Defence

‘Yes, We Can’ — This Indian Aerospace Startup Is On A Mission to Build India's Own Jet Engine

Karan Kamble

Mar 10, 2024, 12:38 PM | Updated Mar 11, 2024, 05:05 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The spirit of "Make-in-India" and "Aatmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India)," principally propounded by the Narendra Modi government over its two terms in power, has permeated nearly every sector in India.

The defence sector is no exception, and so it is for a small, but significant segment of this critical space — jet engines.

As India strengthens its air power, producing and procuring aircraft to bolster its defences, it is also exploring jet engine deals with foreign partners. It is doing so in search of as full a transfer of technical know-how associated with jet-engine building as possible.

India is discussing with France, for instance, to materialise an engine for India's fifth-generation fighter jet, dubbed the advanced medium-combat aircraft, currently under development. The two countries are looking at 100 per cent transfer of technology.

India and the United States (US) are similarly exploring the development of fighter jet engines for the Indian Air Force (IAF) through a partnership between Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) and GE Aerospace. India’s HAL will make F-414 engines in-house to power the IAF's light combat aircraft (LCA) Tejas Mark 2 (Mk2) as part of the collaboration.

The US-India deal will see 80 per cent technology transfer to India, including critical technologies, enabling "greater transfer of US jet engine technology than ever before," as US President Joe Biden has said himself.

While such international partnerships involving unprecedented technology transfer are in the offing, there has already been a small yet significant domestic effort over many years to build jet engines in India.

Most notable are the efforts of the Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE), a lab of India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO).

GTRE has been working on the development of the Kaveri engine, intended to power India's indigenously developed combat aircraft, such as the Tejas. While the project has faced challenges and delays, the lab made significant progress in improving the engine's performance and reliability.

GTRE has also been working on the development of small turbofan engines for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and target drones. These engines are designed to be lightweight, fuel-efficient, and cost-effective.

There has been little else in terms of jet-engine initiatives in India. The domestic manufacturing capabilities necessary to make jet engines have been limited, and so has it been with technology transfer opportunities. Even the high cost of research and development (R&D) in this space has acted as a deterrent.

However, despite such headwinds, one private effort to develop jet engines is making significant strides. The initiative has been flying under the radar, and deserves a closer look —

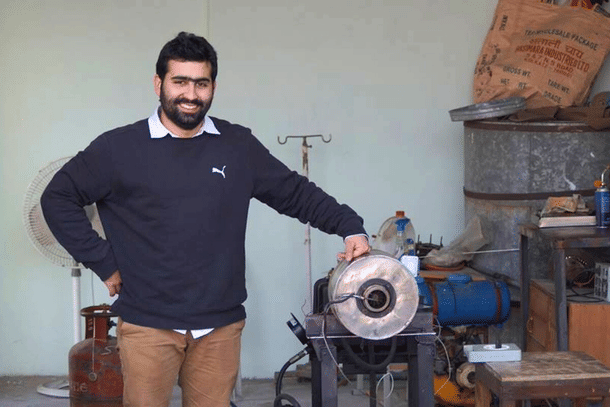

Prateek Dhawan heads DG Propulsion, a company that creates aerospace products, specialising in a powerful gas turbine engine for small aircraft and high-lift-power jetpacks. He wants to hand India its very own jet engine.

Making Engines As A Hobby

While still in college, studying Bachelor of Technology in Mechanical Engineering at the Dr BR Ambedkar National Institute of Technology in Jalandhar, Punjab, Dhawan was making homemade jet engines, confident that one day he would start a jet-engine manufacturing company.

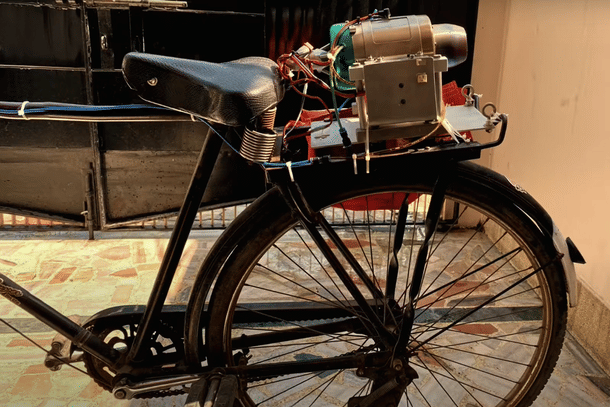

He integrated his hobby of making jet engines into his coursework, joined by classmates Anand Utsav Kapoor and Mahesh Kumar Mobiya. Together, they built a micro gas turbine, which Dhawan calls “the power generation counterparts of jet engines.”

The idea behind the project was to provide power for remote areas without a grid. They believed a micro gas turbine would work due to its high power-to-weight ratio.

The three budding engineers had based their turbine on the propulsion mechanism of a jet aircraft. The microturbine could operate on any fuel — liquid petroleum gas, kerosene, biogas, natural gas, diesel — and was capable of producing 25 KW of power and lighting up 25-30 houses of a village or an urban locality.

Kapoor, Mobiya, and Dhawan submitted their thesis and presented their project, titled “Design and Fabrication of a Micro Gas Turbine Using An Automotive Turbocharger for Distributed Power Generation,” in college in 2015, a year after graduation. He even made another engine to be housed in the engine lab of his college and stamped his phone number on it so like-minded people could reach out to him. (He has never heard back.)

This was Dhawan’s first engine — for which he, Kapoor, and Mobiya won a national award for engineering students. “It was a steep learning curve for me,” he tells Swarajya.

Encouraged by early successes and the engine's evolving performance, Dhawan’s work with engines, which began only as a hobby project, gained momentum. Such was his progress that, in 2015, a senior IAF officer expressed interest in his jet-engine work. For Dhawan, this contact validated the years of work he had put in by then.

That year, he moved to the US for a Master’s in Mechanical Engineering at Michigan Technological University. Over two years, he designed innovative concepts for which he filed four patents and received them over the last one year.

The technologies principally involved micro gas turbines and fuel cells. Potential applications for the innovations include hybrid electric vehicles, aircraft auxiliary power units, ships, military vehicles, and trains.

After graduating in 2017, he began working at top-of-the-line manufacturing companies like Caterpillar, John Deere, and Rolls-Royce, where he is presently employed.

From Lab To Market

In 2018, Dhawan tested his first aero engine. That year, when he was at John Deere, Dhawan met with a former Indian Navy personnel who shared his vision for developing jet engines and the related manufacturing ecosystem in India. Soon enough, Chirag Gupta came on board as a co-founder at DG Propulsion. The startup was formally incorporated a year later, in 2019.

Subsequent years were dedicated to fine-tuning the engine for optimal performance and size reduction, amidst several challenges stemming from India's limited jet-engine manufacturing ecosystem. They managed to develop and test their engines in-house entirely.

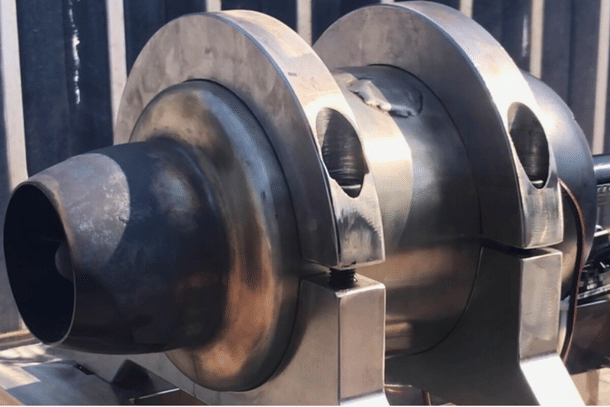

Today, DG Propulsion has three product offerings ready for the market. The DG J20, J40, and J60 turbojet engines are designed for UAV and defence purposes. The numbers 20, 40, and 60 in the engine names denote the maximum thrust capacity for those engines — 20 kilogram-force (kgf), 40 kgf, and 60 kgf. The J40 is said to be the most potent engine in DG’s current lineup.

The market opportunity for UAVs is huge within India as well as globally, estimated at $1 billion and $18 billion, respectively. The global market for small jet engines is valued at $1.3 billion. The demand for UAVs in the areas of defence, surveillance, and agriculture, among others, is rising.

Herein lies the opportunity for an aerospace and defence player like DG Propulsion. The company has tailored its jet engines for use in UAVs. These engines are fast, fuel efficient, affordable, and durable, just as UAVs like them.

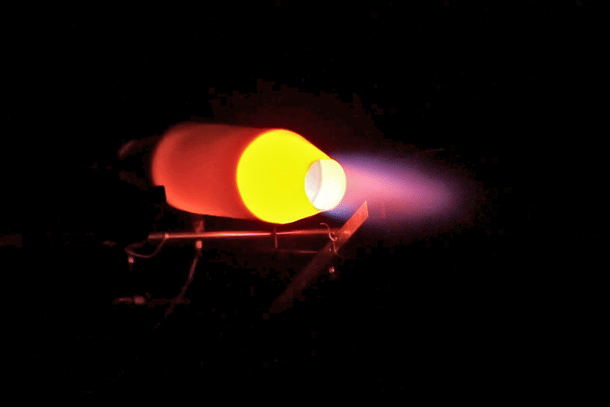

In February, DG Propulsion test-ran their engine, putting it through the ringer in the form of varying throttles and sudden RPM changes, among other things, first for 30 minutes and then for 1 hour and 10 minutes — crossing the elusive 1-hour mark for the first time. A 1-hour endurance run at about 90,000 rpm is enough to propel a UAV more than 300 kilometres (km).

More Than Just Engine Building

While Dhawan has been at engine-building for over a decade now, it is not his endgame. He says his work is also about instilling self-belief in Indian capabilities. “What we are trying to do at DG Propulsion, apart from building jet engines, is to build the narrative that, YES, we can build and test these engines in India,” he says.

The key technologies that go into jet engines, including the rotor, compressor diffuser, combustion chamber, and nozzle guide vanes, are all designed and manufactured by DG Propulsion in India.

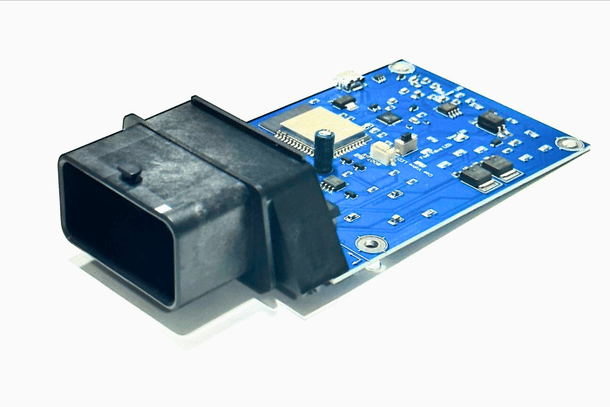

Even the controller, which monitors and manages the engine's operation — including parameters such as fuel flow, temperature, pressure, and speed, was designed and tested in-house. Remarkably, despite staying away from electronics all his life, Dhawan gave a good crack at it, learning printed circuit board design and code for a year and a half, to come up with a controller.

DG has gone through four iterations of their in-house controller. “Now this is not the best controller by a far margin, but it gets the job done quite nicely,” Dhawan revealed.

DG Propulsion is now eyeing sales of its jet engines both within India and across the South East Asia and Middle East regions. They also plan to offer post-sales services — maintenance, repair, overhaul — to their customers.

In the spirit of spreading the knowledge of jet-engine building, Dhawan and his team, which includes Tarandeep Singh as the director of manufacturing and Vansh Chopra as the assembly and testing lead, also plan to transmit their technical knowhow to the academia, principally to help train graduate students.

After receiving his first-ever funding only in early February 2024, Dhawan is calling for more “fuel” in the form of investments in order to “go full throttle,” forewarning that “it’s not gonna be an easy undertaking.”

He has made crowdsourcing appeals on social media, as well: “Do fund us as much as you can and we will deliver for our nation Bharat.” The financial support, he says, would go into “crucial testing and pushing the boundaries of indigenisation.”

His “mission — towards Atmanirbhar Bharat, towards self-reliant defense” is made up of two phases: designing a high-altitude drone powered by his engine, and “if the stars align… Gifting India its very own Jet Engine (full scale)” in phase two.

Fortunately for DG Propulsion, India appears committed to the manufacture of aero engines and gas turbines in India within five years.

It’s not been an easy journey for Dhawan and DG: for over a decade they have moved through “the toughest terrains of technology and engineering,” punctuated by “late nights, failed tests, and a awful whole lot of fuel,” but they are still here, alive and kicking.

If all of this effort means that they are able to give India's very own jet engine and show that jet engines can indeed be built in India, then it would all have been worth it.

Karan Kamble writes on science and technology. He occasionally wears the hat of a video anchor for Swarajya's online video programmes.