Explained: How Pakistan Plans To Move ICJ Over Kashmir Issue And The Many Hurdles It May Face

If Pakistan moves ICJ over Kashmir, its case is likely to be shot down.

It is bound to fail. Here’s why.

A month after it was humiliated on the world stage with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) voting 15-1 in favour of India in the Kulbhushan Jadhav case, Pakistan has announced that it will approach the court on the Kashmir issue.

Pakistan’s move comes amid its failure to ‘internationalise’ the Kashmir issue following India’s revocation of Article 370 of the Constitution, which gave Jammu and Kashmir a host of ‘special rights’ labelled temporary and transitional.

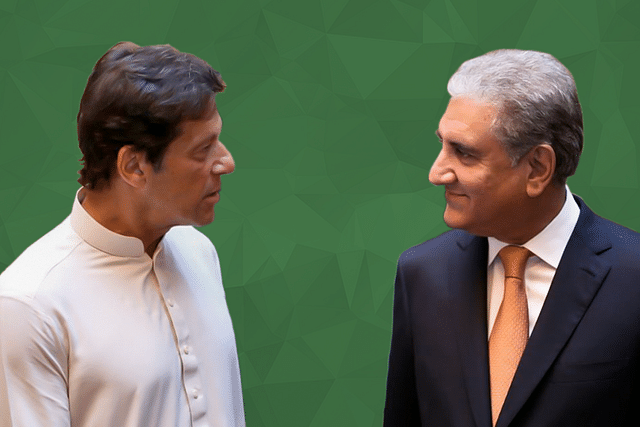

Although Pakistan is yet to reveal details, it’s being reported that the decision to take the issue to the ICJ was taken on the advise of British Barrister Ben Emmerson, who served as the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on Human Rights at the UN Human Rights Council between 2011 and 2017.

Pakistan’s Express Tribune reports that Emmerson has advised Prime Minister Imran Khan that Islamabad can sue India under the Genocide Convention.

Formally called the Convention on Prevention and Punishment of Crime of Genocide, this instrument of international law was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948. Both India and Pakistan are signatories to this convention.

Islamabad, it appears, is planning to use Article IX of the Genocide Convention, which gives the ICJ jurisdiction over such disputes.

However, this approach is riddled with hurdles.

Although Article IX of the Genocide Convention notes that a dispute can be brought to the ICJ at the request of any of the parties, there’s a catch.

India has put in place a reservation to Article IX, which states that the consent of all the parties will be required for the submission of any dispute to the ICJ. This, in simple terms, means India has ensured that no case against it under Article IX of the convention can be taken to the ICJ without its consent.

At the end of the 1971 war, after India captured over 93,000 Pakistani soldiers as Prisoners of War, Islamabad had instituted proceedings against India under the Genocide Convention. India had not participated in the case saying there was no legal basis for ICJ’s jurisdiction in the matter.

In 2006, when Congo brought a case against Rwanda under the same genocide convention, the court had ruled that it did not have jurisdiction to deal with the dispute due to the reservations put in place by the latter.

But, even if Pakistan manages to bring a case to the ICJ, hurdles would remain.

In 1974, India submitted a declaration to the ICJ accepting the jurisdiction of the court (under Article 36 (2) of the Statute of the Court) over all disputes other than those with a country member of the Commonwealth of Nations. Pakistan is part of the Commonwealth. Therefore, the court does not have jurisdiction.

India’s reservation were considered by the court when it decided on Islamabad’s case against New Delhi for the shooting down of its Atlantique aircraft by a MiG-21 fighter of the Indian Air Force over the Rann of Kutch in 1999.

Giving its decision in the case, the international court had refused to accept Pakistan’s argument that India’s Commonwealth reservation was extra statutory and obsolete, saying it was bound to apply the declaration.

Pakistan’s case seeking reparations and compensation was shot down.

Some may wonder how the ICJ took up the Kulbhushan Jadhav case. It did so because the Optional Protocol to the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR), to which both Islamabad and New Delhi are signatories, give it jurisdiction on disputes over interpretation or application of the VCCR.

Pakistan will also have to fight an uphill battle to prove that India has committed a genocide in Kashmir because, of course, it hasn’t.

The definition of genocide in Article II of the convention is very clear: only acts like ‘killing’, ‘causing serious bodily or mental harm’, ‘ physical destruction’, ‘preventing births’ and ‘forcibly transferring children’ with intent to ‘destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethical, racial or religious group’ qualify as genocide.

However, Pakistan, at best, may only be able to prove allegations of human rights violations against India using reports from 'independent' outfits such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, and the one prepared by the Office of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein in 2018.

But human rights violations would not qualify as genocide under this definition. Not to mention that many reports on the human rights situation in Kashmir are also critical of Pakistan for its violations in the parts under its occupation.

The cost (for Imran Khan’s and the Pakistan Army’s domestic politics) of failing to prove that India committed a genocide in Kashmir outweighs by a large margin the benefits for Islamabad of keeping the issue in international headlines.

Therefore, any attempt to move the ICJ using the genocide convention route is bound to fail and may leave Pakistan embarrassed.

But Islamabad believes it has one more option.

Prime Minister Khan has said that the country will try to move the ICJ 'through' the UN Security Council. This means Pakistan may be looking at using ICJ’s advisory role.

The ICJ can give its opinion on legal questions related to disputes when requested by organs and specialised agencies of the UN or other authorised organisations, says Article 96 of the charter of the UN.

In Pakistan’s calculation, this move will not just take the Kashmir issue to the ICJ (technically), but also help in ‘internationalising’ the conflict.

Attractive it is, but this option too would not be easy to exercise.

Given that India enjoys support from France, the US and Russia, three permanent members, such a move will be decisively thwarted.