Technology

Drone Hobbyist Turns ‘Make In India’ Manufacturer And Tells The Tale Of His Startup Adventure Ride

Karan Kamble

Apr 04, 2024, 10:53 AM | Updated 10:53 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

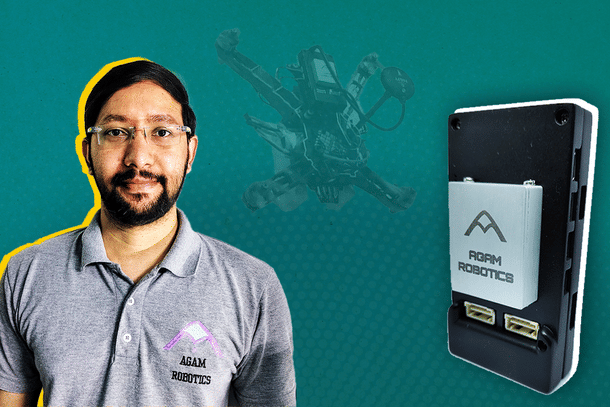

Karthik Rangarajan is a man on a mission: to deliver truly made-in-India drone components to customers.

Building from scratch over nearly three years of research and development (R&D) work, the robotics engineer’s one-man show, Agam Robotics, is now ready with the prototype for an essential part of a drone: its electronics.

In only a few months’ time, the locally made “autopilot” — a flight controller — will be on the market for integration into existing drone platforms. An autopilot is essentially a combination of electronics and software used to control the flight of an aircraft or drone.

A handful of Agam autopilot prototypes are currently in the hands of early customers, who are testing them out in a variety of ways. Meanwhile, Karthik is keeping his ears open for feedback, while working to scale up his offering in the months to come.

The drone sector in India is considered a “sunrise sector,” implying that it is in the early stages of its trajectory, brimming with potential, and on its way up towards rapid growth and innovation.

From defence to agriculture, healthcare to e-commerce, drones are likely to find use in nearly every sector in the future.

This is why the Government of India is pushing for drone manufacturing within the country. They announced a production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for the sector in September 2021 to promote the manufacturing of drones and drone components in India. The scheme was introduced to reward domestic value addition, encouraging local manufacturers to grow and, in the process, cut down on the country’s drone imports.

Presently, there are over 200 drone startups in India. The size of the country's drone market is $1,108.9 million, as of 2023. According to the market research firm IMARC Group’s projection, the market will reach $2,434.3 million by 2032, with a growth rate (CAGR) of 9.13 per cent during 2024-2032.

Stepping away from the macro view, however, we look at the journey — nay, an adventure — of a drone hobbyist who turned manufacturer out of love for these aerial robots.

Beginnings

Karthik’s love for drones goes back to his late teens. As an undergraduate student of telecommunications engineering in Bengaluru, he chose to build a drone as part of his mandatory final-year project — a familiar rite of passage for engineering students.

He sought to demonstrate the “VTOL” concept — vertical take-off and landing. It’s quite common now, not so back then. He and his team were working on developing the firmware, a type of software embedded into hardware devices like drones to control their operation, for it.

“Because of the lack of technology back then, we couldn’t completely make it an effective system. But we were able to accomplish the concept of a tilt-wing rotor, wherein it can take off like a drone and mid-air it can tilt the rotors and transform into an aircraft,” Karthik told Swarajya.

In 2013, he picked up the leftover drone parts from the project and began building more drones. During this time, he got actively involved in a club for drone enthusiasts where beginners were trained in piloting and controlling drones through visual contact. He was part of this club for three years, designing and developing radio-controlled aircraft models.

Coming from an electronics background, Karthik picked apart drones and saw with a curious eye how the various electronic components came together. In 2014, he landed a job at an electronics company that manufactured printed circuit boards (PCBs) for various sectors.

“I was working in the defence and aerospace sector, so that gave me an insight into how PCBs are manufactured. I got interested in how I can put those concepts into the drones side, how I can design and manufacture these (drones),” he says.

Realising the need to upskill in this space, Karthik decided to pursue a Master’s in robotics, an area of specialisation that would give him the necessary cross-disciplinary expertise he was seeking. He completed a Master of Science (MS) in robotics, mechatronics, and automation engineering from New York University.

All through this period, the idea of building a made-in-India drone remained seated at the back of his mind. In the pandemic year of 2020, while still in New York, Karthik initiated the R&D work necessary to make it happen. Admittedly, the “R” in “R&D” dominated efforts for a couple of years.

“I started working on the brain of the drone, the autopilot or the flight controller, which manages the entire system on the drone. That’s basically what makes the drone stay in the air, in its place,” he says.

The flight controller is a small electronic unit made up of sensors, processors, and software. It helps stabilise and control the drone's orientation, speed, and altitude.

Combining the sum total of his learning, acquired through years of educational and professional experience in electronics and robotics, Karthik began designing the flight controller. “I started developing the entire PCB schematics, and I started talking to people in the market in India who were working in the drone sectors… to see what are the problems they are facing.”

He also collaborated with the open-source community. “I told them I am working on this design, and they say they are also working on a very similar thing. And I started getting together with them when I was in the US, and during weekends or weekdays when I am back from office I would work on these designs and start making progress,” he tells this writer.

Karthik finalised the designs in 2022, two years after starting work. This was also when he was to return to India.

Back In India

With the design part of the process behind him, Karthik decided to move ahead with manufacturing in India. It would be his next big step in the product development phase.

Here is where things got more challenging. Finding manufacturers to execute his designs took longer than expected. “It took almost six to eight months to find the right manufacturers. Because in my case, the designs were slightly complicated. The complex designs are not easily manufactured in India,” the Agam Robotics founder tells Swarajya.

The manufacturers who had the capability to materialise these complex designs charged a premium. It led Karthik on a chase for the “sweet spot” between manufacturing and the cost of manufacturing.

He did identify the right manufacturer eventually. The first iteration of the design came through in February 2023. He then got going on “product development and testing of the actual firmware on the actual hardware.”

Over the next few months, he went through multiple iterations, encountering and resolving various issues with the components he had chosen to go with due to the global chip shortage.

Karthik changed several distributors until he found one who could provide him with satisfactory alternative industry-grade drone components. By January 2024, he had his drone units manufactured and working alright. “Right off the bat, once the components were in place and I loaded the programme, the firmware, it was all working fine,” he says.

Testing was accomplished by integrating the electronics into older drone platforms in Karthik’s possession; he had accumulated quite a few of them over the years. The various drone parts he had were off the shelf and made in China. But he knew they worked, making it possible for him to swap out and test the flight controller alone.

“I replaced the existing autopilot with my autopilot into the system and flew it (for) 100+ hours. We did a lot of testing,” he says. He flew the test drone in many different places and incorporated many different subsystems to check for compatibility. Even the open-source community tested the drone extensively.

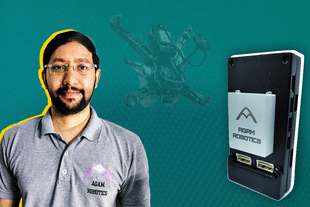

His made-in-India drone component was finally ready for deployment. But he didn’t want to ship just the electronics. It still didn’t wear the look of a finished product, according to Karthik. The addition of vacuum casting and an aluminium casing, chiselled through CNC machining, to the flight controller did the trick.

In February this year, a handful of units were shipped to customers in the first-ever batch of Agam's autopilot, a term Karthik prefers over “flight controller.”

“I tend not to call it a flight controller. I call it autopilot because this kind of system, the autopilots, can do a lot of other vehicles, not just drones. It can do airplanes, monocopters, rovers, underwater vehicles, underground vehicles, and so on.”

One of the customers in possession of the Agam autopilot is already testing it out in the Himalayas. The feedback is invaluable for Karthik, who is keen to improve his product.

“They said if anything happens, we will be happy to assist. We will be able to get logs or details of how it performed and whether it can withstand that cold temperature or not — all those things we can get to know from them. So that is something I am waiting for.” He is likely to learn of the outcome in the early part of April.

Regular testing of prototypes will pave the way for the autopilot system to be used in drones serving commercial applications, such as agriculture or defence.

Agam’s Different

What stands out about Agam’s autopilot is that it is truly ‘made in India’ to the extent that it can be, unlike many other similar drone systems available on the market.

“If you see most of the companies (except in defence), they are getting these autopilots from China and they are getting all the different parts of the drone, and putting that together into a drone. That’s the assembly side of the drone, not the individual subsystems,” Karthik says.

The rider “to the extent that it can be” comes from the fact that India is still in the process of building up its semiconductor industry.

“If you consider the electronic components, that’s a whole new story. The semiconductor industry is non-existent in India, as of now. We don’t have any alternative component manufacturers in India. As a startup, we cannot do anything,” says Karthik, who had to import the components and assemble them here in India.

Yet, his case is very different from what is typically claimed as made in India: “What majority of the other companies are doing is, they do the manufacturing of the PCB itself in China, or any other place outside of India, and then they bring the board here and put screws, nuts, and bolts together and they call it ‘made in India’.”

“That is where we want to differentiate ourselves: we are manufacturing all the PCBs here in India,” he adds.

Agam Robotics is currently outsourcing the manufacturing process due to the lack of necessary capital, but the manufacturing takes place within the country.

Unlike the other players in the market, Karthik has based his autopilot on the Pixhawk Autopilot Bus, the industry standard for drones. In fact, his autopilot is the first-ever Pixhawk flight controller to have a non-STM32 chip.

While the STM32 from STMicroelectronics is commonly used in flight controllers, Karthik opted for the more powerful, latest MCU imxRT series from NXP Semiconductors. This choice gives the Agam autopilot V6X-RT more features and functionalities, and makes it future-proof.

Yet another differentiating factor for Agam is that they have made their autopilot keeping both industry players and regular consumers in mind. Otherwise far too much focus is directed at industrial use.

Karthik makes up all of Agam Robotics at present. He is, however, currently seeking a chief technology officer and co-founder for Agam. “If it happens, well and good. But my focus is more towards raising funds and hiring people so that I can delegate some of the work, because I can manage both the technical and non-technical side. I have been doing that for a while now.”

A team of engineers and technicians would help him scale up, he says.

Agam Robotics is well-poised to grow in the future. Indian companies that rely on imports from China, and struggle because of it due to the shipping costs, delays, and unavailability of service, among other things, might find it beneficial to switch to a domestic manufacturer.

“I have already spoken to a bunch of companies and they are super interested to get their hands on the product. I wish I had made a bigger quantity of prototype batches. I am working on getting the next pilot batch,” Karthik says.

Given the requests pouring in from different companies for customised solutions, Karthik is considering making three or four versions of the autopilot to cater to different sectors, like defence, industry, and the consumer.

Making the entire drone is not on the cards currently. Agam's focus at the moment is to develop multiple drone subsystems in addition to the autopilot. These subsystems will include navigation systems like the GPS module system, various sensor systems like the optical flow and distance sensors, battery management systems, motor controllers, and so on.

“We will provide an ecosystem; we will be able to provide all the parts required to build a drone,” Karthik says, adding that Agam will retain its focus on electronics rather than go into the mechanical aspects.

Karthik is buoyed by the order requests already coming in, including from South Korea, Europe, and the United States (US). Instead of building drone subsystems only after receiving orders, as tends to be the case, Karthik plans to build up an inventory of his products. His plan over the next few months is to scale up to thousands of autopilot units.

"In general, the entire drone has to be made in India. That's the whole goal, the whole vision of the company,” Karthik has said on his YouTube channel “Karthik Kwads,” where he documents his hardware startup journey regularly.

Going from prototyping to mass producing drone subsystems will be the big challenge for Karthik this year, but he is ready and raring to go.

Karan Kamble writes on science and technology. He occasionally wears the hat of a video anchor for Swarajya's online video programmes.