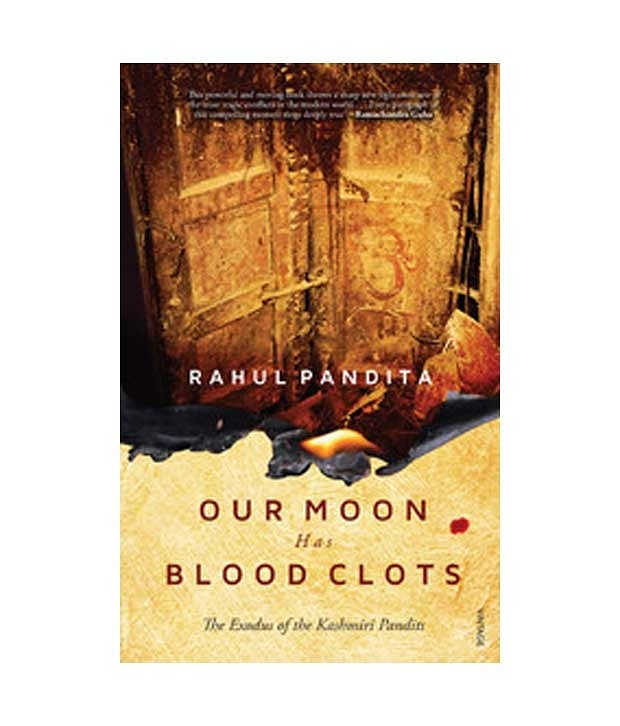

“Our Moon Has Blood Clots” - Review

Rahul Pandita’s “Our Moon has Blood Clots” is an eye opener in many ways. The first generation of victims’ fear of facing the past, the next generation’s apathy, the rhetoric of the political class and the propaganda of anti-national forces have all pushed the tragic story of the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits into near-obscurity. The book pierces through this haze of controversies to show the magnitude and character of violence that was unleashed against the Pandits. Pandita takes head on all attempts to belittle their suffering. Be it suggestions of Jagmohan’s hand in the exodus or propaganda about the safety of Pandits who chose to stay back, Pandita shatters many such myths with first-hand evidence and cogent logic. The book stands out for its detail and from Pandita’s words it appears that this feat was a direct result of his own trauma- “Like the tramp in Naipaul’s In a Free State, I have reduced my life to names and numbers. I have memorized the name of every Pandit killed during those dark says, and the circumstances in which he or she was killed.”

What Pandita is very clear about is his conviction regarding who is guilty. He criticizes the media’s obsession with the Indian state’s brutalities on Kashmiris for failing to see “the fact that the same people also victimized another people.” By drawing attention to facts like the hostile utterings of the household’s milkman and change in behaviour of a close friend, Pandita makes a forceful point regarding the role of the average Kashmiri Muslim in the exodus. As Vinod Dhar, the only surviving member of his family testifies to Pandita “when the gun shots were being fired, the people of the village increased the volume of the loudspeaker in the mosque to muffle the sound of the gunfire.”

Historically the Pandits have been subjected to humongous cruelties, but only by foreign rulers and invaders. As Pandita describes, older victims of the exodus like his uncle recollect the terror unleashed on Pandits in 1947 with a lot of trauma. But that was the handiwork of Pathan raiders of Pakistan. It is well known that Kashmiri Muslims were so integrated with Kashmir’s unique cultural fabric- Kashmiriyat– that Jehangir found it “hard to tell a Kashmiri Hindu apart from a Kashmiri Muslim”. Islam in Kashmir did not wipe out local customs and identities the way it did in many parts of the world. So, why did such a people turn so blood thirsty in the last few decades? If it was only the Indian state’s ‘oppression’ through manipulation of elections or even economic deprivation that led to demands for “Azadi”, why did there have to be so much hatred against a minority community? This is exactly what Pandita asks-“I can’t fathom why all this is happening. If the Kashmiris are demanding Azadi, why do the Pandits have to be killed?…How is the burning of a temple or molesting a Pandit lady on the road going to help in the cause of Azadi?” In answering these questions lies the only way of finding a real solution to India’s Kashmir problem; in realising that all traditionally offered justifications for “Azadi” are at best superficial.

In his memoirs, Jagmohan identifies the state’s “soft and permissive attitude” and the consequent rise in fundamentalist Islam as major “roots” for the chaos that engulfed Kashmir. There was a sharp rise in the popularity of Islamic thought of the Jam’ati-I-Islami variety during the few decades preceding militancy in Kashmir. Parties in power were not only permitting but also competing with organisations like the Jama’at to promote pan-Islamist ideas, for maintaining the electoral edge. This strain of Islamic thought was fundamentally opposed to any local Muslim culture or nationalism and formed the basis for future attempts to establish what Prof. Riyaz Punjabi calls a “new Islamic state to stretch from Kashmir through Pakistan to Afghanistan, Iran and Central Asia…Caliphate of the medieval times.”

Pandita’s book gives a clear glimpse of where this change in Kashmir’s religious and cultural fabric led its people to by the 1980s. Children were playing Cricket in school with the team captained by a Muslim student calling itself Pakistan and the one captained by a Pandit boy calling itself India. Crowds celebrated on streets when the Indian Prime Minister was assassinated. They celebrated “Diwali” when Pakistan won the Austral-Asia cup in Sharjah in 1986. In the valley where “the biggest crime” that was heard of “was how in a fight sometimes a man would pull out his Kangri from underneath his pheran and hurl it at its opponent”, the Pandits were being made the target of terrible violence and riots on flimsy pretexts. With the advent of militancy all pretences of Kashmiri identity were thrown to the wind. Ultimatums were issued to Muslim women to follow “Islamic standards”. Sufi shrines were destroyed. The loudspeakers of Mosques, apart from being used to raise war cries against Pandits, played music eulogizing the struggle of Mujahideens all over the world. Pandita diagnoses the pan-Islamic roots of “the earthquake…that toppled everything in Kashmir”- “It was only much later that we were able to connect this turmoil to the world events occurring around the same time. The Russians had withdrawn from Afghanistan nine years after they swept into the country. In Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini had urged Muslims to kill the author of The Satanic Verses. In Israel, a Palestinian bomber struck in a bus for the first time, killing sixteen civilians. A revolution was surging across Eastern Europe; and a bloodied frenzy was about to be unleashed against the Armenian Christian Community in Azerbaijan.” The Kashmiri Muslim was losing his “Kashmiriyat” for a pan-Islamic identity.

Through this book Pandita has not only brought to light the unspeakable suffering of his own family and the Pandit community in general but has also succeeded in putting his memory “in the way of the untrue history” that was being written about Kashmir and its tragedy.

It is clear from Pandita’s description of the attitude of his compatriots that the Pandits have little hope of returning “home”. This is understandable partly because we fellow-Indians and our Governments have not offered the Pandits anything that can be of hope. But is there also something in the attitude of the Pandits that has contributed to the present situation? Pandita narrates how his father banned him from attending a RSS Shakha in Jammu saying “we are not here to fight but to make sure that you go to school and get your education.” He justifies his decision to follow his father’s advice by referring to the murder of Ehsan Jaffri in Gujarat much later, as if the RSS was responsible for it. The roots of this attitude, however, can be found in the story that Pandita says formed the “thumb rule” of Pandit lives- “Two boys got into a verbal duel…it turned into a fistfight…The fact that his opponent was a Pandit gave the other boy strength. Nobody was expected to lose to a Kashmiri Pandit in a physical fight.” The decision of Pandita, or for that matter many Pandits of his generation who have gained fame and affluence through determination and toil, to turn away from organised activity like the RSS appears to be borne not out of ‘humanity’ as Pandita would like us to believe but out of what Savarkar calls the “docility and mildness of the Hindu.”