Economy

Leveraging The Demographic Dividend: The Case For India’s Challenge To China’s Economic Dominance

Vyas Nageswaran

Jul 16, 2024, 06:44 PM | Updated Jul 20, 2024, 01:29 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

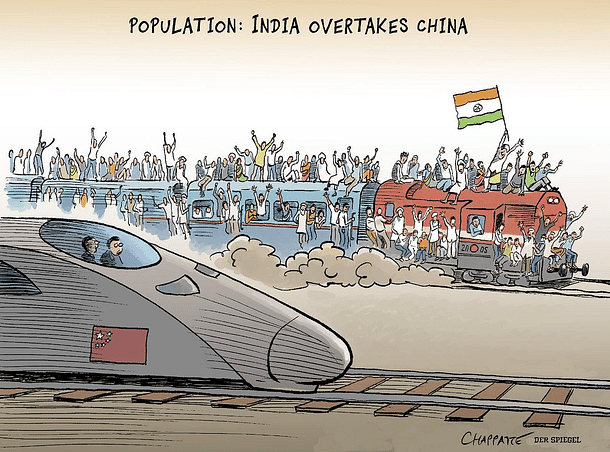

In April 2023, India overtook (mainland) China to become the most populous country in the world. Naturally, this significant demographic milestone invited responses from many commentators around the globe. A New York Times newsletter which covered the event was ambivalent as to whether this population change was a bane or a boon for the country, framed in the context of whether India will be able to surpass China to become the world’s leading economic power. The author raised certain pertinent points. In essence, they highlighted that whether or not India will be able to capitalize on its “demographic dividend” (a term that shall be explained later) and overtake China will depend on the country’s investments in infrastructure and education, and its ability to close “the gender-gap” where employment and educational attainment are concerned. A more extensive piece published by The New York Times elaborates on many of the concerns raised in the newsletter. Asking whether this will be “the Indian Century,” Alex Travelli and Weiyi Cai underscore that the answer to that question lies in the answers to a series of others: Will India be able generate sufficient formal employment opportunities? Can it get more women to participate in the labor force? Can it chart “its own path to prosperity” by overcoming systemic barriers to growth, such as encumbersome land and labor laws and “scanty spending on education and health”? These are all valid and important questions. Indeed, one must appreciate the balanced response to the question of India’s economic future and its demographic dividend. Other newspapers have certainly not been as dignified. Take, for example, the cartoon published by the German news company Der Spiegel in response to India’s population exceeding China’s:

Unsurprisingly, the cartoon drew the ire of many Indian government officials and political observers, not to mention Germany’s own ambassador to India who slammed it as “neither funny nor appropriate.”

Nonetheless, despite the reasonability of its questions and lack of overt racism, the points made by The New York Times are not particularly novel or counterintuitive. Obviously, whether the rise in India’s population and its demographic dividend are a bane or a boon for the country depends on a multitude of factors - a point that is not lost on the Indian government. Instead, where one should focus their attention is on what is being done by the government to unleash the potential that its population holds. It is my intention with this article to shed light on the policies and programmes that the Government of India is implementing to enable its demographic dividend to bear fruit.

Background: What is the Demographic Dividend and Does India Have It?

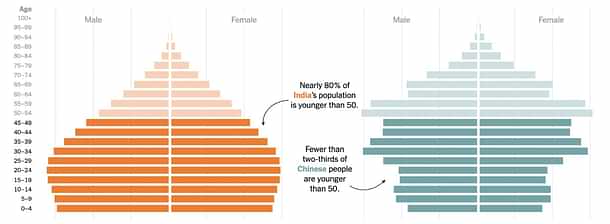

The term “demographic dividend” refers to the economic growth potential that a country enjoys when the proportion of its population that is within the “working-age” (typically those between the ages of 15 and 64) is significantly larger than the proportion of its population that is not. Prior to assuming the mantle of “world’s most populous country,” India already had this dividend; recent demographic trends have only increased the future size of it. Indeed, available population statistics confirm the existence of India’s demographic dividend, while simultaneously sounding the alarm over China’s population woes:

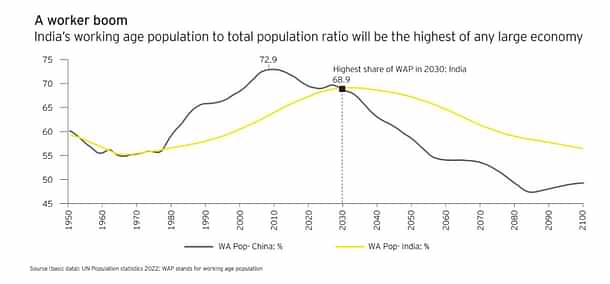

As can be seen from the chart, the percentage of the population that is younger than 50 is significantly higher in India than China. Further, more than 40% of India’s population is under 25, with an overall median age of just 28. In comparison, with a median age of approximately 39, not only is China’s population in decline but it is also aging. This, coupled with the fact that China’s working-age population has already peaked and is now on the downward trend while the ratio of India’s working-age population to total population is set to rise until 2030, reaching a high of 68.9%, provides a promising opportunity for India to not only catch-up with China economically, but surpass it.

Of-course, all this data merely points to the fact that there is a demographic dividend for India to leverage; how it will leverage it is an entirely different matter, which this article will delve into now. Specifically, two policy areas where improvement is essential (and already underway) for India to be able to capitalize on this demographic opportunity will be explored: infrastructure and education.

Infrastructure: Strengthening the Backbone of the Economy

Physical Infrastructure:

The Indian government clearly recognizes the indispensability of high-quality physical infrastructure when it comes to leveraging its demographic dividend. The Union Budget of 2023-24, introduced by Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in February of last year, reflects this recognition and commitment to developing physical infrastructure. The proportion of the budget set aside for this increased by 33% to US$122 billion. Additionally, the government also established the Infrastructure Finance Secretariat to facilitate private investment in the infrastructure sector including “railways, roads, urban infrastructure, and power.” Further, under the National Infrastructure Pipeline (a 5-year road map to improve infrastructure in the country), projects worth nearly USD 2 trillion are already being implemented and are at different stages of development, with the current project count exceeding 9,500 and covering over 50 sub-sectors.

One cannot speak of the government’s commitment to infrastructure without highlighting PM Gati Shakti - “the National Masterplan for Multimodal Connectivity.” In essence, PM Gati Shakti is a digital platform that brings together 16 government ministries, including the Ministry of Railways and the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways to integrate planning and coordinate implementation of infrastructure connectivity projects. Through this, the government hopes to enhance multimodal connectivity that will allow for the seamless movement of people, goods, and services from one place to another, which will in turn “help raise productivity, and accelerate economic growth and development.”

The initiatives highlighted in this section of the article barely scratch the surface regarding the efforts being made by the government to improve the country’s physical infrastructure. A significant package of other policy measures have also been implemented to this effect, such as the “continuation of the 50-year interest free loan to state governments for one more year to spur investment in infrastructure and to incentivize them for complementary policy actions, with a significantly enhanced outlay of US$ 16 billion.” The simple fact of the matter is that an unprecedented transformation is taking place in the infrastructure sector - a sentiment that will echo in subsequent parts of this article as well.

Digital Infrastructure:

To borrow a phrase from the Economic Survey 2022-23, “in keeping with the winds of change around the globe”, the government has placed significant emphasis on digitalization, taking its digital services to new heights in terms of “usability, interoperability, and accessibility.” Its efforts in the digitalization space began in 2015 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched Digital India - a program designed “to establish better connect between citizens and the government via e-services and deliver government services in a cost effective and transparent manner.” Since then, digitalization has radically transformed India’s economic landscape for the better.

A key example of a transformative initiative in this space is the introduction of the Unified Payment Interface (UPI) in 2016 by the National Payments Corporation of India. Simply put, UPI is a mobile application that allows users to access all their different bank accounts in one place, enabling seamless and rapid transactions between different financial institutions and peers. There are more than 350 banks and 250 million unique users on the platform, turning it into India’s largest digital payment network and the world’s fifth largest digital payment network by volume. The economic impact of UPI has been significant. It has promoted financial inclusion by bringing in a number of small business and unbanked individuals into the formal economy by providing them with a financial record and credit history, which also allows them to access credit more easily. Further, with UPI, businesses are now incentivized to innovate and develop e-commerce solutions that would enable them to reduce their overhead costs and expand their consumer base.

All in all, when one looks at the efforts and initiatives the government has undertaken in the infrastructure sector (both physical and digital), it is clear that there is a strong appreciation for the importance of investing in and developing this sector for the future of the country’s economy. Indeed, when it comes to the leveraging of India’s demographic dividend, these efforts will prove to be highly consequential by allowing for greater factor mobility, job creation, and productivity enhancement throughout the country. So long as infrastructure remains a priority and a collaborative spirit is maintained amongst the central government, state governments, and private entities, it is very likely that this sector will continue to play a vital role and contribute immensely to the reaping of the nation’s demographic dividend.

Education: Creating Agents of Change for the Economy

What good is having a car if you do not know how to drive? That is likely to be the argument put forth by those who view the government’s infrastructure investments in isolation and belabor the deficiencies in India’s education system. Again, however, I would argue that this is not a point that is lost on the government. Robust policies are being implemented to transform the country’s education sector, but, given that these reforms are structural, it will naturally take time (years, if not decades) for their full effects to be felt. With that being said, let us take a look at the cornerstone of the government’s efforts to revamp India’s education system: The National Education Policy (NEP) of 2020.

Predicated on an understanding of the indispensability of “providing universal access to quality education” and developing “foundational capacities” as well as “higher-order cognitive capacities,” the NEP aims to facilitate the continuation of India’s economic ascent and consolidate its ability to leverage its demographic dividend. To this effect, the policy calls for a replacement of the current 10 + 2 educational structure with a 5+ 3 + 3 + 4 model, covering ages 3-18, the reason being that under the current structure, children in the age group of 3-6 are not covered. Further, recognizing that strengthening foundational literacy and numeracy is essential for all “future schooling and lifelong learning,” the Ministry of Education has launched the National Initiative for Proficiency in Reading with Understanding and Numeracy (NIPUN Bharat). As part of the NIPUN Bharat mission, all State/UT governments are to “prepare an implementation plan for attaining universal foundational literacy and numeracy in all primary schools, identifying stage-wise targets and goals to be achieved by 2025, and closely tracking and monitoring progress of the same.”

Significant developments are taking place in the area of higher education as well. For instance, as part of the NEP, in January 2023, the University Grants Commission unveiled a draft legislation that would “facilitate entry and operation of overseas institutions in the country for the first time.” In keeping in line with the general spirit of the NEP, the motivation behind this legislation is to revamp the country’s heavily-regulated education sector and mitigate the issue of brain drain by allowing domestic students to receive the same quality of education they would get abroad. The policy is specifically meant to target top-tier universities, such as Yale, Oxford, and Stanford that Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been trying to entice to set up campuses in India.

As with the case of infrastructure, only a handful of the initiatives the government is undertaking to transform the education sector and deliver high-quality education to the country’s population have been covered in this article. Even a cursory glance of the NEP would reveal the tremendous amount of planning and consideration that has been given to this sector and how the government intends on transforming it to meet the educational needs of the country and prepare its students to thrive in the 21st century. Collectively, the investment and policies being rolled out in the education sector will allow India to develop its human capital effectively, such that its demographic dividend is not simply a lame duck but a competent, empowered, and knowledgeable workforce that will allow the country to realize its economic potential.

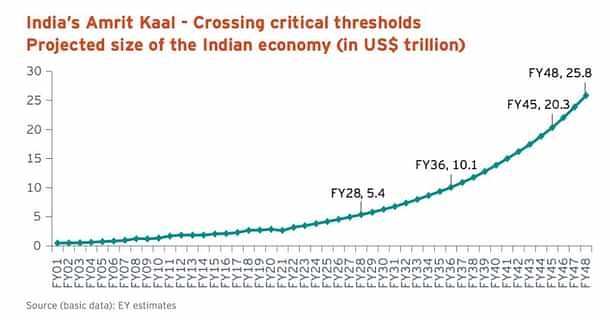

The Way Forward: India in Amrit Kaal

When presenting the Union Budget in February 2023 FM Sitharaman referred to it as the first budget in “Amrit Kaal,” the next 25 years of Indian independence. The term is a Vedic allusion, referring to a period of time in which “the gates of greater pleasure open for the inhuman, angels and human beings.” It is a powerful allusion, for it captures the sense of optimism, aspiration, and ambition that characterizes the spirit of many Indians today – a spirit that has not been shaped by lofty slogans or idealistic promises, but by tangible growth and development.

Of course, not everyone shares in this optimism. In December 2022, former Chief Economic Advisor (CEA) Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman published an article in Foreign Affairs titled “Why India Can’t Replace China,” in which they express great skepticism over India’s ability to attract foreign capital likely to flow out of China and lament the country’s subpar growth performance in the last few years. There are at least a couple of obvious flaws in their argument. The first is that India, just like every other country in the world, was forced to reckon with the ramifications of an unpredictable pandemic and trade disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine, explaining much of its “subpar” growth in the last three years (assuming that is even a fair descriptor). To use these anomalous shocks to paint a pessimistic picture of the country’s economic future only reflects an inability to see the woods for the trees. Further, many of the economic reforms being initiated by the government are structural, which means their effects will not manifest overnight. As the Sufi poet Rumi once said, “Patience is not sitting and waiting, it is foreseeing. It is looking at the thorn and seeing the rose, looking at the night and seeing the day.” It is through this lens that one must view India’s structural economic reforms, such as those being made in the infrastructure and education sector.

In direct response to Subramanian and Felman’s article, India’s current CEA, V. Anantha Nageswaran, and Indian Economic Services Officer Gurvinder Kaur published their own piece in Foreign Affairs titled “Don’t Bet Against India.” In addition to the counterarguments that I have mentioned above, they also note that many of Subramanian and Felman’s claims “do not stand up to empirical scrutiny.” Indeed, India has already succeeded in attracting capital away from China. For example, in an effort to reduce its dependence on China, Apple now manufactures 14% of its iPhones in India – a significant uptick for the country considering that only 1% of the world’s iPhones were produced there in 2021.

In sum, I hold the view that a compelling case can be made for India’s challenge to China’s economic dominance. It is abundantly clear from what has been presented in this article that the Government of India does not take its demographic dividend for granted and is busying itself with laying the groundwork for the country’s young and dynamic workforce to catapult the economy to new heights. I also cannot emphasize enough that the policies and programmes discussed in this article barely scratch the surface of what is happening in the country. That being said, at the risk of stating the obvious, I am no expert on policy matters or developmental economics. I do not possess the expertise to say with absolute confidence whether one should or should not bet against India. However, what I will say is that my research for this article has filled me with much optimism about the country’s future. Notwithstanding any major shocks, so long as current demographic trends for India and China continue to be what they are and economic development continues to remain a top priority for the Indian government, India could give China a serious run for its money. For those who would still prefer to back China’s horses, I just have one question to ask: what good is a car if there is no one to drive it?