tries to make sense of this dichotomy. In his celebrated work India Unbound, Das had chronicled the economic rise of India. The credit for this, he argued, was private enterprise, whose latent energy was unleashed following economic liberalisation in 1991. In India Grows at Night, he looks at the other side of the equation: the continuing failure of the state. India, he contends, has grown despite the state. But it could grow at a much faster pace and in a more equitable and orderly fashion if the state gets its act together. A lethargic, incompetent state is holding India back.

Das provides classical liberal prescriptions for dealing with India’s governance crisis. He calls for a strengthening of the rule of law, institutional accountability and respect for individual and property rights. This, he says, can only be achieved if India has a ‘strong’ state. All of this is unexceptionable. The book is a bit fuzzy on how we can get there. He believes that a change is possible if we return to the Indic notion of sadharana dharma, which can be loosely defined as doing the right thing. Das views the middle class awakening following the corruption scandals and the Anna Hazare movement as a precursor to a return to this Gandhian idea.

This seems to be a bit idealistic. Call me a cynic, but the reality is that there has never been a shortage of people willing to pay lip service to these high-minded ideals. A flick through any of the myriad 24×7 news channels would be enough to confirm this. What is required is a proper alignment of incentives that would mold the behaviour of people in desirable ways.

The solution for a country like India is on focusing and strengthening the areas that are the state’s core competence: external and internal security; quick and efficient dispute resolution; and a transparent and unbiased regulatory set-up that acts as a check against both bureaucratic red tape and crony capitalism. The trouble is that instead of a single-minded focus on getting this right, a dirigiste state has digressed and spread its attention and resources on doing everything from distributing wasteful entitlements to running banks and airlines.

In other areas where state intervention is required- notably in rebuilding the country’s creaking physical and social infrastructure- the way forward is through public-private partnerships, where private ownership is complemented by public oversight. This has already been done with considerable success in areas such as construction of highways. It needs to be extended to other sectors, including education and healthcare. There is no reason why the government should continue to run a sprawling network of ramshackle schools and hospitals when the data consistently shows that citizens prefer their privately run counterparts.

The solution is to divert resources from running schools and hospitals to providing cash vouchers directly to the poor, allowing them to use these to access good quality education and healthcare. If the poor are then unhappy with the quality of services, they would have the option to take their cash vouchers elsewhere. Competition breeds competence. Bad schools and hospitals with incompetent teachers and doctors would lose out, and good ones rewarded, improving overall outcomes. Das clearly approves of such ideas, but in this slightly muddled book, they are not enunciated with the clarity they deserve.

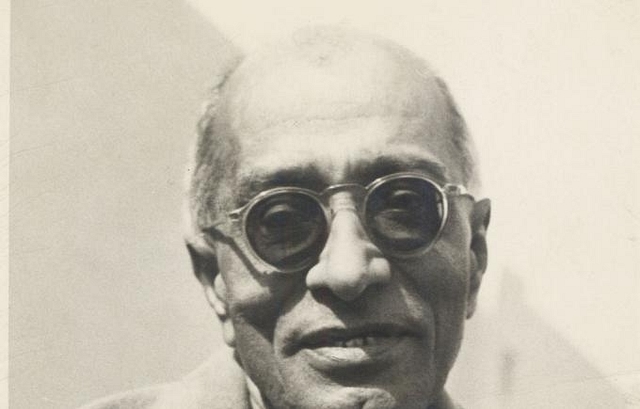

If his treatment of the exact role of the “small but strong” state is slightly underwhelming, he makes up for it by throwing his weight behind an intriguing idea that deserves more attention. Disappointed with the existing political options in the country, Das calls for a revival of the extinct, classical liberal Swatantra Party. Not many people are aware today that Swatantra- “freedom” in Sanskrit- was the largest opposition party in the country in the 1960s. It was blessed with a set of talented leaders and led by the formidable polymath and freedom fighter, C. Rajagopalachari.

It fought against the existing Nehruvian consensus at a time when socialism was still in vogue. Its passionate advocacy of libertarian ideals made the public discourse far more interesting. Sadly, it was a party ahead of its time- India was much poorer and socialism was still not discredited at the time. It was swept away by the competitive populism of Indira Gandhi and Jai Prakash Narayan in the 1970s.

India is a different country today: more prosperous, urban and aspirational than at any time in its independent history. And yet, the available political choices are the ones forged in the rough and tumble politics of the 1970s and 80s. At the state level, we have an agglomeration of leftist, casteist and regional parties, many of them family run, which are committed to distributing more entitlements and resources to favoured groups. At the national level, the ruling Congress Party is controlled by the Nehru-Gandhi family and dedicated to massive welfarist schemes and to distributing governmental largesse to targeted groups.

The opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is tethered to Hindu reactionary organisations, whose politics is based on socially illiberal ideas of Hindu revivalism. It’s commitment to economic liberalism is ambivalent at best, as it opportunistically opposes economic reforms while out of power and blindly supports expensive welfare measures for fear of being branded ‘anti-poor’. Irrespective of your political affiliations, it would be fair to say that there was a genuine philosophical debate to be had on the merits of the recently passed Food Security Act and the Land Acquisition Act. Depressingly, there was unanimity amongst our lawmakers cutting across party lines on the efficacy of these measures.

It is this ideological gap that the Swatantra Party would fill. At the political level, it would give credence to the liberal-constitutional idea of the individual as the primary unit on the basis of which the state deals with its citizens. This would be a refreshing change from the competitive group-based identity politics practiced by practically all political parties today. At the economic level, it would be a robust voice in favour of economic reforms and free enterprise, opposed to both wasteful entitlements and the cosy nexus between politicians and big business that is, in fact, antithetical to genuinely free markets.

Demographics are on the side of such a change. As the urban middle class continues to grow, it creates a ready constituency for such ideas. The time is ripe for a modest beginning- perhaps in the form of a Swatantra Club- that could advocate classical liberal ideas in the public sphere. It can also act as a pressure group that could influence lawmakers in at least 50-60 urban parliamentary constituencies in the country.

Das’ principal argument in this book: the need for a small but strong state is both timely and important. But he deviates into philosophy, religion and popular anecdotes too often and fails to adequately flesh out the contours of such a state. That is the principal shortcoming of this book, which otherwise has its heart in the right place. This deficiency is overcome when the book turns to political pamphleteering, as Das throws his intellectual heft behind the idea of reviving a classical liberal party. A distinct libertarian voice would play an important role in arguing for limited government and individual liberty, allowing each Indian to choose her own path in her pursuit of happiness.

[Parag Sayta is a London-based corporate lawyer. The views expressed are personal].

Image Courtesy- Caravan via Google Images