When It Comes To Nepal, India Has No Option But To Treat It With Kid Gloves

India should not react too aggressively to the Nepalese provocations.

It won’t help.

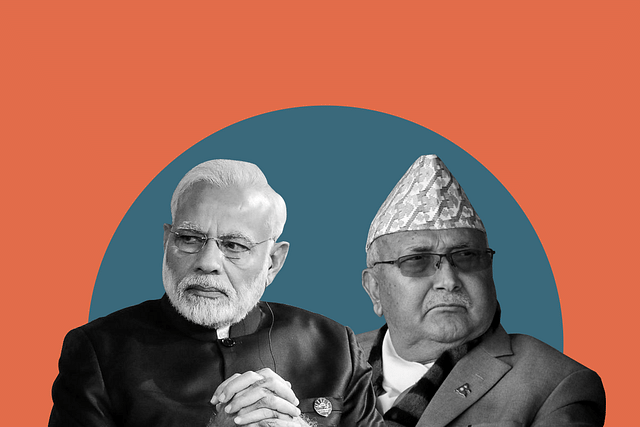

Nepal seems to have it in for India. A few days ago, it sprang a surprise by making territorial claims on the border of Uttarakhand and north-western Nepal. Next, Prime Minister K P Sharma Oli made a provocative statement, telling his Parliament that the “Indian virus (Covid-19) looks more lethal than Chinese and Italian now. More are getting infected.”

While India will surely be miffed that a country that has long cultural and economic links to us should be talking in this fashion, our reaction should be to play it cool. On the second accusation, at least, there could be some truth to it, despite the insensitivity with which it was made by Oli.

Thanks to India’s open borders with Nepal, the free movement of people both ways makes it easy for the virus to travel from India to Nepal – and vice-versa.

It is less likely to come from China and Italy, since movement from those directions follows normal travel screenings. The virus is a threat precisely because India and Nepal are closely linked by many ties.

India cannot afford to let its relationship with Nepal slide on the boundary issue, even if it is not something on which we can let that country dictate terms. Reason: Nepal is a Hindu country, and the last thing we need is a country with civilisational links to decamp to the Chinese or Abrahamic camps. That would be a disaster.

We need to understand two things about Nepal’s mindset.

First, a small country will always feel threatened by a larger country, especially if civilisational links make it easier for the larger country to claim cultural hegemonic status.

Seen through Nepalese lenses, culturally dissimilar Chinese, now coming with lots of lucre to seal the relationship, seems less of a threat to Nepal than the civilisational state to its south, with huge claims to a common culture. Nepal fears that it will get swallowed by India’s civilisational size, even though India has no territorial or hegemonic claims on Nepal.

In fact, China also is wary of India’s civilisational status. Reason: there is no other living civilisation in the world with the same 5,000-year continuous history and heritage as India.

India’s economy may be puny when compared to China, but civilisational claims are different. A large part of China’s Buddhist heritage is tied to India, even though the Chinese have their own philosophical heritage in Confucianism, Taoism, etc.

The difference between China and Nepal is this: China is a global thug and bully, the latter is merely fearful of India. The former needs to be challenged and countered, the latter needs to be reassured of our intentions.

Second, the maps and territorial claims need more diplomatic handling, including the setting up a working group between the two countries, so that a sensible solution can be reached.

The India-Nepal territorial flare-up had its origin last year, when India published new maps to account for the creation of two Union Territories in Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. This riled not only Pakistan, but also China, and so it is not unlikely that China asked Nepal to start escalating its own territorial issues with India.

In the new Indian maps, Limpiyadhura, Lipulekh and Kalapani areas are shown inside Indian territory, and the Nepalese effort at new map-making puts these in its territory. The area is strategically important for India, since it is close to the Nepal-China-India tri-junction.

Part of the problem relates to the shifting course of the Mahakali river, as happens sometimes with rivers. The differences relate to where the river originates.

During the East India Company era, the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816 put the river as the western boundary with Nepal, but subsequent British maps “showed the source tributary at different places”, notes Shyam Saran, a former foreign secretary and Indian ambassador to Nepal during 2002-2004, who wrote about it in The Indian Express.

Given the fact that Nepalese politicians have a chip on their shoulders about India, it becomes important for them to periodically show that they are capable of standing up to India.

Often, this show of defiance is meant for local consumption, and not intended to push the relationship to the edge of a precipice.

Nepal can’t really afford to do that as nearly 6-8 million Nepalese work in India – as they are allowed to under the Indo-Nepal Friendship Treaty. Nepali Gorkhas also serve in the Indian Army, and have fought on our side in almost every war since 1947.

The Nepalese claim that the friendship treaty is unequal, but have shown no great alacrity to actually renegotiate it, since equality means Nepal giving up its present privileges. But they do like to make a show of defiance.

It is worth noting that India-Nepal boundary disputes have been resolved to the extent of over 95 per cent, and the balance can be resolved, including the one now being raked up in the Kalapani area.

The solutions might be a reassurance and the constitution of a joint group to resolve the issue. The chances are the Nepalese will pipe down soon enough.

It is said that good fences make for good neighbours. Nepal’s problem is that the absence of a formal fence makes it feel vulnerable to India’s size and scale. Maybe, this is what needs to be done. We could erect some checkpoints at major areas of entry and exit, but work permits can be issued to Nepalese citizens so that actual movement for work is not impeded.

Fences, work permits and a working group to resolve cartographic differences should be the way forward. And yes, India should not react too aggressively to the Nepalese provocations. It won’t help.