Technology

OneWeb-Eutelsat Merger Has Created A Powerful Global Service Provider In Space — With Strong Indian Presence

Anand Parthasarathy

Oct 12, 2023, 11:55 AM | Updated 11:54 AM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

The merger announced last month, between the Bharti Enterprises-led OneWeb, the global low earth orbit (LEO) satellite communication network and Eutelsat, the French operator of geostationary (GEO) communication satellites, has not received the attention it warrants in the Indian media.

This is one of the most interesting — and potentially far reaching — developments in the commercial sector of space technology.

Till now, there was a clear separation between two types of communication satellites harnessed for terrestrial communication services.

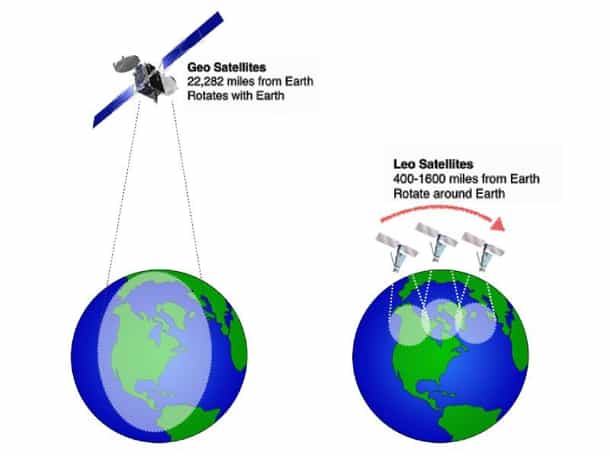

GEO Versus LEO

The long established and mature market harnessed geostationary or GEO satellite clusters which hover 36,000 km (22,282 miles) above the earth.

They match their speed with the earth’s rotation — about 11,300 kmph ( hence called geosynchronous) — and for this reason appear to occupy a fixed position in space.

This has definite advantages when such groups of such GEO satellites are used as platforms to provide global communication services: receiver antennas on earth can be fixed to point in one direction.

A small number of such satellites (in single digits) can cover most of the globe, except the polar regions.

This has enabled companies like Eutelsat to provide communication services for voice and data, both fixed and mobile, as well as the lucrative broadcast television services for tens of thousands of stations worldwide.

Operators like Iridium, Inmarsat, Thuraya and Globalstar offer satellite terminals and hand phones for global reception which is why they are favoured by explorers, disaster relief and policing agencies worldwide. In India, Inmarsat offers these services in partnership with BSNL.

Then came the new kid on the block — the LEO satellite which could be lofted into an orbit much closer — and hence a logistically simpler orbit — 600-2,500 km (400-1,600 miles) above the earth.

They travel at approximately 28,000 kmph and make 12 orbits of the earth per day. A single LEO satellite would be visible from any single point on earth for just a few minutes — hence to provide smooth and uninterrupted coverage you need to position hundreds of such satellites in a network.

LEO technology has been available since the 1980s, but it is only in recent years that companies are offering satellite communication and satellite-based Internet services harnessing LEO networks.

OneWeb has 634 satellites in position out of a planned 648. Recent comer Amazon, which also plans on offering services in India, has only just launched its first satellite.

And the Elon Musk-owned Starlink, which is already in operation since 2019, has 5,000 satellites functioning, offering services in 60 countries.

Significance Of Eutelsat-OneWeb Merger

The merged entity will be headquartered out of Paris. OneWeb will be a subsidiary operating commercially as Eutelsat-OneWeb, with its centre of operations remaining in London.

It will have Bharti Enterprises as its largest shareholder with 21.2 per cent share and Sunil Bharti Mittal will be the vice-president (co-chair).

And herein lies the significance: This is the world’s first GEO-LEO integrated satellite group, transforming space communications and addressing the fast-growing connectivity market.

Access to Eutelsat’s strong legacy business, serving over 7,000 TV stations and 1,100 radio stations, with its 36 GEO satellites coupled with the potential of OneWeb’s 648-satellite LEO constellation, gives the new group arguably the most advantageous position in the global commercial satellite services sector today.

And the fact that an Indian company, is in effect, the biggest owner within the group, says much for how far India has come on the international sat-com platform.

Strategically and commercially, the true potential for India of the Eutelsat-OneWeb combo is yet to be realised. But the advantage for national ambitions cannot be overstated.

Anand Parthasarathy is managing director at Online India Tech Pvt Ltd and a veteran IT journalist who has written about the Indian technology landscape for more than 15 years for The Hindu.