Indo-Pacific And India: Mapping It Right

To spruce up the collective and cooperative security architecture in the Indo-Pacific, countries will have to re-assess threats across the wider region.

As India inches closer to the Lok Sabha polls, the country’s strategic community looks back at the last five years when India finally started building a largely pro-active foreign policy that takes into account evolving geopolitical realities and the country’s increasing material prowess. Nowhere has this been more apparent than in India’s re-energised attempts to reach out to South East Asia, countries along the Indian Ocean littoral and the Pacific Island nations.

Recent years have also attracted much excitement and speculation over the rebirth of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or the Quad — the coalition of India, Japan, the US and Australia invested in maintaining a “free, open, prosperous and inclusive Indo-Pacific”. The ‘Indo-Pacific’ itself — as a strategic construct that stresses on the interconnectivity and economic vitality of the Indian and the Pacific oceans — has become central to discussions around the maintenance of the rules that have shaped the international liberal order, which is at risk of alteration with the ascent of China.

The construct itself has Indo-Japanese roots, and the vital shift in strategic nomenclature from ‘Asia-Pacific’ to ‘Indo-Pacific' signals heightened expectations that New Delhi’s increasing abilities will significantly shape the geopolitical landscape of the region. But even then India is seen to have responded warily to the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) Strategy pushed by Japan and US. Hedging its bets against China, and trying to ‘multi-align’ across the board in the Indo-Pacific to the detriment of a long term geo-strategic plan, India is seen as “the weakest link the Quad”.

India continues to keep Australia out of the annual Malabar exercises in order to avoid giving China the impression that it is a de-facto Quad naval exercise. New Delhi has fallen short of criticising Beijing flouting the rules in the region as observed in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Shangri La address, where he spoke favourably of India’s cooperative relationship with China and Russia in the same breath as he made references to India’s partnership with US, Australia, Japan and the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN).

As pointed out in the recent articles that I co-authored with Asian geopolitics expert, Dr John Hemmings, some of the blame lies at home. India’s foreign policy and national security apparatus is highly bureaucratised, risk-averse, fragmented and continues to be deeply affected by Nehruvian hesitance vis-a-vis power projection. But a major reason for India’s restrained Indo-Pacific positioning is that its understanding of the Indo-Pacific does not exactly match that of the other major stakeholders in the region. Partner countries, particularly the US, will have to lend a more attentive ear to India if the Indo-Pacific has to evolve into a successful mechanism that preserves the rules of the game.

Where Does The Indo-Pacific Lie — And According To Whom?

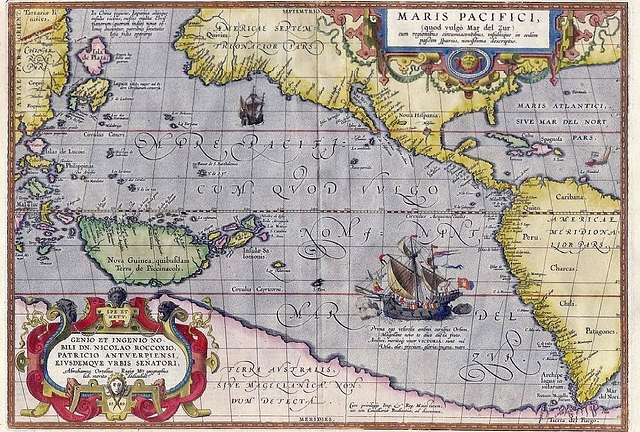

The geographical positioning of the Quad reveals the primary core of the Indo-Pacific. Great significance is assigned in the political imagination of policymakers to the geopolitical changes taking shape within the quadrilateral — covering much of the Pacific Ocean; North, East and South East Asia; and the eastern Indian Ocean. This also closely resembles the US’s geographical definition of the Indo-Pacific, which cuts the Indian Ocean into two halves, covering only the eastern half.

ASEAN, which occupies a geographically central position in these conceptions of the Indo-Pacific, has often iterated that the Indo-Pacific vision must support its primacy. ASEAN has also started occupying increasing importance in the articulations of the Indo-Pacific strategy of other states, most notably Japan, India and Australia, but increasingly also the US. This has kept the Indo-Pacific geographically confined, with South East Asia at its core.

Western Indian Ocean has not drawn the same kind of attention in these geographical imaginations of the Indo-Pacific, and that might explain India’s less-than-enthusiastic Indo-Pacific posturing.

India’s Understanding Of The Indo-Pacific

According to Gurpreet Khurana, the maritime strategist credited for coining the term, Indo-Pacific, Modi’s revitalised Look East Policy provided a ‘policy ballast’ to the Indo-Pacific concept. India has been alleviating its strategic partnerships and defence ties with countries such as Vietnam and Singapore. Going further eastwards, the Indian Navy has in recent years started participating in the USN Pacific Fleet-hosted RIMPAC exercises.

But while policies designed to further India’s engagements in this region (encompassing much of South East Asia, and the Pacific) might be the ‘cornerstone’ of New Delhi’s understanding of the larger strategic construct, this part of the Indo-Pacific, as outlined in India’s maritime security strategy only forms the secondary area of India’s interests. This despite the region housing some of its major export partners, a sizeable population of its diaspora and numerous maritime investment projects including offshore oil exploration investments in Indonesia, East Timor and the disputed waters of the South China Sea.

With increased militarisation of sea lanes that are of vital economic significance to India, a country whose trade with ASEAN, Oceania, North East Asia, and North and Latin America is experiencing significant growth, the region is likely to assume greater importance for New Delhi in the future.

However, given energy-hungry India’s continued reliance on crude oil, which feeds its growth and forms approximately 30 per cent of its total energy consumption, this region — for now is unlikely to replace the western part of the Indo-Pacific in terms of relative importance. In 2017, of the 222 million tonnes of crude oil India consumed, 211 million tonnes was imported largely from GCC and Western Asia. This region, covering the Arabian Sea, Persian Gulf, Gulf of Aden and south-western Indian Ocean is important as home to several important sea routes and choke points including the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, Bab-el-Mandeb connecting the Gulf of Aden to the Red Sea, and the Mozambique Channel and Cape of Good Hope along the African coast.

A large proportion of India’s trade, including the oil imports and trade with India’s major European trading partners pass through these strategically important points. The situation only worsens with parallel China-driven militarisation in the Indian Ocean: China’s claim that Djibouti (which connects the important sea lanes in the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean) is essential to its anti-piracy operations, has attracted the suspicion of India. Speculations about the true intentions behind Chinese investment in the Gwadar port, which lies close to oil-trade carrying Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf have turned into well-established recognition of military aspects of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The CPEC lies at the core of the China-Pakistan axis and is believed to have its roots in the shared desire to contain India.

To deal with this challenge, India has been rebuilding its primacy in the region through multilateral participation in the Indian Ocean Rim Association and through the ‘Mausam’ project aimed at reviving ancient maritime linkages with the littoral states. India has also been trying to establish a formidable maritime presence across strategic sea routes in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). There have been reports of India acquiring rights to build, or share naval facilities in Madagascar, Seychelles, Mauritius, and Oman.

India has also been making inroads into Africa. Through bilateral cooperation with Tokyo, New Delhi has been investing in capacity-enhancement, developmental and connectivity projects to offer a ‘benevolent alternative’ to China’s presence in Africa. But there are problems ranging from domestic pressures in countries that see themselves as being made pawns in the geopolitical competition to the sheer scale of Chinese presence in the IOR, which is difficult to match. India’s project in the Strait of Hormuz, the long-awaited Chabahar Port (a part of which is now being operated by New Delhi) has often found itself caught in the storm between Tehran and Washington.

Threats and interests in this region extend beyond securing routes for unimpeded trade. Freedom of navigation in this region is vital to India, which has 12 million members of its diaspora scattered along the western Indo-Pacific. Indian Navy, which has carried out HADR operations in Yemen, Lebanon, Libya and Kuwait would require unhindered movement across the maritime space in this conflict-prone region. Threats relating to maritime terrorism, also accommodated in the Indo-Pacific thinking in US and Japan, is rife in this IOR — the Mumbai attack in 2008 saw terrorism arrive at India’s shore by sea.

Although Japan has a geographically expansive understanding of the Indo-Pacific, which it sees stretching to the African Coast, India’s other like-minded partners in the Indo-Pacific need to pay greater attention to the western half of the Indian Ocean and its littoral for the construct to be successful in the preservation of the rules-based international system. Maritime cooperation in the IOR could take shape as increasing interoperability, situational strategic awareness, and maritime domain awareness, and would be useful in enhancing preparedness and presence in the region.

Indian Navy’s cooperation with the United States has been particularly lacking in the western IOR. The US’s Naval base in Diego Garcia in Central Indian Ocean has been argued to have the potential to be key to the US maritime India cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. The US military commands that cover the part of Indo-Pacific of primary importance to India, come under African and Central Commands, none of which have the preservation of the Rules Based Order as their operational priority.

The Central Command, in fact, has a close relationship with Islamabad, a key adversary of India, and a close Chinese ally. India’s partners will also need to understand the importance of Chabahar in bringing landlocked Afghanistan, and Central Asia, where there is an increased Chinese presence, and mounting BRI-driven debts to the Indo-Pacific.

For the collective and cooperative security architecture in the Indo-Pacific to become robust, countries will have to re-assess threats across the wider region.