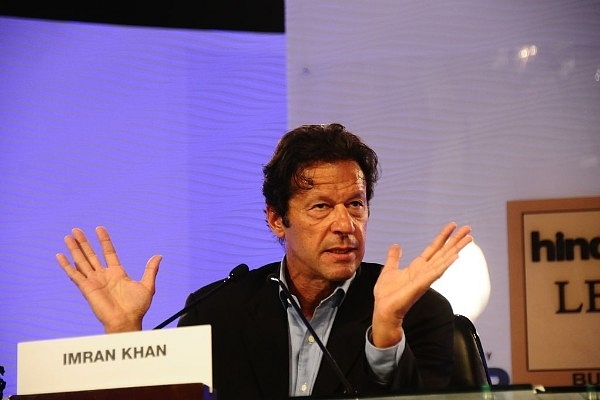

Imran Khan’s Over-enthusiasm Killed Potential For Improvement In India-Pakistan Relations

Imran Khan appears to have thought, mistakenly, that his arrival on the big stage itself would be enough to start mending India-Pakistan relations.

There is much work to be done on Pakistan’s side actually, and the approach needs to account for Indian sensitivities.

From India’s point of view, we need to start telling the Indian story to the world a little more effectively and a little more loudly.

Anyone who has even a semblance of understanding of India-Pakistan relations will agree that in this relationship there are simply no binaries; it’s not an either-or approach that can work. It’s important to understand that in this case grey is the dominant colour. Those who can work through this understanding in different situations can succeed in turning them around with a certain degree of hope.

Let’s apply this to Imran Khan’s situation. Given the immediate background from which he rose to become a prime minister-hopeful, it should have been obvious to him that his acceptance in India would have been fairly doubtful. He imagined, however, that his previous avatar as an educated and perceived liberal, projected during his playboy days, would return immediately to change that perception. Given India’s long suffering at the hands of Pakistan’s radicals and deep state, that was not going to happen. Newly elected leaders do try and espouse peace with neighbours, especially with those with whom their nation has been at odds. However, that is done to make a good beginning and not to establish the agenda on the first day.

Take the case of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. He invited all South Asian leaders for his inauguration to create the right environment, but he did not jump into proposals for talks on day one. In fact, he waited almost 18 months studying the environment and then took steps for progress; of course, these came to naught because of the intransigence of Pakistan’s deep state.

What could Khan have done? Instead of a transformational, all-ends-up approach, he should have tried the creeping and calibrated one: testing waters and moving beyond, never fully closing the windows but opening new ones, perhaps only half-way, to get a view. He should have realised the sensitivities involved.

First, that he was not considered in India to be his own man, having taken a ride atop a campaign perceived to have the total support of the Pakistan Army. It was obvious that he was not in charge yet, and any proposals or gestures would not necessarily have the backing of the all-powerful army.

Second, that to draw any interest from India, he would have to offer something different. India’s sensitivity is captured in the often-repeated and well-understood notion that “talks and terror cannot go hand in hand”. With the national election due in less than eight months, any move by the Indian government to accept a proposal would have to have been based on something that would give it a sense of achievement – of having a Pakistan talking differently. The clichéd idea of simply proposing talks without an accompanying change in approach would obviously not work.

Unfortunately, Khan thought that his arrival on the scene would itself augur well for a changed Indian response. Perhaps he did not realise that he had been watched very carefully in the run up to the election. His links with the army and the radical elements appeared much more embedded in his persona, which overpowered any liberal inclinations he may have carried in the past. The cricket fan following in India from back in the day was diluted after an awkward political ideology got linked to his name. Perceptions on this aspect would not change very quickly; more ground work would be required to establish credibility so as to undertake initiatives in as complex an issue as India-Pakistan relations.

Khan drafted the services of Shah Mahmood Qureshi as his foreign minister. Qureshi is not inexperienced and no greenhorn. The current strategy that Pakistan is following appears to be his brainchild. He does know that there is a fair percentage among the elite in India who prefer to look positively towards talks, irrespective of any dilution by Pakistan in its stand on terror. In the environment in which Pakistan finds itself, having to prove to the international community that it is doing something more than just the ordinary to curb terror – and its financing, in particular – it’s always advantageous to make a few gestures of peace without any serious outcome in mind. It makes for good optics for the international community and with the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) session underway, it will be spoken about quite positively in the corridors of the UN.

It is smart thinking. Qureshi knows that after India reversed its decision on External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj meeting him at the sidelines of the UNGA, all he has to do for some time is to maintain a disposition of innocence – that Pakistan’s new government had made a magnanimous offer to India, which India initially accepted but turned down within 24 hours. The Pakistan story will be told and retold all over the corridors there because Pakistan is adept at doing it. It won’t be said that even as the proposal for talks was being made there was action afoot by Pakistan Rangers at the Jammu IB to target a BSF jawan and a vicious campaign to target Kashmiri police personnel and their families. That is the Indian narrative and it won’t be spoken much. That Pakistan has taken no action to curb its support for terror by proxy against India won’t be spoken either. All that the world will hear is that India refused a magnanimous gesture by Pakistan’s new leader, who is attempting to give peace a chance.

If Qureshi is sincere, he will advise his Prime Minister that the coming eight-month period in the run up to the Indian general election is the time to create the right environment. During this period, internal deliberations with the Pakistan army chief must be carried out. General Qamar Bajwa is projected to be serious about seeking peace with India. If that is their common aim, they must remember that no Indian government can afford to even look in the direction of talks while continuing to be struck by terror. A groundswell of public opinion just won’t allow it.

So, it is Pakistan that has to demonstrate change, not India. Given the aftermath of the Wuhan summit and the very perceptible reset in relations between India and China, Pakistan, too, needs to look inwards and review the benefits of following its policy of fighting a proxy war. To remain in denial is not going to be helpful.

On India’s part, we may have been hasty in accepting the meeting at New York between the foreign ministers, but it is when work is in progress that such mistakes are made. What we really need to do is to start telling the Indian story to the world a little more effectively and a little more loudly.