Chipmaking Giant Nvidia ‘Arms’ Itself For An AI-Driven Future

The acquisition of the quintessentially British tech player ARM by US graphics processor leader Nvidia will create a global silicon chip behemoth.

How will this impact thousands of India-based engineers, whose innovations fuel both companies?

The ballroom of the Leela Palace Hotel in Bengaluru took on an unusual avatar one day in November 2005: it was transformed, albeit for just a few hours into the boardroom of the iconic Cambridge (UK)-based chip design company ARM (originally Acorn RISC Machines).

For the first time in its history, the company was holding its annual meeting of the board of directors outside Britain.

“I want our directors to get a feel for how much of the innovation that goes into ARM cores flows from India,” Sir Robin Saxby, ARM’s co-founder and chairman told me. At that time, ARM had an ecosystem of over 5,000 India-based engineers with dedicated research and development (R&D) centres based in the premises of four Indian partners: Wipro, Mindtree, HCL and Sasken.

Coincidentally, nine months before, that same year, another international tech player — the US Silicon Valley-based Nvidia — set up its own R&D centre in Bengaluru with an initial team of 50 Indian engineers.

In the 15 years since, both companies have seen their India-based engineers grow in numbers, while contributing crucial intellectual property (IP) to their respective product lines.

Key software that fuelled Nvidia’s flagship GeForce single-chip graphical processors was written in India.

ARM never developed chips; rather it developed the core software and architecture for a generation of system-on-chip (SoC) solutions that run most of the world’s mobile phones starting with the pioneer among them, the Nokia 6110 handset. India-based engineers contributed large chunks of this software.

There was not much in common with the end products of these two families of India-based innovators: ARM was to be found under the hood of Lilliputian devices, cell phones and thousands of smart devices clubbed under the name, Internet of Things (IoT) such as car-controllers, air-conditioners, washing machines, video door bells etc.

Nvidia’s forte was graphical computing — handling huge video and audio files — and increasingly the company’s products found their way into massive supercomputers and servers; some of their devices were large as a paperback book.

Early on 14 September, India time, the two companies made simultaneous announcements in Santa Clara, California (US) and Cambridge (UK) that Nvidia was to acquire ARM for $40 billion from Japan-based investment bank, SoftBank, which had acquired control of ARM in July 2016 for $32 billion. Nice going for SoftBank, which has made a nice chunk of change by its buy-and-sell act in just four years.

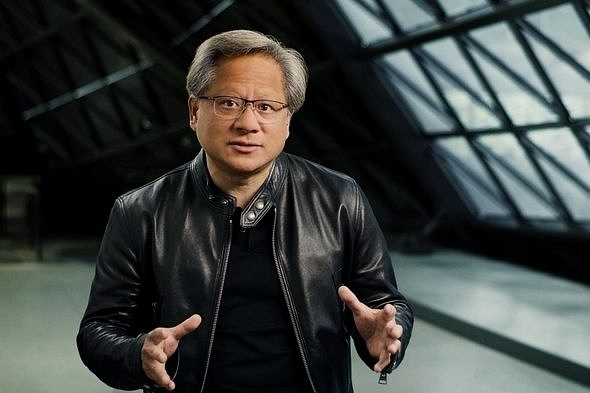

At a global media conference call on Monday (14 September), Nvidia co-founder and chief executive officer Jensen Huang and ARM CEO Simon Segers, whom Sir Robin had hired during the company’s formative years, stressed that the British DNA of the latter would remain untouched, and that it would continue to be led from Cambridge. Indeed, Jensen added that Nvidia would be setting up a new global centre of excellence in artificial intelligence (AI) and would invest in an ARM-powered supercomputer, both at Cambridge.

An ARM Supercomputer

That ARM, hitherto associated in the public mind with thumb-nail-sized chips in phones could, in fact, in sufficient numbers, fuel a supercomputer became apparent in July this year, when the bi-annual Top500 rankings of the world’s supercomputers were announced.

The world’s fastest computer, ‘Fugaku’, based in Japan, was the first ever to be powered entirely by ARM processors from Fujitsu.

The number two-ranked supercomputer, the ‘Summit’, by IBM, ran on the company’s Power processors — and on dozens of Nvidia’s Tesla graphical processors.

This development underlines what a processing behemoth the acquisition has created — a single entity now offering processors for the biggest and the smallest computing applications.

It also suggests what India watchers are suggesting — that in the short term it will be business as usual at the R&D centres of Nvidia and ARM as their portfolios have no overlap.

A Graphics — General-Computing Sangam

But in the future? Jensen Huang is not just Nvidia’s CEO since the company’s founding in 1993. He is a shrewd engineer, who has been slowly, but relentlessly pushing his flagship line of graphics processing units (GPUs) into the mainstream of general processing which uses what are known as central processing units or CPUs. The unsaid mantra is: “If my GPU can do it all, why do you need a separate CPU?”

So successful has his onslaught been that a new acronym has emerged: GP-GPU or general purpose graphical processing unit, sangam of graphics with general computing.

The moral: one processor family, if not one size, fits all. And with Intel, the other chip giant, announcing in July that it would no longer manufacture the processors it designed as its fabrication technology was lagging current technology, Nvidia's position is further strengthened.

As we do more and more movie watching, uploading on YouTube or creating TikTok-type short videos on our phones, the little processors from ARM and the graphical solutions from Nvidia will morph into a single slab of silicon — one day.

It will encash the explosion of AI that everyone expects. When that happens, the India-based innovators of Nvidia and ARM may find common ground and a single goal. But don’t rush, it isn’t happening just yet.

The China Syndrome

Even as India and the world woke up to the Nvidia-Arm announcement, one piquant possibility was being aired by experts. What happens to ARM’s hitherto neutral positioning as a company that would license its IP to anyone who paid, no questions asked.

It is estimated that Chinese phone makers alone pay ARM millions of dollars annually as royalty. This was fine because the UK government too had no issues with where ARM made its millions.

But when ARM becomes an American entity, would it be subject to the Donald Trump-inspired ‘be nasty to the Chinese’ policy that seems to drive official US trade policy? Like India, when it comes to Chinese apps, the US has been aggressive with its corporations in demanding that they cut off links with China —Huawei is a prime example.

Thousands of companies embed ARM IP in devices and solutions that they make and sell in China. Are they threatened now? ARM has a subsidiary based in China. What is its future?

Jensen is of Taiwanese extraction but he is also something of an icon for young Chinese professionals. I attended Nvidia’s first developer ‘mela’ some years ago in San Jose, California, and was bunched with the Chinese media for our interview session with Jensen. They didn’t ask any questions that I found serious. All they were interested in were keepsake photos with the great man.

Predictions are that he will work out a deal with China that will see earthy business sense overcome politics — in all markets. And it remains to be seen how the China policy of the US plays out after the 3 November presidential elections, which may or may not see Trump back at the White House.

The betting is ARM's financially savvy 'neutrality' will survive the merger — and any Sino-American hiccups.